Why Biden failed

He made a triple devil’s bargain: with the pandemic, his age, and a Democratic Party that can’t get its priorities straight.

Donald Trump, the 45th President, will also become the 47th President at noon on Monday, and we have you covered with a trio of long politics newsletters that we think you’ll really like. This is a final reflection on the outgoing 46th president, Joe Biden. Then, we’ll have two forward-looking pieces to run during the week. One (paywalled) is a set of probabilistic predictions on what will happen during Trump’s second term. The other (free) is a story placing the moment in a historical context. Are we at the beginning of a new conservative era, or will the pendulum soon swing back to the left? It’s a great time to subscribe if you haven’t signed up yet.

I have hardly any recollection of January 20, 2021, the day that Joe Biden took the Oath of Office. That may be because his speech wasn’t very memorable. In staccato bursts and simple sentences, delivered to a sparse, socially-distanced crowd, it didn’t contain much soaring rhetoric or policy substance. But it did offer a lot of promises, promises that Biden was never going to be able to keep.

The speech echoed a framing Biden had used in his acceptance speech that summer at the Democratic convention: that of a polycrisis. At the DNC, Biden had spoken of “four historic crises, all at the same time, a perfect storm”:

The worst pandemic in over 100 years. The worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

The most compelling call for racial justice since the 60’s. And the undeniable realities and accelerating threats of climate change.

In his Inaugural Address, Biden again pledged to “resolve the cascading crises of our era.” In fact, he upped the ante. The speech wasn’t humble: Biden compared himself to Abraham Lincoln after signing the Emancipation Proclamation, promising a solution to “systemic racism.” “The dream of justice for all will be deferred no longer,” he said. And with the inauguration conducted in the shadow of January 6, there was a new addition, a fifth critical threat: an “attack on democracy and on truth” and a “rise in political extremism, white supremacy, domestic terrorism that we must confront and we will defeat.”

A presidential election defined by the pandemic

Politically, this framing had been effective. In the AP exit poll in 2020, 39 percent of voters said the country was heading in the right direction, and of those 91 percent voted for Donald Trump. However, 61 percent said the country was headed down the wrong track, and 80 percent of them voted for Biden. Pessimism prevailed — comfortably in the popular vote, though narrowly in the key Electoral College states.

Intellectually, however, this “everything-bagel” list of topics had always been dubious, combining an acute, once-in-a-century crisis — the COVID pandemic and its attendant devastation of the economy — with two chronic problems, racism and climate change, that liberals tend to regard as existential threats while other voters do not.

The connections are hard to see unless you take a highly intersectional approach to politics. In a cynical way, the pandemic had actually been a respite from bad news on the climate because the decline in economic activity had temporarily reduced global CO2 output. How the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis policeman had spun, in the middle of this pandemic, into a broader “racial reckoning” is something that you could write an entire book about, meanwhile. Following Floyd’s death, the number of Americans citing racism as the most important problem spiked to 19 percent even among all the other challenges the country had to contend with, its highest level since the late 1960s:

But by the time of Biden’s election in November, the racial awakening was reverting to the mean. In the AP exit poll, only 7 percent of voters cited racism as “the most important issue facing the country,” and almost all of them were Democrats:

Instead, the pandemic and the economy still loomed overwhelmingly larger. But given how they were inextricably tied together, a partisan split had emerged. Voters who listed the pandemic as the top issue overwhelmingly chose Biden — and the ones who picked the economy, Trump.

In the early days of the pandemic, the political imperative was basically to get the case and death numbers perpetually streaming on cable news as low as possible — Trump had infamously complained that more testing had only made the case counts higher. There was a fair amount of consensus in public policy — every state had recommended school closures in March 2020.

But the run-up to the election had become a time of increasing debate about the unprecedented trade-offs Americans faced, increasingly reflecting a red-blue divide.1 The Floyd protests, endorsed by public health officials who had condemned other public activity, marked one early inflection point. It was associated with an emerging partisan split, not just in pandemic attitudes but behaviors, a divide that only grew so as to produce profound differences in vaccine uptake later.

What Biden needed for the return to normalcy he promised was for the case counts to get low and stay low — that was the only way out of the trade-off. Unfortunately, as Biden warned during his inauguration, the country was about to enter “what may well be the toughest and deadliest period of the virus.” COVID deaths peaked in January 2021 — the worst week of all had been the week of January 6, in fact — and were far more widespread throughout the country than in the spring wave.

