Don't discount American democracy's resilience

The U.S. has a highly popular democratic tradition, even as it battles an authoritarian element.

In the process of doing a lot of thinking lately about how it’s going in America1, I’ve found myself not really vibing with some of the pessimism I see elsewhere, the constant proclamations that the U.S. has crossed the Rubicon into authoritarianism.

It’s prudent to consider worst-case scenarios. What makes the situation especially hard to assess is that there’s no particularly clear precedent for the situation the United States finds itself in right now. No country with this long a democratic tradition has faced this much of a threat to it, and the U.S. is exceptional in general for being the wealthiest nation in world history, perhaps on the verge of a profound economic and technological transformation. No one should be confident about how the story ends. But it can also be hard to see the world through clear eyes when you’re constantly in crisis mode.

For instance, I think it’s reasonable to feel more optimistic about democracy after what’s happened in Minneapolis. Some of what’s been going down there is truly vile: check out this video of former Border Patrol chief Greg Bovino psyching up ICE agents in Minneapolis, for instance. “Arrest as many people who touch you as you want. Those are the general orders, all the way to the very top!” Bovino said. That’s about as authoritarian an attitude as I’ve seen in my lifetime in the United States.

But the people have pushed back. The normies are with the protestors, not the cops, and the White House has been in retreat, demoting Bovino last week.

To cut right to the chase, my critique is not so much that these pessimistic accounts overstate the threat to American democracy. Rather, it’s that they underrate the capacity of the world’s longest-standing democracy to play defense. Or if you prefer, they underrate the resistance. Both the capital-R “Resistance” in the form of things like the protests in Minneapolis, as well as Trump’s broader unpopularity.

Democracy vs. authoritarianism as a two-dimensional problem

It’s common to think of democracy vs. authoritarianism as existing along a one-dimensional spectrum. The Economist Intelligence Unit, for example, classifies countries on a scale from 0 (authoritarian) to 10 (most democratic). As of 2024, their last report, they rated the United States at 7.85, down from 8.22 in 2006. The score is likely to fall further when the 2025 edition is ready, reflecting the first year of Trump’s second term.

Since this is Silver Bulletin and we’re a unapologetically a little sports-obsessed, I’m tempted to liken these democracy ratings to the field position in a football game2, where the end zones are “dictatorship” and “pure democracy”. This metaphor provides for more agency than the abstract notion of a spectrum: field position reflects the net result of two sides pushing back at one another.

Still, field position can conceal the absolute strength of each side. In a Pee Wee League game between rival teams of 8-year-olds, the football might spend a lot of time in the middle part of the field. The same might be true in a game between the 2013 Denver Broncos (the most prolific offense of all-time) and the 1985 Chicago Bears (one of the best defenses), but that’s a very different matchup: the irresistible force meeting the immovable object. This is closer to the situation that the United States finds itself in. Trump is formidable in many respects. The Republican Party has completely rolled over for him. He’s incisive about targeting weakness, both in the opposition and in the design of the system. And he essentially gets to play with home-field advantage given current voting coalitions because rural votes are more valuable than urban votes in the Senate.3

However, Trump faces resistance from state and local governments in a highly federalized system, as well as from the courts4 and the Constitution, from media and cultural institutions. And most importantly from public opinion, which is often not on his side.

