The singularity won't be gentle

If AI is even half as transformational as Silicon Valley assumes, politics will never be the same again.

There’s a recurring problem on the Silver Bulletin editorial calendar: I always have AI posts planned for some point in the near future, but rarely manage to publish them. There’s always a politics or sports thing that seems like a lighter lift.

We did publish what I thought were two good stories on AI last year: one in January entitled “It’s time to come to grips with AI” and another in May: “ChatGPT is shockingly bad at poker”. These were fair reflections on my mood regarding AI at the time, and I think both stories hold up well. But we haven’t written much on AI since then, even though it continues to occupy a large fraction of my mental bandwidth. There’s a tendency for everything that gets written about AI to fashion itself as being “epic”, but perhaps that’s exactly the wrong mindset given how rapidly the landscape is changing, and incrementalism is better. So I hope you’ll excuse this unplanned and slightly stream-of-consciousness take.

Recently, the trend in the circles I follow has been toward extreme bullishness on AI, particularly in its impact on programming and the possibility of recursive self-improvement (i.e., where AI models continually create better versions of themselves). This reflects a reversal from a stretch in late 2025 when progress seemed a little slower than smart people had been expecting. Admittedly, what constitutes “bullish” or “bearish” depends on whether you think more rapid progress in AI would be good for civilization or bad (even catastrophic). It’s also not clear the extent to which these changes in the mood reflect “vibe shifts” as opposed to actual developments on the ground. If you look at AI-related prediction markets1 — or for that matter, more traditional markets2 — they’ve gyrated around, but probably not as quickly as sentiment about AI has on Twitter or Substack has.

So here’s a take I consider relatively straightforward, but I don’t think has really sunk into the conventional wisdom. If AI has even a fraction of the impact that many people in Silicon Valley now expect on the fabric of work and daily life, it’s going to have profound and unpredictable political impacts.

Last June, Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, published a blog post entitled “The Gentle Singularity”. If you’re not familiar with the jargon, the Singularity (sometimes capitalized, sometimes not) is a hypothesized extremely rapid takeoff in technological progress — so technologies that would once have taken years or decades to come to fruition might be realized in months, days, hours, minutes, microseconds. I’m not sure that I want to weigh in right now on my “priors” about the Singularity. It’s probably safe to say they’re more skeptical than your average Berkeley-based machine-learning researcher but more credulous than your typical political takes artist.

What I’m more confident in asserting is that the notion of a gentle singularity is bullshit. When Altman writes something like this, I don’t buy it:

If history is any guide, we will figure out new things to do and new things to want, and assimilate new tools quickly (job change after the industrial revolution is a good recent example). Expectations will go up, but capabilities will go up equally quickly, and we’ll all get better stuff. We will build ever-more-wonderful things for each other. People have a long-term important and curious advantage over AI: we are hard-wired to care about other people and what they think and do, and we don’t care very much about machines.