The deeply strange vibes of four years ago

If Biden’s inauguration had been forgettable, the day I remember most clearly from this period given my line of work was November 7, 2020. That’s the Saturday when the major networks called the election for Biden, four days after Election Day. My friends had ambitiously made a lunch reservation in Brooklyn; I figured I was a longshot to make it because I’d been doing more or less wall-to-wall TV coverage for ABC News.

It had been clear to me for a couple of days — really, since Wednesday morning — that Biden was highly likely to win as returns gradually trickled in from Pennsylvania, Georgia and other states. But the networks had been extremely conservative about declaring an Electoral College winner. My role, as George Stephanopoulos periodically “threw” to me in an improvised TV studio2, was to brush up right up to the line of saying the race was over without saying that exactly, which would have violated all sorts of network decorum protocols. I’d wander through Central Park between TV hits, feeling giddy because I was sitting on a secret. I knew what was on the next page — Donald Trump’s tenure in the White House would soon be over.

I imagined the pandemonium in New York City once the secret was out: car horns blaring and people taking to the streets in joy and relief. Then, that Saturday, my vision was fulfilled. At 11:24 a.m., CNN called the race for Biden, and ABC News and other networks soon followed. I fled the office as soon as I could: my bosses and I both understood that the network had plenty of other talking heads to put the moment into historical context.

It was a blissfully, unseasonably warm day in New York. I walked across Central Park to take the scene in, caught an Uber to Brooklyn to make my brunch, and found what was basically a spontaneous day-long street festival. We wound up at some rooftop party that was decidedly not in compliance with COVID protocols, and I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who hadn’t felt so free in almost a year.

Then, the next Monday at 6:45 a.m., basically the first possible moment that it could after the election was decided — the timing wasn’t entirely coincidental3 — Pfizer announced auspicious vaccine results, saying its products blocked not only severe outcomes but also transmission at high rates. Plus, the end of the election is always a relief if you’re covering it. It would take some patience, but after a dark year, there was a yawning bright light at the end of the tunnel.

Even in victory, Biden got mixed signals from the electorate

But Biden hadn’t delivered the complete repudiation of Trump that polls — showing a massive 8.4-point popular vote lead — had been projecting. That’s why the election took four long days to call. Biden’s popular vote (4.5 points) and Electoral College (306-222) margins had been perfectly solid, and the migration of Georgia and Arizona into the blue column had enhanced its visual appeal on the map. But in the end, the tipping-point state — Wisconsin — voted for Biden by only 0.6 percentage points. Trump made gains in many areas, including South Texas, South Florida, and major cities, that would foreshadow his return to the White House four years later. If Trump’s handling of the pandemic hadn’t been so clumsy — he did get some of the big things right, including Operation Warp Speed and a stimulus package that quickly got the economy back on its feet — he might have been reelected.

The ambiguous message from voters seemed a lot more favorable for Democrats after January 5. That was the day Democrats won two Senate runoffs in Georgia, giving them control of a 50-50 Senate based on VP-elect Kamala Harris’s tiebreaking vote. Republican turnout had lagged, in part because Trump had preoccupied himself with questioning the integrity of the presidential vote count in Georgia and even trying to get the results overturned, which would later result in still-pending criminal charges. It was a delicious irony: the bunging efforts that began with the Four Seasons Total Landscaping news conference had culminated in Democrats improbably winning control of the Senate, giving Biden far more wherewithal to implement his agenda.

For obvious reasons, the buzz didn’t last long into the next day. But the events of January 6 have also never been easy to place into context. Whether you want to call it a failed coup, an autogolpe, an insurrection, or a protest grown dangerously out of hand, I’m on the side that says it was really bad. But it could also have been much worse, with members of Congress injured or killed.

Biden, despite a lot of effort — including making it the centerpiece of his aborted 2024 campaign — was never able to persuade Americans that January 6 had been on the same magnitude as a threat to the republic as September 11, for instance. Why not? Well, it’s hard to persuade people based on near-misses: thwarted attacks or narrowly averted disasters. Even actual disasters don’t always spur action when the inertia is high enough: America remains woefully unprepared for the next pandemic.

