Is the Democratic Party dominated by progressives or by centrists?

No, and no. But compromise choices like Harris don’t always work out either. Here are the lessons we can draw from every Democratic nomination since 1968.

Perhaps the only thing the various factions of the Democratic Party agree upon is that Donald Trump winning two of the past three presidential elections has been a disaster for the party. But American political parties are resilient, so there’s a lot to fight over as they tangle for influence in the rubble.

Even during the shutdown, a point of relative unity for Democrats, the salvos continue. In the Atlantic this week, for instance, Jonathan Chait wrote that “after almost a decade of nearly unchallenged supremacy, the progressive movement’s hold on the [Democratic Party] is no longer certain.”

This “unchallenged supremacy” came as news to the progressive movement, which takes basically the 180-degree opposite view. “The party, we’re hearing already, needs to moderate,” wrote Ostia Nwanevu just after Kamala Harris’s loss, in a column whose headline declared that “long Obama era” was over. “Never mind the fact, and it is a fact, that the Harris campaign hewed to the political middle with extraordinary discipline,” he continued.

So, who’s right?

I often find value in Chait and Nwanevu’s commentary, which is why I’m going to pick on them: they’re both wrong.

Both of these perspectives are oversimplified and jaded. Trump has almost completely captured the Republican Party: there are differences between various MAGA factions, but they’re subtle. By contrast, Democrats are a typical “big tent” political party, full of disagreement, healthy or otherwise. It’s only natural after 2024 that the various sides are going to point at one another and say: “This loss is on you, bud; time for someone new in charge.”

But like the blind man and the elephant, that disagreement can be hard to get your hands around. Your perspective will differ if you’re focused on the actions of the capital-D Democratic Party versus the broader left-of-center universe and the people who seek to influence it through their words and writing. The Indigo Blob, I’d argue — basically my term for the mainstream media sans explicitly conservative outlets like Fox News — has careened from centrist to woke and now back to the center again. But the Democratic Party itself has a long tradition of seeking compromise between its factions — and it usually succeeds at achieving it. However, this hasn’t always produced highly compelling presidential candidates.

To make matters more complicated, I’d argue that there are really four Democratic factions fighting for influence, not two: it’s not a simple matter of progressives versus centrists. But I’m going to save that taxonomy of Democratic factions for a newsletter in the near future. Today, I’m instead going to run through every presidential nomination process since 1968, with an eye toward: 1) looking for regularities in how Democrats pick candidates and 2) pinpointing the sources of present-day progressive and centrist grievances.

A quick methodological note

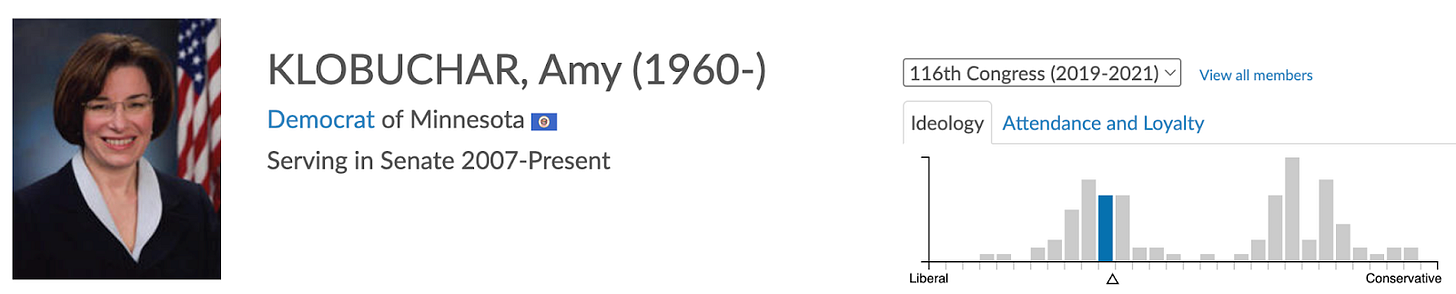

Throughout this story, I’ll sometimes cite DW-Nominate scores, which are a statistical measure of a legislator’s positioning on a left-right scale based on their voting in Congress. For instance, at the time she ran for president in 20201, Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota was more liberal than only 32 percent of other Senate Democrats in the Senate; that is to say, she’s relatively conservative for a Democrat. However, she was more liberal than 68 percent of the Senate overall, counting Republicans and independents. Thus, I’ll shorthand Klobuchar as a “32/68”, the number before the slash indicating her placement relative to other Democratic senators (higher scores = more liberal), followed by her score relative to the Senate as a whole.

I have some critiques of DW-Nominate, so I’ll notate some cases where I think it tells an incomplete story. It’s also only available for candidates who served in Congress at some point (so not, say, governors or mayors).2 But it at least provides for some sort of objective grounding to mix in with my stylized view of history.