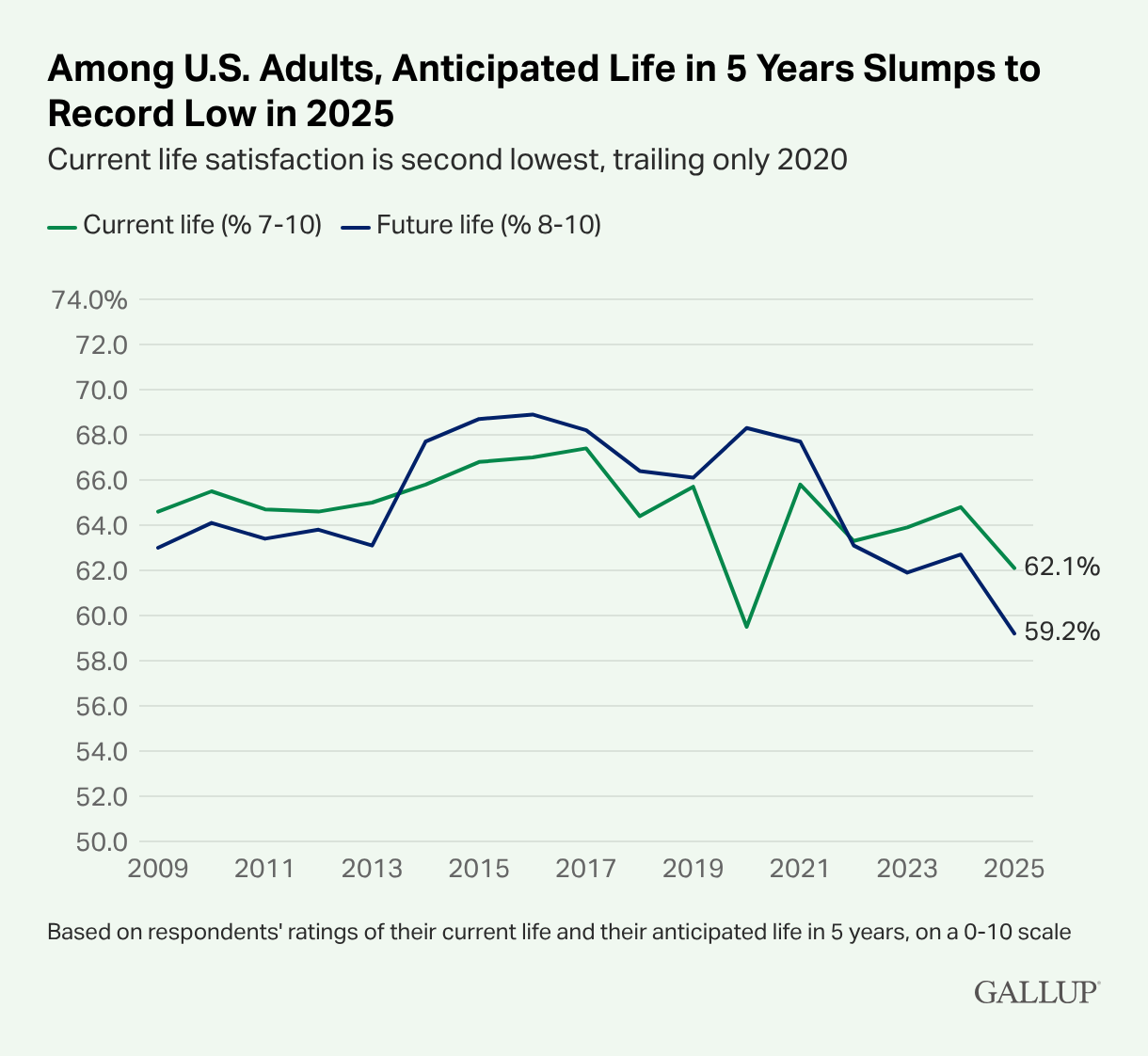

Although I doubt that AI per se is having a large impact on these measures right now, you’ve probably noticed that the broader public isn’t exactly in an optimistic mood. Certainly not in the United States, although we’re not unique in that regard. Gallup polling released this week found that optimism about future life satisfaction has plummeted. A lot of that is due to “politics”: the decline has been concentrated among Democrats since Trump was reelected, a sentiment that I empathize with but I don’t think is entirely justified.

Still, the belief that technological progress, warts and all, would be broadly beneficial for society, has come under some deserved scrutiny lately. In other Gallup polling, the percentage of people who have “a great deal” or a “large amount” of trust in “large technology companies” fell from 32 percent to 24 percent between 2020 (the first time Gallup posed this question) and last year.

I’ll admit to having my own anxieties about AI. Despite what you might assume, I probably rate lower than average on broader anxiety/neuroticism (especially as compared to other liberals). Even if AI “disrupts” jobs like mine, I’m probably in the upper percentiles of the population in my capacity to weather any such storms or plausibly to benefit from them.3 I do wonder, though, how I’d feel if I were a decade or two younger — or if I had children. (Perhaps, if AI progress is very rapid, I’ll go into a slightly-earlier-than-planned retirement and bide my time playing poker.4) I was recently speaking with the mom of an analytically-minded, gifted-and-talented student. In a world where her son’s employment prospects are highly questionable because of AI, even if he overachieves 99 percent of his class in a way that would once have all but guaranteed having a chance to live the American Dream, you had better believe that will have a profound political impact.

Let me add a few additional points on why I think the political impact of AI is probably understated:

“Silicon Valley” is bad at politics. If nothing else during Trump 2.0, I think we’ve learned that Silicon Valley doesn’t exactly have its finger on the pulse of the American public. It’s insular, it’s very, very, very, very rich — Elon Musk is now nearly a trillionaire! — and it plausibly stands to benefit from changes that would be undesirable to a large and relatively bipartisan fraction of the public. I expect it to play its hand in a way that any rich “degen” on a poker winning streak would: overconfidently and badly.

Cluelessness on the left about AI means the political blowback will be greater once it realizes the impact.5 My post last January was partly a critique of the political left. We have some extremely rich guys like Altman who claim that their technology will profoundly reshape society in ways that nobody was necessarily asking for. And also, conveniently enough, make them profoundly richer and more powerful! There probably ought to be a lot of intrinsic skepticism about this. But instead, the mood on the left tends toward dismissing large language models as hallucination-prone “chatbots”. I expect this to change at some point. And as Anthropic’s Jack Clark pointed out when I spoke with him for my book, this degree of profound technological change often produces literal revolutions:

So when Silicon Valley leaders speak of a world radically remade by AI, I wonder whose world they’re talking about. Something doesn’t quite add up in this equation. Jack Clark has put it more vividly: “People don’t take guillotines seriously. But historically, when a tiny group gains a huge amount of power and makes life-altering decisions for a vast number of people, the minority gets actually, for real, killed.”