But I also think you can place some of the blame on the Democrats’ polycrisis framing (often echoed by a liberal establishment that over-selects for negative emotionality, less politely known as “neuroticism.”) If everything is an existential crisis, then nothing is. You’ll begin to suspect people of crying wolf. Or you’ll say, YOLO, if we’re all fucked anyway, let’s blow it all up, have some fun, and vote for Trump.

All of which is to say Biden arrived at his inauguration at a strange moment in American history. There were the vaccine announcements, but the pandemic raged on worse than ever. Democrats’ triumph on January 5 had become their terror on January 6. The largest popular vote defeat for an incumbent since 1992 was, nevertheless, an election Biden came less than 50,000 votes away from losing.

Biden was an accidental president

In high-risk, high-stakes times like these, where you’re well outside the parameters of the usual playbook, it can be tempting to be a hero. And if you listen to his inaugural address, that’s clearly how Biden saw himself. Or perhaps even as a savior: the speech contains quite a bit of religious rhetoric. “The Bible says weeping may endure for a night but joy cometh in the morning,” Biden said. He asked Americans to place their faith in him: “Take a measure of me and my heart.”

But trying to be a savior — ending the pandemic, saving democracy, and, on top of that, delivering justice from systematic racism! — is precisely what you don’t want to do during extraordinary circumstances or under exceptional stress. I explore this theme at length in my book, which includes interviews with dozens of risk-takers, both quant types and people like former astronauts and fighter pilots. “Don’t be a hero” is advice I heard consistently. Instead, stick to basic blocking-and-tackling. Identify the most critical problem and laser-focus on it until it’s solved. Probably not two problems at a time, but sometimes that can’t be avoided. Certainly not five simultaneous crises, though. Especially if you have no plan other than “unity,” which Biden described as the “elusive” ingredient to “overcome these challenges.”

This was perhaps especially true for Biden, an ordinary man in extraordinary times. If you simulated the world 1000 times with slightly different initial conditions, I’m convinced that both Barack Obama and Trump would become president fairly often — whatever you think of them, they have self some self-evident star talent. Biden is the political equivalent of what in poker we’d call a “grinder.” He’s been at the same casino every day for decades, playing in the same low-to-mid-stakes game. Like any grinder, he’s occasionally crotchety, sometimes complaining about the increase in parking prices or the broken soda machine. But he’s affable enough — he knows everyone and is a good reader of people on and off the tables. And at these stakes, he’s a solid, winning player. But when he’s tried to take shots at bigger games, it hasn’t gone well. Moreover, he’s now well into his seventies and well past peak form.

Then you turn on the TV one day, and this grinder from your $2/$5 game improbably has a huge stack of chips in the World Series of Poker. The truth is, he’s been lucky to get there, blessed by the deck and winning nearly every all-in for a week straight. But he comes to precisely the opposite conclusion: that after a lifetime of bad breaks and being underestimated, he’s finally getting the results he deserved all along. He’s badly overplaying hands, making heroic calls and raises, especially toward the end of the day once the fatigue sets in. Before you have time to text your buddies from the cardroom to turn on and watch the show, he’s busted out.

Biden had a distinguished career as a public servant but was lucky to become president. He was lucky to be chosen by Barack Obama as vice president in 2008 after finishing with 0.9 percent of the vote in the Iowa caucuses. And he was lucky to be one of the few candidates running in the moderate lane among the more than two dozen Democrats who sought the 2020 nomination, who took somewhat the wrong lessons from Bernie Sanders’s success in 2016. Now, you have to give Biden credit for the relationships he built in the party, which encouraged party leaders like James Clyburn to rally behind him even after disappointing finishes in the first three states. But he may have been lucky that it worked so well — that fears about the electability of Sanders, combined with the “flight to safety” on Super Tuesday just as the pandemic was coming to American shores, would catapult him virtually overnight to a commanding position in the polls.

And Biden was lucky, too, that Trump bungled the pandemic so severely. That’s why he was elected, not because voters wanted FDR 2.0. In the exit poll, just 40 percent of voters said they mostly or always agreed with Biden’s “positions on important issues facing the country” — the same tepid fraction as for Trump.

Out with the old polycrisis, in with the new one

Biden was popular at the time of his inauguration, but his approval ratings flipped negative as of Labor Day 2021 and never turned back around. Some of this was the inevitability of the honeymoon period that most presidents get wearing off, but there was a particularly sharp downturn in August and September.

What was happening at this time? Well, a lot of things. You might even call it a polycrisis.