1968

For much of the middle 20th century, we were in a de facto three-party system: Republicans, Northern Democrats and Southern Democrats. Southern Democrats sided with the rest of the party on the welfare state, but broke with them on civil rights and racial issues.3

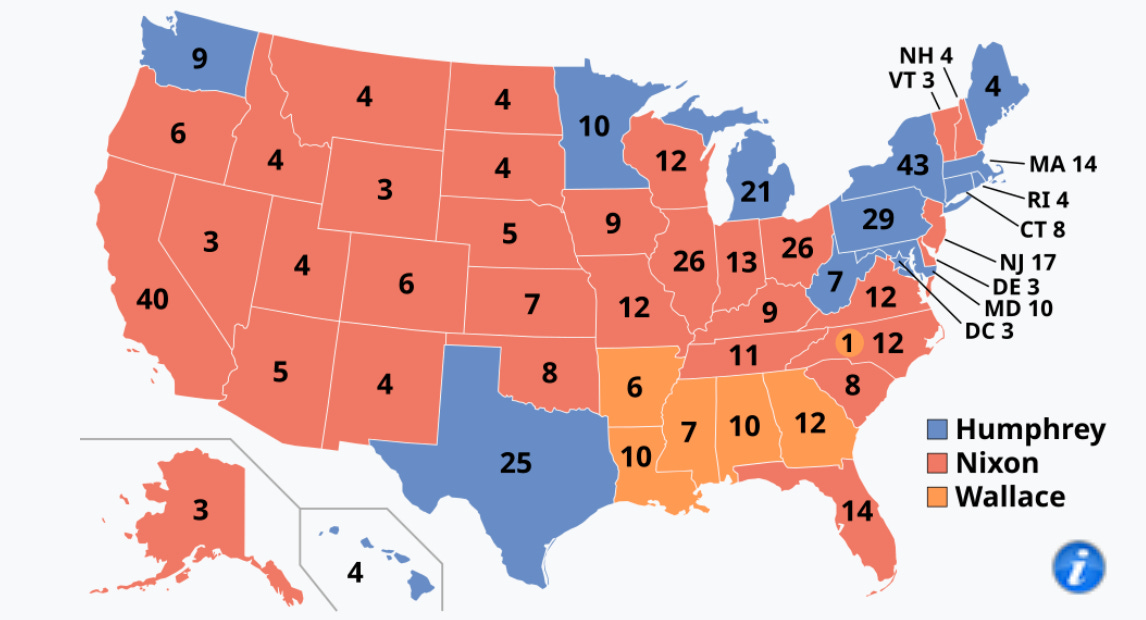

But this is roughly when that arrangement, which political scientists call the Fifth Party System, began to erode. In fact, by 1968, we were in the midst of a conservative vibe shift after the Great Society and the Civil Rights Era. Richard Nixon, adopting a Southern strategy that involved racial dogwhistles to culturally conservative Southern white Democrats, won a solid Electoral College majority against Hubert H. Humphrey despite just 43 percent of the popular vote, in part because the segregationist George Wallace won five Southern states:

Humphrey won the nomination at the infamous 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago, which was marked by protests against the Vietnam War both inside and outside the convention hall. The anti-war movement had also helped to tank LBJ’s hopes of running for a second elected term4 after he only narrowly defeated Gene McCarthy in the New Hampshire primary.

Humphrey, Johnson’s vice president, although a relatively liberal northern Democrat (his DW-Nominate “slash score” is 70/80), was nevertheless unwilling or unable to distance himself from LBJ’s support for Vietnam: the situation is perhaps analogous to how Kamala Harris couldn’t differentiate herself from the unpopular Biden last year. Considering the challenges he faced and LBJ’s unpopularity, Humphrey’s showing wasn’t that bad — he nearly won the popular vote. (Again, one might draw an analogy to Harris.) However, his selection — the last one before the McGovern-Fraser reforms moved the nomination process out of smoke-filled rooms and gave greater say to voters in primaries and caucuses — reflected what you might describe as characteristic Democratic risk-aversion. As of the time of the convention, Humphrey’s polling had deteriorated to the point where it was actually worse against Nixon than more liberal McCarthy (79/87). The best Democratic candidate might have been RFK (85/91), who launched his campaign with a speech calling for an end to the war, but he was assassinated three months later.

1972

The McGovern in “McGovern-Frasier” was George McGovern, a left-wing (96/98), anti-war senator from South Dakota. And it undoubtedly helped him to be playing a game that he’d written the rules for. In 1972, McGovern, Humphrey and Wallace each received about the same number of popular votes in the new process, which featured predictable regional splits. McGovern rarely led in national polls of Democrats. But he received far more delegates, taking advantage of caucuses and conventions. The result was the most unambiguously progressive Democratic nominee in modern history — and a landslide defeat to Nixon, who accused McGovern of supporting “acid, amnesty and abortion”.

1976

By 1976, the war was finally over, and a power vacuum developed in the Democratic Party after Ted Kennedy, the leading candidate in the polls, declined to run. The relatively unknown governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, emerged as the nominee in a result that a statistical model of the nomination process would probably have given long odds against.

Like McGovern, Carter understood that delegates kept the score, not states won or votes. His reputation for decency also played well in the aftermath of Watergate. There were not particularly ideologically sharp contours in the primary; the second and third-place candidates were fairly mainstream choices, Senators Scoop Jackson (40/73) and Mo Udall (60/78). Nor is Carter so easy to define. In contrast to the stereotype of Southern Democrats, he was fiscally conservative but fairly progressive on social issues. The 1970s were weird!

1980

There were clearer battle lines by 1980, with Kennedy (93/96) finally running and mounting a vigorous primary challenge to Carter’s left. But also, in an inversion of the usual dynamic of the more centrist candidate being more associated with the party establishment, Kennedy was a Kennedy, whereas Carter was still something of an outsider.

Carter prevailed before losing in a landslide to Ronald Reagan. In some circles, Kennedy was blamed for Carter’s November loss. But here’s one point where I’m sympathetic to Nwanevu: historically, you can detect some tendency for the left to be blamed when the situation is ambiguous instead. Because that isn’t quite fair to Kennedy: Carter had already been unpopular, with his approval rating mired in the 30s for much of the second half of his term. His weakness was more a cause of Kennedy’s challenge than the effect of it; for all we know, he might have given Democrats a better chance against Reagan than Carter did.