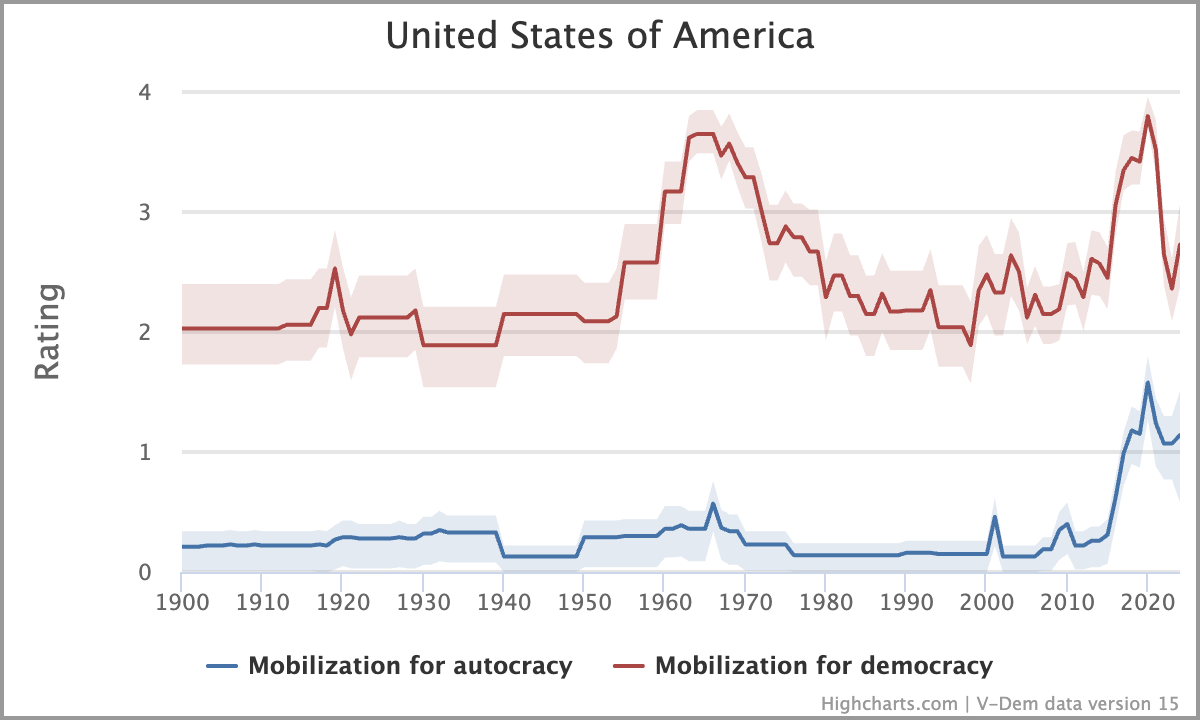

Another democracy scoring rubric from V-DEM (the Varieties of Democracy Institute) includes a pair of indicators that caught my eye: mobilization for democracy and mobilization for autocracy. From the V-DEM codebook, they are defined as follows:

Mobilization for democracy. Events are pro-democratic if they are organized with the explicit aim to advance and/or protect democratic institutions such as free and fair elections with multiple parties, and courts and parliaments; or if they are in support of civil liberties such as freedom of association and speech. This question concerns the mobilization of citizens for mass events such as demonstrations, strikes and sit-ins.

Mobilization for autocracy. Events are pro-autocratic if they are organized explicitly in support of non-democratic rulers and forms of government such as a one-party state, monarchy, theocracy or military dictatorships. Events are also pro-autocratic if they are organized in support of leaders that question basic principles of democracy, or are generally aiming to undermine democratic ideas and institutions such as the rule of law, free and fair elections, or media freedom. This question concerns the mobilization of citizens for mass events such as demonstrations, strikes, sit-ins. These events are typically organized by non-state actors, but the question also concerns state-orchestrated rallies (e.g. to show support of an autocratic government).

Again, these are just two out of many indicators that V-DEM considers. To calculate them, V-DEM relies on surveys of scholars, and there can certainly be biases introduced there. Still, it seems noteworthy that even in the Trump era, pro-democracy mass movements have been much larger in scope than pro-authoritarian ones. The No Kings protests and the Women’s March each turned out millions of people. The Black Lives Matter protests of summer 2020 (although a somewhat more complex example5) were by some measures the largest protests in U.S. history. The Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017 attracted mere hundreds, by contrast. A couple of thousand people stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

To be clear, “mobilization for autocracy” has increased in the United States. The insurrection at the Capitol could easily have produced the biggest rupture in the system since the Civil War. However, “mobilization for democracy” has increased along with it to levels not seen since the Civil Rights Era:

In fact, this sort of pattern is fairly common. Let’s look at the V-DEM scores for every country in each of the mobilization categories since Trump was first elected in 2016.6

Countries shown in red are members of NATO or the OECD. These are basically the United States’ peers: Western-ish, wealthy-ish, democratic-ish countries. Although the U.S. is in the middle of the pack globally in “mobilization for autocracy,” it ranks relatively high among NATO/OECD countries: 6th out of 44 countries. However, it also ranks 2nd out of its 44 peers (behind Poland, which has been through a lot) in “mobilization for democracy”.

Indeed, these measures are positively correlated.7 In wealthy Gulf States like the UAE or Qatar, you don’t need mass protests on behalf of the authoritarian regimes because the suppression of democracy is so complete8 that the regime’s power isn’t really in question. “Decreasing mobilization for autocracy in six countries may seem positive, but these are six countries that are autocracies, such as El Salvador and Iran. So it seems rather a sign of increasing autocratic dominance,” V-DEM wrote in one report that remarked upon this phenomenon. Meanwhile, in countries like Norway and Sweden, democracy is so firmly entrenched that there’s little need for demonstrations in support of it. For whatever cultural or historical reasons, some countries such as Greece rank high on “mobilization for democracy” and low on “mobilization for autocracy,” but these are more the exception than the rule. For the most part, pro-democracy mass movements emerge only when democracy is in question — whether through internal threats or, in the case of Taiwan, external ones like China.

