When you pick a VP, you're picking a future presidential nominee

Elections have consequences, so "future political considerations" are probably more important than their role as "governing partner".

This will be a relatively straightforward post. I’m pressed for time this week battling a book deadline, as well as preparing a two-part subscribers-only NBA preview — now’s a great time to consider becoming a paid subscriber if you’re a hoops fan!

I’d encourage you to read Astead W. Herndon’s profile of Kamala Harris in the New York Times. Herndon’s story is very deeply reported and doesn’t shy away from tough questions about Harris’s political future and why she was chosen as Joe Biden’s running mate. This passage stuck out to me (emphasis mine) and inspired this post:

Biden’s advisers say he selected who he felt would be the best governing partner, independent of race, gender or future political considerations. Because of Biden’s age, however, and his promise to be “a bridge’’ to ‘‘an entire generation of leaders,” Harris’s selection was immediately interpreted as a sign that a nominee who might serve only one term was already setting up his successor. “By choosing her as his political partner, Mr. Biden, if he wins, may well be anointing her as the de facto leader of the party in four or eight years,” read the Times article that announced her selection in August. But that was not the campaign’s thinking, Biden advisers told me, arguing that he chose Harris as a running mate for 2020 and a governing partner for his first term — not necessarily as a future president.

“It was a governing decision,” Dunn said to me during an interview. “Who can be president, if necessary? But really, Who can be a good partner for me in terms of governing and bringing this country back from the precipice?”

The vice presidency was often a relatively obscure role during the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. As the Senate’s website reports, “of the 21 individuals who held that office from 1805 to 1899, only Martin Van Buren was subsequently elected president”.1

Two things happened around the middle of the 20th century: the VP began to take a more public role in the television era as a de facto cabinet officer, and the parties gradually shifted to a system of primaries and caucuses where the public played a progressively larger role as compared to party bosses.