1984

Having netted only Carter’s one-term presidency in three elections under the new primary system, Democrats were starting to understand their rules better by 1984 — and, in fact, they also changed them to introduce superdelegates. That helped them to stage-manage the process and emerge with essentially a compromise choice in Walter Mondale after a contentious primary.

Mondale (83/90) was nobody’s idea of a conservative; instead, he was a throwback labor-left Democrat who had been Carter’s vice president. Still, he received overwhelmingly more support from superdelegates than Jesse Jackson and Gary Hart. The other insider choice that year was the former astronaut John Glenn (38/67), who would have made for a more centrist option but flamed out early.

Instead, the second-place finisher was Hart, who received nearly as many popular votes as Mondale and briefly surpassed him in national polls. And he’s a tricky guy to characterize: his DW-Nominate scores come out at 88/95, quite liberal, especially for a senator from the then-conservative Colorado. But his branding was that of a pro-business “Atari Democrat” — yes, that was really the term. Hart was a forerunner of what we might think of today as an “Abundance Democrat”, drawing most of his support from younger, college-educated voters. But Hart wasn’t a partisan warrior; instead, he suggested that the party needed to move on from the New Deal, which probably didn’t help him with superdelegates.

1988

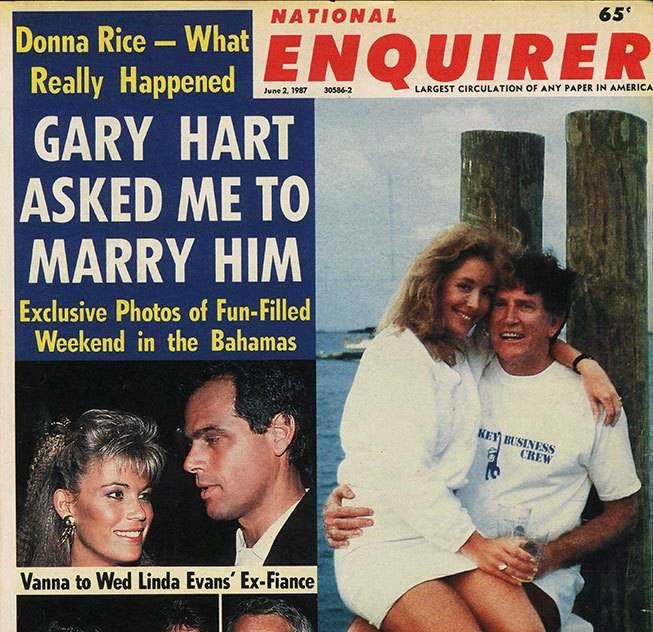

After Mondale produced the fourth Democratic loss in five elections, this time with even fewer electoral votes than McGovern, Hart might have been in the perfect position to win the 1988 nomination — if not for a National Enquirer cover depicting him having an extramarital affair aboard a yacht ironically named Monkey Business:

Democrats chose Michael Dukakis instead, who was eventually branded as a wimpy, soft-on-crime liberal by George H.W. Bush and Lee Atwater — think Willie Horton and the ill-fitting tank helmet. But that wasn’t what Democrats thought they were getting. Instead, Dukakis, who led Bush in early polling, emphasized his immigrant heritage and his state’s prodigious economic growth (the so-called Massachusetts Miracle) and also sometimes wore the “Atari Democrat” label. It wasn’t a particularly close nomination race thanks to Dukakis’s overwhelming support from superdelegates. But he and Jesse Jackson, in a solid second place, avoided a floor fight by agreeing to rewrite the rules to reduce superdelegates’ role in future contests.

1992

By 1991, with Bush’s popularity still high after Operation Desert Storm, the conventional wisdom was basically that Republicans had a permanent foothold on the presidency. It got to the point where Saturday Night Live titled its Democratic debate sketch “The Race To Avoid Being The Guy Who Loses To Bush”. Early polling frontrunner Mario Cuomo and others dramatically passed on the race.

So Democrats took their chances on a Southerner and one of the most unambiguously centrist nominees of modern times in Bill Clinton.

But by mid-1992, after high inflation and the afterglow of the Gulf War had worn off, Bush’s popularity had tanked to the point where he trailed in polls — first to Ross Perot and then, after Perot abruptly dropped out (he’d later re-enter) on the final day of the Democratic convention, to Clinton. If nothing else, this goes to show that a party nomination is always worth something. It’s hard to predict what political conditions will look like a year or two in advance at the time when candidates are making their go or no-go decisions.

1996

Despite Clinton’s political talent, Democrats endured a landslide defeat in the 1994 midterms, ending a 40-year streak in control of the U.S. House. The losses were sometimes blamed on “Hillarycare”, and indeed, Hillary literally accepted the blame (“So I take responsibility for that and I am very sorry about that”) for the losses suffered by her husband and fellow Democrats.

But by 1996, with Clinton’s popularity recovering and the economy soaring, there was no threat of a primary challenge. Instead, Democrats were beyond thrilled to nominate a candidate who had the chance to become the first Democrat elected to two consecutive terms since FDR. The mood was basically this:

Clinton took the opportunity to tack further to his right. As though to apologize for the characteristically Clintonian “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy (Clinton had pledged in 1992 to end the ban on gays in the military), he signed the Defense of Marriage Act into law in September 1996. The previous month, just a week before the convention, he’d passed welfare reform. These were usually significant acts of public policy for so late into a presidential year. And they served everyone’s purposes well enough: Clinton easily defeated Bob Dole, but Democrats only regained three House seats and actually had a net 2-seat loss in the Senate.