Disruption to the “creative classes” could produce an outsized political impact. I’m not exactly sure where people in the creative classes — say, writers or editors or artists6 or, to broaden the net, industries like consulting or advertising — rank in terms of the medium-term threat from AI-related job displacement. (Journalists per se have long lived with an anvil over their heads in a perpetually struggling industry.) These are the people I tend to hang out with. In our darker moods, we sometimes have conversations about who will or won’t have a job in five years. I suspect they’re at above-average risk, though — less threatened than, say, mediocre programmers but more than, say, someone with irreplaceable physical gifts like Victor Wembanyama. However cynical one is about the failings of the “expert” class, these are people who tend to shape public opinion and devote a lot of time and energy to politics. If a consensus develops among this cohort that their livelihoods are threatened, or that their children’s livelihoods are, I expect there will be enough political blowback that anti-elite pushback won’t be enough to overcome it.

I consult for Polymarket.

I have decent-sized holdings in Nvidia and other AI-adjacent equities.

Being able to outsource time-consuming tasks to computers might be good for small business that have less manpower. Although, I’ll note that when I submitted this particular story to ChatGPT for a copy edit like I usually do, it was grumpier about it than normal.

I’m not entirely joking about this. If AI produces a lot of wealth but increases free time for people with analytical mindsets, games like poker might become a vehicle to get out those competitive urges.

See also Matt Breunig and Ross Douthat for recent smart takes about this.

I think AI-generated art kind of sucks regardless of its technical acuity, and contrary opinions tend to reflect a misunderstanding of the purpose of art. But that’s a very hot take that would need its own essay.

Hi Nate,

Long time fan. I recently wrote a guide to AI catastrophe that I think is superior to existing offerings (it assumes less things, makes the case more rigorously, is intended for a lay audience, doesn't have weird quirks or science fiction, etc):

https://linch.substack.com/p/simplest-case-ai-catastrophe

Many of your subscribers likely have a vague understanding that some experts and professionals in the field believe that AI catastrophes (the type that kills you, not just cause job loss) is likely, but may not have a good understanding of why. I hope this guide makes things clearer.

I don't think the case I sketched out above is *overwhelmingly* likely, but I want to make it clear that many of the top people who worked on AI in the past like Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio think it's pretty plausible, not just a small tail risk we might want to spend a bit of resources on mitigating, like asteroids.

Nate, I'm pretty sure the AI companies are “Theranos”ing all of us at this point (okay, that’s a little extreme, I don’t think it’s outright fraud, but definitely overoptimism for the sake of pulling in investments). Like obviously LLMs are real and tangible, but the progress is becoming increasingly slow and the AI companies aren’t eager to own up to that fact. To take a rather infamous old example, strapping a calculator to a model because it doesn’t know how to do math doesn’t fundamentally fix the underlying issue causing the model to suck at math. Are these models still getting appreciably better or are they just taping a band-aid over a gaping wound over and over again?

I use AI for literature searching, primarily because search engines have become so terrible that only the AI models built into the search engines can turn anything up reliably. EVERY TIME, there is obviously incorrect information in the write up. Just patently incorrect. Sometimes it doesn’t even follow the assertions made earlier. The papers it turns up are fine, summarising a single paper is fine, but the moment you ask an LLM from a synthesis of multiple sources, the wheels inevitably come off. The “check this response” feature won’t even turn up most errors. It’ll find one line it can verify and mark that and ignore the other factual assertions. How does this tech cause massive, long-term technological disruption if the credibility of its output is worse than a coin flip?

Well, there is one way, dependency. It doesn’t matter if the models are good or not if students are trained to be dependent on them, but that’s not singularity.

I’m also still waiting to hear what their plan is to create new training sets. Most of the improvements so far have been from sucking in more training data. The problem is at this point a large amount of new content online is AI generated. We know that, for some reason (actually a fairly well understood one), training an AI on AI output causes model collapse. If you can’t separate AI output from human output, how can you create a pure training set that you haven’t already used?

This “no-ceiling” rhetoric may end up being correct, but the negative case is compelling to me and is not frequently considered (beyond the shallow chat bot critique you call out). Obviously big tech isn’t interested in that argument because they’re financially entangled with the AI firms, that means that all of the “experts” aren’t really able to be objective on the question. (As an aside, when you frame the question as whether OpenAI will *announce* AGI, I think 16% is fair odds based on how many times in history the definition of AI has changed and the number of times a company has announced something they didn’t actually create)