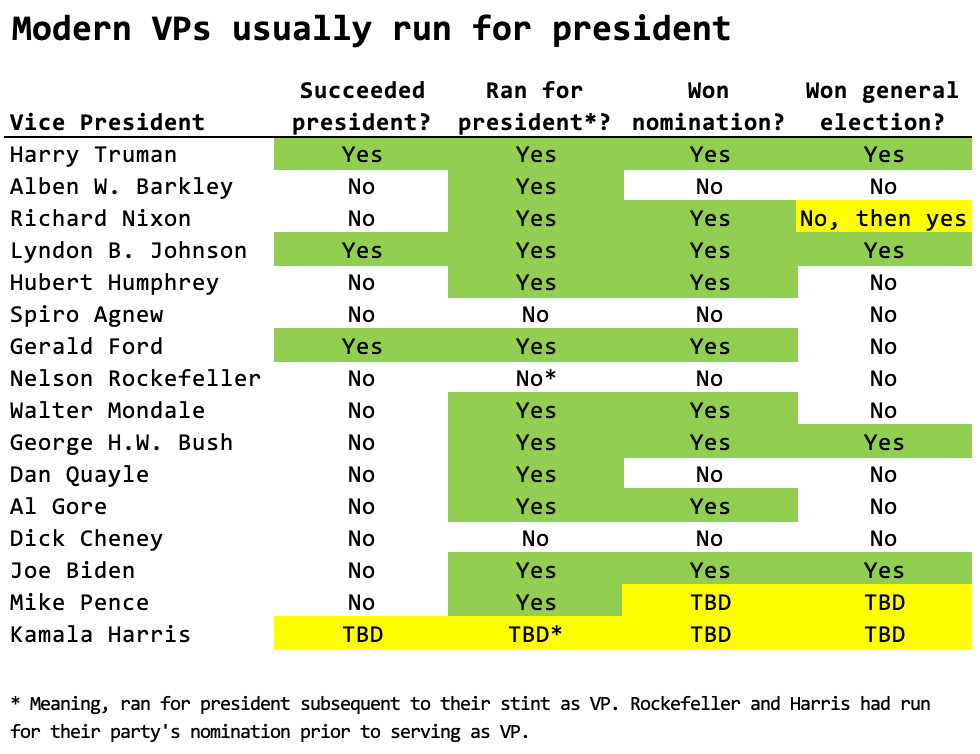

The result is that vice presidents2 are often the first names that voters have in mind when they think about who their party’s presidential candidate will be in the next election. In fact, if the VP isn’t seen as the natural successor, it may lead to a lot of questions, as Democrats are now asking about Harris. A large majority of VPs run for their party nominations themselves — and more often than not, they succeed in obtaining it:

Of the 15 post-WWII vice presidents who had the opportunity to run for president subsequent to serving as veep3 12 of them did. Excluding Mike Pence, who is still an active candidate for the 2024 Republican nomination — although it’s very hard to see him winning — 9 of the remaining 11 were successful in that bid. And then 5 of the 9 won the general election. (Although Nixon won in 1968 — not on his first try in 1960.) The only VPs during this period who didn’t for president themselves were Spiro Agnew, who resigned amid a scandal, Nelson Rockefeller, who was something of a caretaker for Gerald Ford after Watergate and who was replaced on the 1976 Republican ticket by Bob Dole, and Dick Cheney, who always maintained that he was not interested in running for president himself.

Of course, it’s not clear if we should take the Biden advisers’ claims in the Times article literally. Drawing attention to Harris’s qualifications as a “governing partner” is a better framing for the White House than saying she was chosen for her race and gender, although the story makes clear that was a pretty big factor. It also draws attention away from the question of how well Harris would hold up as a presidential candidate — which between her notably unsuccesful run in the Democratic primaries in 2020 and her poor polling against Trump is in doubt.

There’s also an implicit tension in Herndon’s story: amid understandable voter concerns over an 80-year-old president, the White House can’t seem to decide whether to elevate Harris or diminish her profile. Biden’s allies — even Nancy Pelosi — have sometimes seemed to praise Harris only through gritted teeth. The policy assignments she’s gotten — the Democrats’ possibly-doomed-from-the-start push for voting rights reform4 and presiding over immigration policy toward Central America — are thankless ones that weren’t going to set her up to succeed. It’s a deeply weird situation that Herndon’s piece captures well. The bottom line is that future presidential nominees probably do need to give ample consideration to the popularity and the political acumen of their running mates.

Four others succeeded to the presidency after the president died, but none later won election himself.

Though not losing vice presidential candidates, who have a poor electoral track record.

Meaning, not yet counting Harris.

Although the article says voting rights was an assignment Harris wanted.

Here’s a crazy idea: Maybe people should be selected for important jobs based on merit, not their race and gender. Lest we forget Kamala won 2% of the 2020 democrat primary vote and called Biden racist at one of the debates.

This whole piece feels like it ignores Obama-Biden '08.

Obama chose a governing partner -- or at the very least, an old white guy who could reassure voters wary of a young Black guy -- not a successor.

Yet despite the assertion in the piece that "if the VP isn’t seen as the natural successor, it may lead to a lot of questions," there were no questions about Obama's strategy at the time -- indeed, it was widely seen as the right one.

Bush-Cheney '00 feels similar -- a wisened veteran paired with a younger guy that some people had concerns about. No one expected Cheney to run after Bush's terms.

So two of the three President-VP combos of the 21st century (prior to Biden-Harris) don't follow the supposed rule that you need to pick a future presidential nominee. (While of course Biden did become a nominee, that's more incidental than anything. He became the nominee four years after he was out of office. Far as I can tell, every other person identified as having run for president post-VP did so at the first available opportunity -- either immediately following a term-limited president, or in the next election after a loss for a one-term president.)

So why is Nate so convinced that presidents must choose a VP who would be a viable successor? It seems like there are multiple logical paths to making that choice.