Some of you will reasonably point out that Trump did prevail by one rather important indicator of mobilization: voting, having won the presidency twice in the past three elections. But that doesn’t mean there’s a majority of voters on behalf of autocracy. One reason I’m not fond of the comparisons between the contemporary U.S. and the authoritarian regimes of mid-20th century Europe is that there’s a much longer tradition of democracy in the United States. Whatever new vector in the conflict Trump represents is being layered on top of a deeply entrenched two-party system.

One should be careful not to conflate democracy vs. autocracy with Democrats vs. Republicans. To be clear, while Democrats are sometimes guilty of hypocrisy or of using the heavy hand of the state when it suits their purposes, I think Trump’s attempts to undermine the system have been much worse than anything Democrats have done.

However, most of the things that the parties argue about don’t have much to do with democracy per se. People voted for Trump for many reasons: inflation, immigration, lower taxes, and so forth. Sure, Clinton, Biden and Harris all campaigned heavily on the theme of “democracy.” But this might have struck voters as awfully abstract given the highly competitive nature of recent American elections. Or as excusing away bad governance or unpopular decisions that usually would be reasonable causes to vote a party out of office.

Voters are capable of making finer distinctions than many pundits seem to assume. (One ironically undemocratic tendency of some pro-democracy voices is in dismissing the importance of public opinion.) In a YouGov poll last week, a narrow majority (51 percent) of Americans supported the goals of Trump’s immigration policy. But only 27 percent of respondents supported how Trump has been implementing that policy. One can want fewer immigrants coming through the southern border while not wanting poorly-trained masked agents running around a Midwestern city killing protestors.

And when democracy has been under acute, tangible threat, Americans have resisted these moves. Only 18 percent of U.S. adults in the YouGov poll thought that “federal immigration agents were justified …. in the amount of force they used in shooting Alex Pretti in Minneapolis,” against 55 percent who did not. (Even among Republicans in the poll, only 41 percent thought the killing was justified.) Another time where there was there was this clear consensus was after the events of January 6. In a 2023 poll, only 12 percent of voters thought that “protesters”9 were defending democracy by entering the U.S. Capitol, while 58 percent thought they were threatening it.

To return to the football metaphor, one side is basically on offense when it controls the presidency and enough other institutions (e.g., Congress and the courts). You expect a team to make gains when it holds the ball. The question is how much the defense can limit the damage. Counting his first term, Trump has now been in office for 1,838 days. It’s a complicated question, but I don’t think you’d consider him to be one of the more accomplished two-term presidents. And the defense is likely to receive some reinforcements after the midterms.

Or better yet, you can create turnovers, turning a strength into a weakness. Democrats might be on the verge of that after Minneapolis: taking an issue, immigration, where the public was initially sympathetic to Trump and framing it as a question of authoritarianism and constitutional rights where a supermajority is on their side.

Initially, this was inspired by an update I’ve been working on to a series of predictions I issued at the start of Trump’s term. Yes, that’s still coming at some point soon.

A more fluid sport like soccer might be a better analogy, where offense can quickly transition into defense and back again, but American football ought to work well enough.

And to a lesser extent, in the Electoral College, although this advantage is diminishing.

There’s more resistance from courts than liberals sometimes give credit for, especially in the highest-stakes decisions.

Not every progressive cause is a pro-democracy cause.

That is, the scores reflect the average of years from 2016 through 2024 where a rating is available; V-DEM scores for 2025 aren’t ready yet.

The correlation is .31 overall and .49 among NATO/OECD countries.

And/or because citizens are happy enough with their material wealth so as to not agitate for democracy.

“Protestors” was the term used by the survey.

What about the unprecedented naked corruption and bribery? Trump is running the country like a third world corruption racket, the only comparable example that comes to mind is Eric Adams, who thankfully was just kicked out. They’re both scam artists. It still baffles me how Adams was allowed to run the city in such a brazenly corrupt way the more we learn about his mismanagement, lies, and bribes. Like with Adams, we are learning all the shit he did now that he’s out of office, it will take years to uncover the amount of money Trump stole from the public and all the other shit he engaged in.

I’m still not feeling optimistic. The corruption is so staggering and no one is being held accountable, it feels like we are entering into something different.