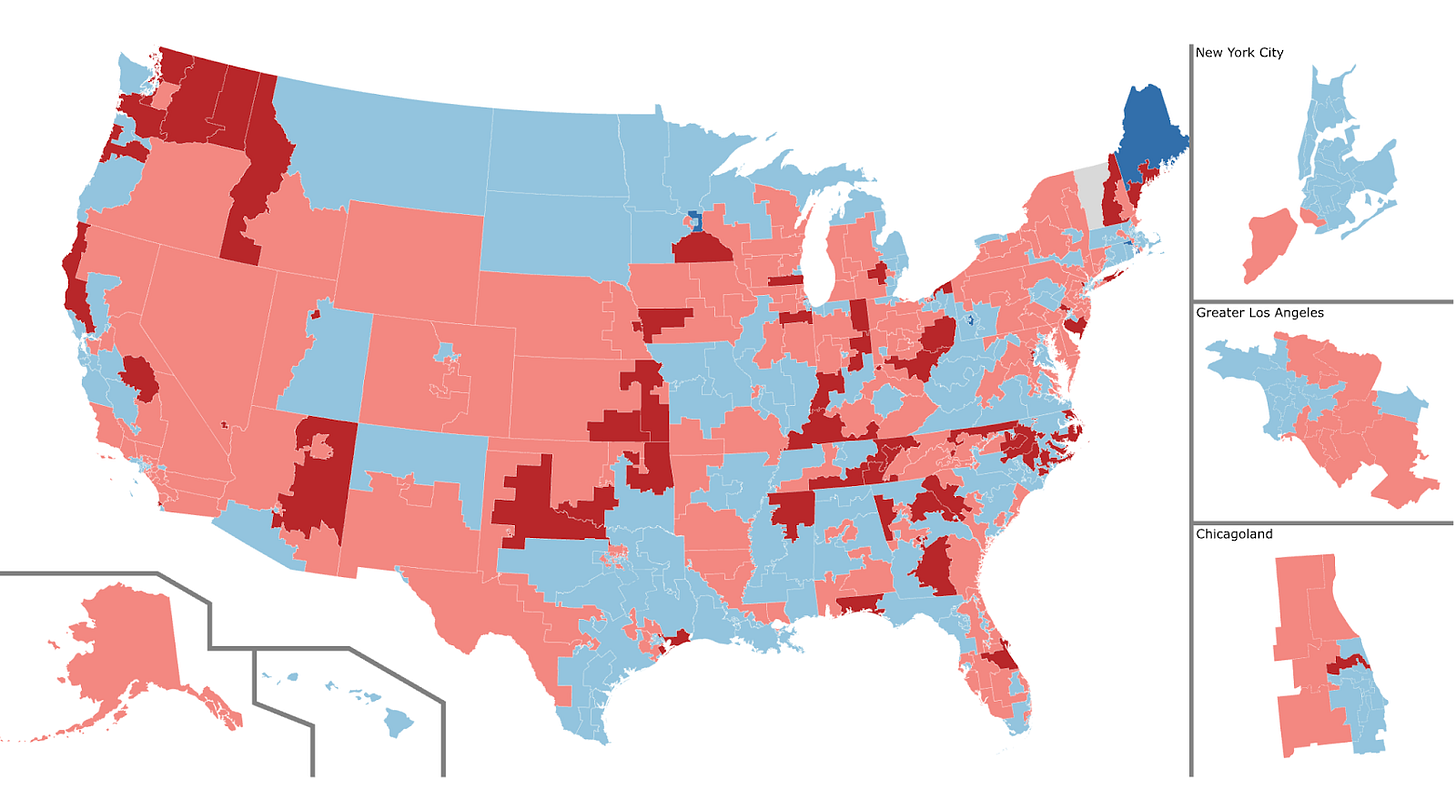

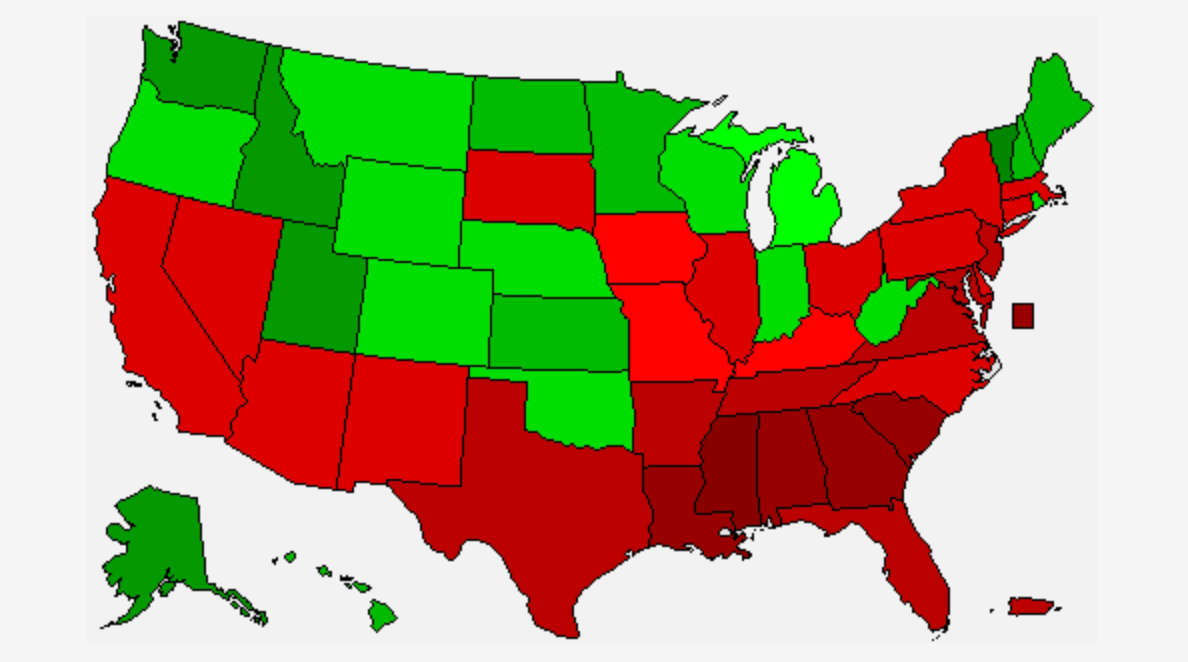

Still, there was a lot more going on in the midterms than just Hillarycare and DADT: a sharp rise in partisanship, and a significant step-change in realignment against the Democrats in the South. In what will become a theme, Democratic losses in 1994 were concentrated in rural districts in “flyover country”:

2000

Following an unusually strong 1998 midterm, with Democrats actually gaining seats in the House amid voter displeasure with Republican plans5 to impeach Clinton over the Monica Lewinsky scandal, Clinton’s VP Al Gore, won every state against Bill Bradley. The truth is, there wasn’t that much of an ideological contrast. Bradley’s DW-Nominate scores (53/78) were nearly identical to Gore’s (54/74), and he ran to Gore’s left on health care but to his right on education.

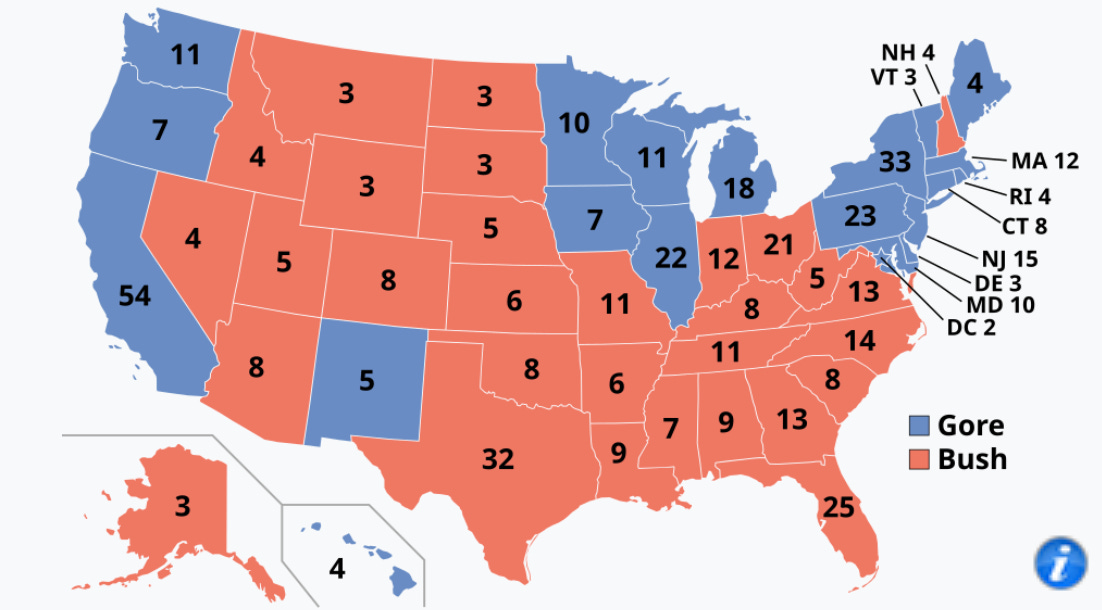

But the most lopsided contested nomination in the modern era — even Trump didn’t win every state last year — was followed by the closest general election ever, with Gore losing by a disputed 537 votes in Florida to George W. Bush. Despite being a fellow Southern Democrat, Gore’s map was much different from Clinton’s, bearing a close resemblance to the red-blue divide that remains in effect today (in the first election where the red-blue color scheme was standardized). Gore lost his home state of Tennessee, for instance, whereas Clinton had won it twice.

2004