First, there were the supply chain backlogs and rising inflation. This was right when it became hard to claim that the early spring uptick in prices had been “transient.” In fact, things were rapidly getting worse:

Second, there was the withdrawal from Afghanistan, including Kabul falling to the Taliban in mid-August.

Third, there was immigration, which was surging to record levels on the southern border after changes to asylum policy and an increase in demand for labor:

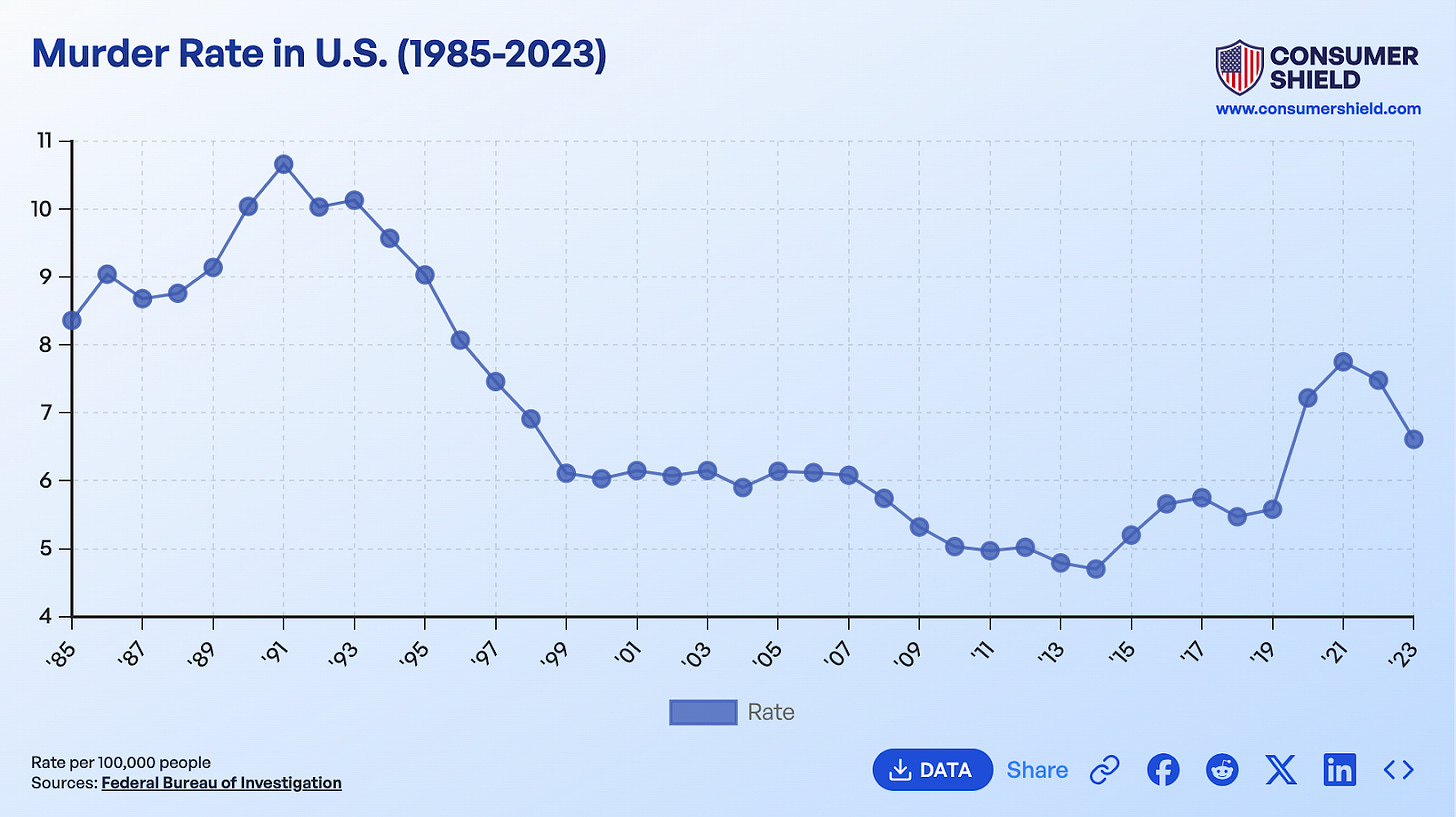

Fourth, there was a spike in crime, with the homicide rate surging to its highest levels since 1996:

Fifth, there was increasing fatigue with the racial reckoning, with perceptions of Black Lives Matter turning negative at about the same time that Biden’s approval ratings did:

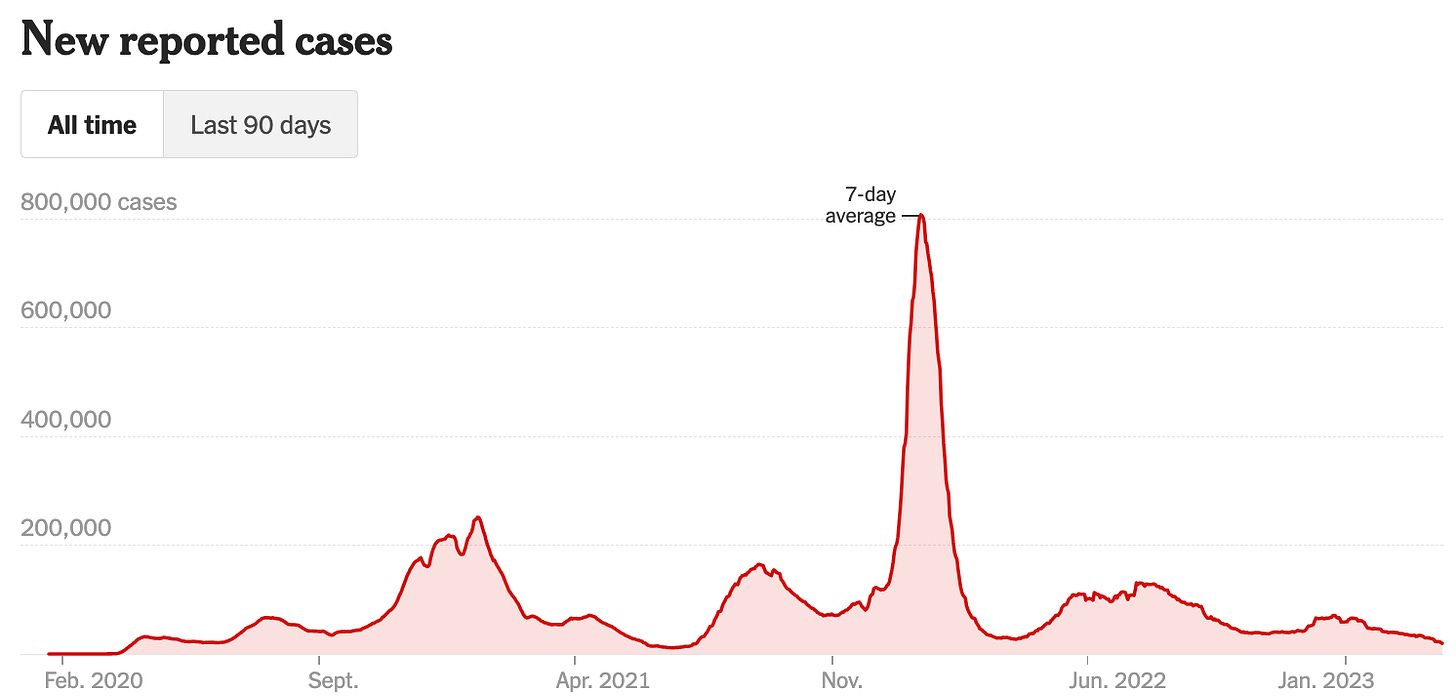

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there was still COVID — plenty of it:

Though the case fatality rate was lower than in 2020 because of immune protection from vaccines and previous infections, the number of new cases rose sharply from June through September 2021 due to the Delta variant — and then reached nearly three times their previous peak in January 2022 amid Omicron. Moreover, there were the cultural battles over COVID, which were more contentious than ever since Americans had long ago lost their patience. Battles over airplane mask mandates, vaccine passports, constantly changing CDC guidance, vaccines that weren’t as effective at stopping transmission as those studies had initially promised, and especially over school closures. Although there were increasingly few exceptions, American schools didn’t fully re-open for in-person learning until January 2022, according to UNESCO data.