Like Dukakis — maybe Democrats should simply avoid nominating candidates from Massachusetts? — John Kerry wound up being perceived as a (latte-sipping) liberal (and a flip-flopper to boot). But in 2004, Democrats saw Kerry differently: as a war hero and a more electable alternative to Howard Dean, one of the first candidates to harness the fundraising power of the Internet.

As with Joe Biden in 2020, Democrats consolidated around Kerry remarkably quickly, who won all but four nominating contests. Then they hedged their bets by pairing Kerry (85/70) with the more moderate John Edwards (70/39). It didn’t work. Kerry’s performance in the Electoral College wasn’t half-bad, but Democrats lost four U.S. Senate seats, including that of Minority Leader Tom Daschle.

2008

Bush claimed to have a mandate, but soon squandered it, beginning with his failed Social Security reform plan and Hurricane Katrina. And things only got worse for him from there, with the Iraq War growing more unpopular as the global financial crisis loomed.

To take stock for a moment, Democrats exited 2004 having lost seven out of the prior ten elections, with the three exceptions being the decidedly centrist Clinton and the quirky one-term Carter. One might have predicted that they’d go back to the well for another moderate southerner like Edwards. And indeed, there were some hints of moderation. The 2006 midterms were something of a last gasp for rural, Southern Democrats, who had actually picked up a handful of Congressional seats in a strong midterm. This was also a point of unusually high unity for Democrats, as Bush’s popularity cratered. Dean, the chair of the DNC, had developed a fifty-state strategy that called for running candidates everywhere who were good fits for their local electorates.

Edwards did run in 2008 and struck more populist themes than his Senate voting record might predict. But there were two heavyweights in the party. First, Hillary Clinton, who shared her husband’s instincts for triangulation but often picked the wrong battles, having voted to authorize the Iraq War despite compiling a fairly liberal 85/76 DW-Nominate score overall. And then there was Barack Obama (82/65), who was never quite as much of an underdog as the conventional wisdom suggested.6

Although the 2008 primary was famously contentious, it’s not one where the fault lines cleanly aligned to left-versus-center boundaries. Obama ran to Clinton’s left on Iraq, but also as a “post-partisan” Democrat (“We coach Little League in the Blue States and have gay friends in the Red States”) and his health care program was less liberal than Clinton’s. Instead, the splits were more demographic. Clinton won among Hispanic voters, non-college whites, and older Democrats. But Obama’s coalition of Black voters, younger college graduates, and independents who voted in the Democratic primary prevailed, in part because his team was much smarter about the delegate math.

Lingering enmity between the Clinton and Obama factions was put to rest by a slickly produced 2008 convention, mutual dislike for Sarah Palin, and the emerging global financial crisis, which gave Obama a tailwind against John McCain. This was when I’d begun to cover politics professionally — and for a year or two there, it was naively possible to imagine an enduring Democratic supermajority featuring pretty much every stripe of the center and left. That would turn out to be very wrong.

2012

Obama succeeded in passing health care reform, whereas Bill Clinton had failed. But it came at the cost of mammoth losses in the 2010 midterms. The first unmistakable sign of trouble was the Republican Scott Brown’s win in Massachusetts in a January 2020 special election after Kennedy died. Then came the midterms: the 63-seat loss for Democrats in the House was bad enough, but that actually understates the magnitude of the defeat. Because it occurred at the start of the decade, the election had cascading effects due to its impact on redistricting.

And Republicans wiped out most of the remaining Democrats from rural and Southern majority-white districts who had managed to retain their seats in 1994. Sometimes, shifts in party ideology have more to do with attrition than anything else. And the Blue Dog Coalition of moderate and conservative Democrats was literally more than cut in half after 2010.

Obama recovered to win re-election in 2012 following an essentially uncontested renomination and a well-run general election campaign. But there were some new undercurrents lurking just beneath the surface.

On the right, there was populism in the form of the Tea Party movement.7 Then, a few years later in the midst of Obama’s second term, we got something else on the left. Since my proposed term “Social Justice Leftism” has never really caught on, I’ll just go ahead and call it wokeness. There’s an inflection point in the use of terms such as “privilege”, “systemic racism”, ”triggering” and “marginalization” beginning at some point in roughly 2014 or 2015.

While I don’t want to turn this into yet another of the hundreds of essays you’ve probably read about wokeness, I don’t think you can understand the frictions within the Democratic coalition without accepting it as a salient element. Wokeness also looms large when people like me or Chait or Nwanevu write about politics because we’ve seen it up close. Journalism, along with academia, was on the front lines.

OK, fine, what is wokeness? The most obvious feature is the substitution of race, gender and other forms of identity for economic class as a focal point for analyzing political and social hierarchies. Other aspects include a confrontational approach to politics, the incorporation of various academic concepts such as “intersectionality” into mainstream political discourse, and attempts to gain hegemony over purportedly nonpartisan spaces through peer pressure or even the “deplatforming” of opponents.

And wokeness reflects the intersection of two trends. First, the increasing sorting of the party coalitions along educational lines8; it’s not a coincidence that it often borrows ideas and concepts from academia. And second, the influence of social media, which contributes to its confrontational ethos.

2016

So … was the 2016 Democratic primary contested on woke versus nonwoke lines, with Bernie and Hillary as proxies? Actually, the story isn’t quite what you might think.

Rather, Bernie Sanders’s surprisingly9 competitive challenge to Hillary Clinton that year reflected what I’d argue were more traditional party dynamics. An insurgent candidate from the left captured the hearts and minds of younger voters, while older ones backed the stodgier, safer, establishment-approved choice.

And although Sanders is a democratic socialist, he’s never really been a culture warrior. In fact, Sanders once took fairly conservative positions on immigration as well as gun control; he opposed the Brady Bill while a member of the House. These stances reflected both his representation of a rural state, Vermont, and that the correlation between views on “economic” and “social” issues is now much stronger than it once was.

In fact, it was Clinton who used concepts like intersectionality and terms like “systemic racism” in her campaign, while Sanders drew controversy for his opposition to reparations. And it was Sanders, shown in green on the map, who performed better in more rural, whiter areas.