By July 2022, perceptions that the country was going in the wrong direction were among their highest-ever levels, worse than at any point even in the annus horribilis of 2020:

Several of these factors improved from about that point onward. There were no more nasty COVID waves, and inflation slowly began to decline, as did homicide rates. (Immigration levels took longer to fall, however.) But while perceptions of the direction of the country improved, Biden’s approval ratings did not — save for a half-year reprieve in late 2022 that, happily for Democrats, coincided with a relatively strong midterm for the party. Instead, they entered a slow and steady decline beginning in early 2023, interrupted only by a brief sympathy bounce after Biden was finally forced from the presidential race in July 2024.

The reason for this — I think pretty obviously — was mostly Biden’s advancing age. Even in the 2021 inauguration speech, you hear a few slurred words. But based on plenty of subsequent reporting, Biden’s condition was steadily and self-evidently getting worse from roughly the midterms onward. Americans weren’t buying the White House’s attempts to gaslight them about it and cover up his shortcomings.

I’ve written a lot about Biden’s age. But it wasn’t just an issue for his reelection bid — it also affected his ability to govern effectively.

Dylan Matthews at Vox has a great, well-researched critique of Biden’s inability to prioritize under the American Rescue Plan and the Inflation Reduction Act. The government spent more than it probably should have, especially at a time of rising interest rates. And some of the programs Democrats did choose were bogged down by other polycrisis priorities: climate provisions and “racial equity” red tape. The spending was tremendously effective in stimulating the jobs market but at the cost of higher inflation, historically a bad trade-off from a presidential popularity standpoint. And Biden didn’t have a lot of shiny objects to point to for all that spending. Many infrastructure programs are only now coming online, in fact, with Trump set to receive credit for them.

Without being a fly on the wall, it’s hard to know precisely which decisions were affected by Biden’s declining mental bandwidth. Even at peak performance, Biden was always a wheeler-dealer type who tried to calibrate the demands on him from the various wings of his party. And even though he might not have recognized his good fortune, Biden was done a lot of favors by his party — the 2008 VP nomination, the 2020 presidential nomination, and overlooking a history of racially insensitive remarks — and owed them a lot of favors back.

Still, most people know from wrangling older parents and relatives that there are some constraints to manage once they reach Biden’s age. One is that it becomes challenging for them to handle when more than one thing goes wrong at once, so you have to limit the number of items on their plate or the number of potential points of uncertainty. But Biden’s instincts were precisely the opposite, promising to save the country from the polycrisis.

The other is that they’ll have their share of bad days — and persuasion becomes more difficult on a bad day. Both for your sake and for theirs. It requires a lot of mental and emotional bandwidth to get someone to come around to your point of view. On a bad day, the default modes instead are either to become cranky — demanding rather than persuading — or to become a pushover, declining to stand up for yourself because other people are dug in and they have more energy.

Biden showed both of these modes — the crankiness evident in his reluctance to leave the presidential race (he remains in bitter denial about his chances of winning). But he also was sometimes reluctant to fight for his instincts even when they would have served him well. Biden was initially worried that the Build Back Better package was too big, Matthews reports, but couldn’t parry the onslaught of competing demands from various constituencies within the party. He also went against his initial instinct in choosing Harris as his running mate. According to contemporaneous New York Times reporting, Biden would have preferred the “political and ideological instincts” of Gretchen Whitmer — but faced opposition from progressive groups who didn’t want an all-white ticket during racial reckoning summer.

And both those reported incidents happened in 2020 when Biden was sharper than he is now. It’s not clear how in command he is in any sense as his term ends, from allegedly being unaware of his own executive orders to, just last week, endorsing a bizarre interpretation of the Equal Rights Amendment, pushed for by activist groups, which implied that it was effect as the 28th Amendment when it very much is not.

So how much of this is Biden’s fault?

In the end, Biden made what was essentially a triple devil’s bargain in exchange for winning the 2020 nomination and the presidency. First, he sold people on a quick return to normalcy from the pandemic when it would instead take until summer 2022 thanks to reinfections, new variants, and sharp divisions over mitigation measures. The extent to which this is his fault isn’t so clear. I have plenty of critiques of the White House’s handling of COVID — and plenty of critiques of Trump’s — but COVID is a uniquely wicked problem. Biden gambled on COVID going away when vaccines became widely available, and it didn’t work out. But he made matters worse by promising not just to solve COVID but also to save democracy and even deliver racial justice.

Second, he misread his mandate between his savior complex and the constant whispers in his ear from Democratic interest groups. Anointed by the party for his electability, he instead governed as a fairly left-wing president, from major issues like immigration and the size of the stimulus package to others like student loan forgiveness and his administration’s interpretation of Title IX. And he picked a vice president with a mediocre electoral track record despite his misgivings based on pushback from progressive groups, but then never really entrusted her with much responsibility, or to replace him in office or on the ticket.

Third, he reneged on what many voters took as an implicit promise to be a one-term president. (Though he never said this outright, and recent reporting suggests he wasn’t decided either way until midway through his term.) Even in 2020, about half of voters questioned whether Biden had the mental capabilities to serve effectively as president. Given how people typically age as the enter their early eighties, everyone around him should have seen this coming, in other words — and planned accordingly, especially once Biden’s deteriorating condition became a poorly-kept secret. It is probably not too cynical to suggest that by the end, Biden became a proxy president for whomever had his ear, whether his advisors, “the groups,” or family members trying to manage his campaign despite severe conflicts of interest — and they didn’t want to lose their access to power.

Trump will make his own version of these mistakes, beginning with his second inauguration speech tomorrow. At 78, he’s just as old as Biden was at the start of his term. He’s bragged of a “massive” mandate when his narrow popular vote win very much wasn’t — Republicans barely held onto control of the U.S. House and might have lost the presidency if Biden had stepped aside earlier to make way for a candidate who had more distance from him than Harris. Trump is also subject to all sorts of unelected, outside influence, including from Elon Musk — only instead of Biden’s susceptibility to peer pressure, he’s unashamed of his pay-to-play tendencies. And Trump will articulate his own dark version of a polycrisis, from immigration to crime to foreign threats to the “woke mind virus.” Here’s hoping that whomever takes the Oath of Office four years from now will learn the lesson after what will be three party switches in a row.

Even with the benefit of almost five years of hindsight, public opinion on pandemic handling isn’t easy to get a handle on. That’s partly because revealed preferences might not match stated ones — people were often less cautious than they were supposed to be — and because the pandemic possibly impacted polling itself. (COVID-hawkish voters were more likely to stay home and thus had more time to answer surveys.)

Actually, the repurposed FiveThirtyEight podcast set.

A group of left-leaning public health officials had sent a letter to Pfizer urging it to change its protocols so a vaccine announcement wouldn’t be made until after the election, and Pfizer complied.

The sense I get from the Biden administration is a bubble.

1. The pandemic. There was plenty of evidence, very early on, that mutating strains were reinfecting large numbers of people. I remember reading the news and being boggled that everybody was talking like the vaccines meant that the pandemic was done. Either the Biden admin wasn't paying attention or they just buried their heads in the sand.

2. Inflation. Economists like Larry Summers and Mohamed el-Erian warned the Biden team not to pass the third stimulus package because of the risks of reigniting inflation. Then when inflation rose the official line from the administration was that inflation was "transitory". Both the Fed and the WH were so slow to react that by the time they did anything inflation was baked into the economy, a condition that still persists to the present day.

3. Illegal immigration. Anybody with half a brain could have predicted that there would be issues with allowing millions of people into the country unvetted. Surely there would be some criminal element? What about the impact on local resources and communities?

4. Ukraine. The Biden admin was convinced Ukraine would be toast within a few weeks. The country's survival caught the administration by surprise. Consequently there was no plan for supplying military aid to the Ukrainians: what level would be unacceptable to the Russians? Thus the slow leak of wartime materiel--no long range missiles or artillery because it could allow Ukraine to strike targets inside of Russia, followed by a decision to provide long range missiles. Then no tanks would be provided, followed by a reversal and a decision to send M1's. Then no fighter jets, followed by a reversal and a decision to provide F-16's. Then ATACMS...

Even worse is there exit strategy at all in Ukraine? When would the US be able to declare victory? I doubt that anyone in the WH or State Department has any idea and so there has been zero effort to communicate anything to the public. Is it surprising that the public decided that aid to Ukraine represented a "forever war" with possible existential consequences and turned to Trump for a solution?

Over and over again we see the Biden admin unable to ever get out in front of an issue. They were blindsided over and over again even when what was coming down the pipe was obvious to anybody with an iota of common sense. The Biden campaign sold the country on a message that it represented a return to competence. When it became apparent that the opposite was the case that marked the start of Trump's return to power.

I did not make it to the end of the article.

For every good point there 5 more that are absurd.

I thought I was signing up for considered opinion, not partisan politics dressed up like considered opinion.

Unsubscribing.