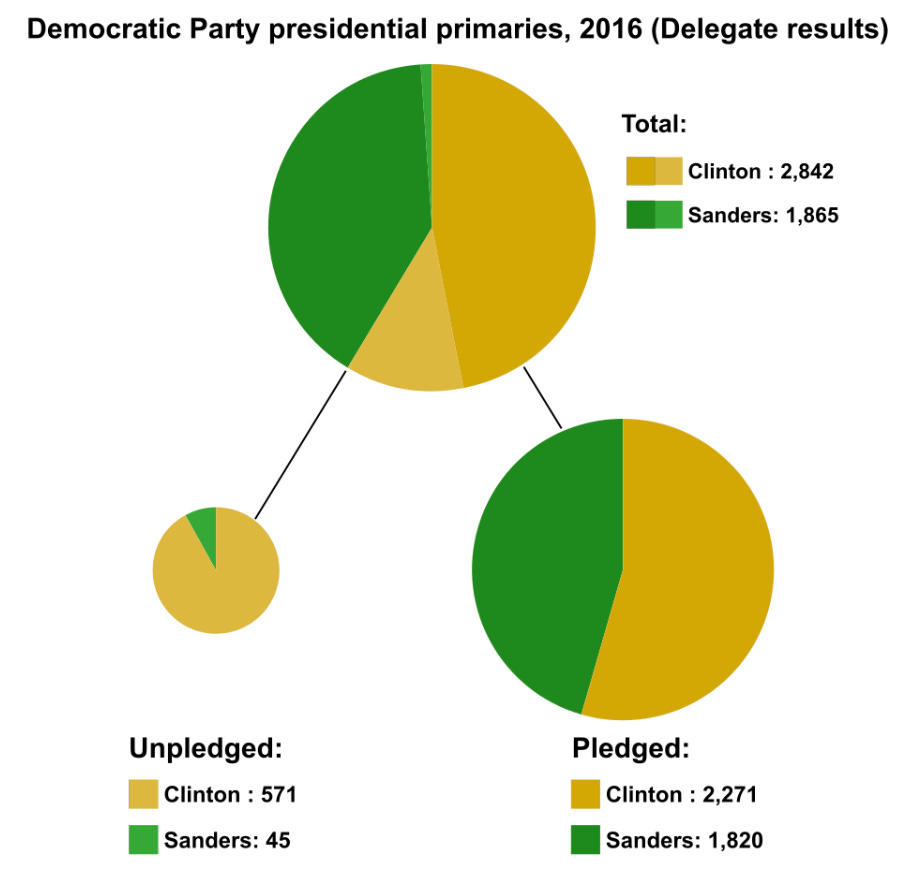

I also need to bring up another persistent Democratic point of friction: superdelegates. Technically, Clinton needed the votes of superdelegates10 to win in 2016, but that’s only because there were enough of them that her solid majority of elected delegates was not quite enough to achieve an absolute majority on their own.11

Still, while the notion that the DNC “rigged the primary” for Clinton is wrong — unlike Joe Biden in 2024, she actually debated her opponents12 — the fact that the establishment overwhelmingly lined up behind Clinton and then she blew it by losing to Trump anyway is an extremely understandable sore point for progressives.

2020

Ironically, this oversimplified reading of 2016 — that Sanders’s strong finish had proven that Democrats wanted their candidates to shift to the left — probably hurt Sanders and progressives in 2020. Sanders’s success in 2016 was more about economic populism than cultural leftism; Clinton was arguably the woker candidate. But by 2020, Sanders was backing decriminalization of border crossings and putting more emphasis on racial diversity. And his coalition shifted, losing much of its rural strength; Sanders easily won Oklahoma in 2016 but lost it badly in 2020, for example.

Most of the rest of the field was also racing to the left. Every Democrat on stage at the first debate, including Biden, raised their hand when asked if their health care plan “would provide coverage for undocumented immigrants”:

Harris was perhaps the most forceful in this positioning. As her campaign memoir reveals, she’s a consummately establishment-y figure, trying (often clumsily) to navigate the shifting tides in her party. And in 2019 and 2020, that meant, for example, checking yes on an ACLU questionnaire that asked if she supported “comprehensive treatment associated with gender transition” for “those in prison and immigration detention”, which later became the impetus for the infamous they/them ad. She also compiled an extremely liberal record in the Senate, with a 97/99 DW-Nominate score based on her voting in 2019 and 2020.

Biden (50/69) wasn’t the only relatively moderate candidate running; there was also Klobuchar, Pete Buttigieg, Michael Bennet (12/60), and eventually, American Samoa’s favorite, Michael Bloomberg. But the left lane was more crowded in a field that literally had more than two dozen candidates.

After Sanders’s tie with Buttigieg in Iowa and wins in New Hampshire and Nevada, Biden also benefited from a heavy hand from “party elites”, perhaps accelerated by a “flight to safety” as the COVID pandemic loomed, receiving the endorsement of Jim Clyburn ahead of the South Carolina primary and then a joint endorsement from Klobuchar and Buttigieg before Super Tuesday.

Sanders also eventually endorsed Biden — less grudgingly than he’d endorsed Clinton. And Biden beat Trump, while Clinton hadn’t. Exit polls in 2020 showed Biden capturing 94 percent of votes from Democrats that November, notably better than Clinton’s 89 percent in 2016.

2024

So … party unity for the win? Well, maybe. But Biden, perhaps in an attempt to keep the various Democratic factions happy, governed further to his left as a president than you’d have guessed based on his voting record in the Senate — and in ways that probably hurt him. He pushed ahead with a huge stimulus package that contributed to inflation. He signed executive orders on “environmental justice”, trans rights, and in a big priority for Sanders, student loan forgiveness. He relaxed security at the border, which later became a big problem for Harris.

There was also Biden’s choice of Harris as a running mate. She certainly had adequate qualifications for the job, with a considerably longer tenure in public office than JD Vance, for instance. But it’s rare to choose someone as your next-in-line after they flopped so badly in the primary. And although Harris has never been a favorite of the Sanders left, this choice was made with an explicit focus on racial equity. “Ms. Whitmer, a moderate, appealed to Mr. Biden’s political and ideological instincts, but selecting her also would have yielded an all-white ticket,” the New York Times reported at the time.

By the end of Biden’s term, the second biggest intraparty debate was probably over Gaza, but it didn’t spill over into significant friction at the party convention, as Harris says in her memoir that she’d feared. But by far the biggest fight was over Biden himself — whether to replace him, and who to replace him with. And this wasn’t really a progressive-versus-centrist fight at all. To be honest, I’d argue that it was really between those who were too blinkered by partisanship to understand the profundity of Biden’s problems and those who saw the issue with clearer eyes.

Still, the 2024 nomination was “contested” in the way political scientists usually apply that term. No, it wasn’t contested to any appreciable degree by the voters.13 The DNC put a heavy finger on the scale, refusing to sanction debates and rejiggering the schedule to put South Carolina (one of Biden’s best states) first.

Instead, it was contested in the old-fashioned way: by party elites, as was the case with 1968 and other nominations prior to the primary process. Even with Biden’s endorsement, it wasn’t trivial for Harris to wrap up the nomination essentially within 24 hours when party leaders as prominent as Obama and Nancy Pelosi were pushing for a “mini-primary” instead. As in 1968 with Humphrey, this can be thought of as a pragmatic compromise made under duress. Biden and his allies had leverage, and conditional on being forced to drop out, they wanted Harris to be the replacement.

It’s not clear whom Democrats would have selected if there had been a speed-run attempt at a primary — probably Harris. But as I’ve written about extensively, I don’t really buy Nwanevu’s notion that “the Harris campaign hewed to the political middle with extraordinary discipline.” For one thing, subsequent reporting, including Harris’s memoir, suggests a fly-by-night operation; there wasn’t all that much discipline about anything. For another, she tried on a lot of different brands — how quickly we forget about Brat Summer! — but really only in her convention speech was there an expressly centrist pitch. Instead, Harris disavowed a lot of previous positions without really disowning them. There’s a contrast here to someone like Zohran Mamdani, who made a show of apologizing for having called the NYPD “racist” in 2020. Harris was further constrained by her unwillingness to distance herself from Biden, either to the left on Gaza or to the right on any issue.

Tallying up the “score”

We’ve been through almost 5,000 words of this; I just wanted to err on the side of comprehensiveness in explaining why I don’t think either Chait or Nwanevu has this right. Progressives can cite grievances, including the expressly centrist Bill Clinton years, the party backing Hillary Clinton in 2016 when she lost, intervening fairly explicitly to help Biden against Sanders in 2020, and the fact that there have been relatively few truly progressive Democratic nominees in the modern era. Centrists can counter with the recent sharp shift leftward in cultural, academic and media institutions, and the leftward tilt of Biden’s governance, which was influenced by various progressive “groups” — though that cultural shift is now reversing itself. And both sides can lodge their complaints about Harris.

However, Harris is part of a tradition, alongside other examples like Dukakis and Kerry, of candidates whom Democrats perceived as relatively moderate not being read that way by the rest of the electorate. You can ascribe that to devious Republican ads — Willie Horton or they/them — but Harris’s stances in 2019 and 2020 gave Trump a lot of options to work with.

Perhaps that can be read as an argument for picking a truly left-wing candidate. The argument would go something like this: if Republicans are going to brand any Democratic nominee as a radical leftist anyway, you might as well pick somebody like Sanders who wears the label proudly and can speak with more authenticity than recent Democratic nominees have had.

But I’d argue for some different — if slightly complicated — conclusions.

First, voters appear to be more resistant to wokeness and other cultural indicators of progressivism than to Sanders/Zohran-style economic populism.

Second, the Democratic establishment is highly unpopular and for good reason. There’s no reason to trust its judgment when it still can’t even admit that Biden’s age was a problem, for instance.

And third, some compromises satisfy nobody. Harris was in her way a compromise between Biden or a mini-primary. Her selection as VP in 2020 was also a consolation prize to certain segments of the left, although not really the Bernie faction. However, Harris has never developed a distinct political identity of her own; instead, she has ridden the political tides of her party as they carried her, letting others define her. A bolder choice in 2028, whether it comes from the left or the center, might be better than what Democrats have been offering to voters lately.

DW-Nominate scores can vary somewhat over time; in this post, I’ll always cite the most recent score available as of the time the candidate ran for president.

Although for whatever reason, Democratic nomination processes have been dominated by candidates who have served in the Senate at some point, governors have been less common.

There was also considerably more heterodoxy within the Republican Party than there is now.

And third overall term; he succeeded JFK late enough to be eligible to run again.

House Republicans authorized an impeachment inquiry in October, but the actual impeachment didn’t begin until after the midterms.

Obama became a household name after stealing the show at the 2004 convention, and was always much closer to Clinton in Iowa than in national polls.

Although it was less heralded, there was also a dose of left-wing populism in the Occupy Wall Street protests of 2011

As recently as 2000, there had been basically no partisan split between college and non-college voters.

Surprising to me, anyway.

“Unpledged delegates” in official Democratic parlance.

The rules have since been changed — again — such that superdelegates are only activated if there’s no initial majority of pledged delegates.

Biden and his advisors were basically gaslighting people with their talking point about how millions of Democrats had voted in the primary. No offense to them, but the alternatives were Marianne Williamson and Dean Phillips, and Phillips, who entered late, was largely shut out of media coverage from Biden-friendly outlets.

EVERY Democrat in Congress, both House and Senate, and including nominal "independents" Bernie and Angus King, is a co-sponsor of the 2025 Equality Act, which would make gender self-ID instantaneous and unquestionable at all places of "public accommodation" (essentially, any business that serves the public). Any man would be able to enter any women-only space, place, event, etc, at his own personal whim.

That tells me that the "progressives" completely control the Democratic Party.

Marjorie Taylor Green, Elon Musk, RFK Jr., Tulsi Gabbard. What do they all have in common again?

The idea that the MAGA coalition isn't diverse is crazy. They are, however, extraordinarily united--largely due to a common foe.