Trump's jobs data denialism won't fool anyone

Firing the BLS commissioner won’t prevent the effects of tariffs. But it will reduce American economic leadership and increase uncertainty for businesses, workers and investors.

I’ve had a fun weekend1 visiting family in Kansas City, but I figured this story was timely enough to be worth publishing on a Sunday. Also, time flies: It’s August, which means that it’s time for a new Subscriber Questions post, ideally this week unless further news intervenes. You can submit your questions in the comments to SBSQ #22.

If you’d asked me 20 years ago, when I made a living playing online poker and running projections for Baseball Prospectus, I would have told you that, of course, I’m a Data Guy. Treat the numbers with caution, because it’s easy to build bad models or otherwise screw up in umpteen ways when working with complex statistical data under deadline pressure. But at the end of the day, we all have to make decisions based on incomplete information. Businesses particularly face this problem: new hires or capital investments typically have a long time horizon. If you’re not going to make these choices based on your best estimate of the situation, given the relevant uncertainties — well, what exactly are you going to base them on?

These days, I’d say my relationship with the Data Guy label has become more fraught. In one of my particular subfields, election forecasting, there’s been a lot of bad work, which probably did more to misinform the conversation than contribute to it. And more broadly, I do buy to some extent that “science has been politicized”. Sometimes I've seen the admonition “just trust the numbers” used as a blunt insturment to suppress legitimate dissent. Data is collected by and interpreted by humans, and human error and bias play a role at every step of the process.

The important thing is to be right, and probably 90 percent of the time, going through the rigor of kicking the tires on the data2 and then explicitly modeling a situation helps you get there. But I’ll give a little more weight these days to the mesoscale rather than the micro. Having a good bullshit detector — heuristics honed by life experience — comes in handy that remaining 10 percent of the time.

When it comes to economic data produced by the United States government, however, people play that 10 percent “get out of jail free” card far too often. And usually, they’re the ones producing the bullshit, often to spin away politically inconvenient data.

U.S. economic data is pretty reliable

I’ve worked a lot with data produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and other federal agencies. In fact, an economic index based on a half-dozen of these statistics is part of our presidential election forecast, so we’ve pulled this data all the way back to World War II.3

And I consider it to be of very high quality. When BLS data is revised as more information becomes available, it’s meticulously documented and explained. For more on how this works, including just how difficult the BLS’s job is and how it’s being made harder by declining survey response rates and cuts to federal agencies that track economic activity, I’d strongly recommend this edition of the Odd Lots podcast with Bill Beach, the former BLS commissioner under Trump 1.0 and Biden. It might not be the most riveting interview, but one thing that comes through is just how much of a straight-shooter he is:

And yes, U.S. government economic data is revised — more for some data series than for others — because measuring something as complex as the modern American economy is an incredibly challenging task. Moreover, the BLS and other federal agencies are essentially trying to serve two purposes at once. On the one hand, they’re hoping to provide actionable information as fast as they reasonably can to employers, investors, job-seekers, policymakers and the Federal Reserve. On the other hand, they’re trying to formulate a “permanent record”, data that is treated as ground truth in future economic analysis. Those imply taking different positions in the unavoidable trade-off between speed and precision.

That doesn’t mean the BLS doesn’t face challenges like the ones that Beach outlined. A particular problem in recent reports seems to have been in overestimating state and local educational jobs, for instance.

And there’s also a more subtle factor at play. When data is published as part of the official record, there’s going to be a tendency to do things “by the book” in a way that establishes greater transparency or more consistency with past methods. Tyler Cowen considers this a “bias” of its own kind, and perhaps there’s something to that. Sometimes, when we’re publishing a model at Silver Bulletin, there will be times when I don’t think it’s handling a particular situation well, reflecting either a weird one-off circumstance or a potential change from the past regime of data that the model is trained on. But I’m usually reluctant to make ad hoc changes midstream in what we publish publicly. On the other hand, if I’m actually betting on something, I don’t necessarily care so much about the propriety of keeping up consistency — I just want to be on the right side of the wager. So if there’s something that catches my eye4, I’ll gamble (literally) on deviating from the process. We probably don’t want government agencies having that sort of attitude, though.

The job numbers suggest the economy is slowing, and Trump is in denial about it

On Friday, the BLS released its monthly Employment Situation Summary, more informally known as the “jobs report”. The jobs report is actually two separate surveys: a survey of households, from which the unemployment rate is derived, and a survey of “establishments” (businesses), which is where the “headline” number comes from showing how many jobs were gained or lost in the previous month.

This latter figure, officially called “total nonfarm payrolls,” is considered more reliable and is the one that tends to move markets and public perception. (It’s also the one we use in Silver Bulletin models.) That’s partly because it includes a considerably larger sample size. The BLS surveys approximately 120,000 businesses and government agencies each month for the establishment survey, some of which have dozens or hundreds of employees. By contrast, 60,000 eligible households are surveyed, which might have one or two members of the workforce each.

The headline payrolls figure wasn’t good on Friday: 73,000 net jobs added in July, lower than the recent average of around 200,000 jobs added per month from July 2023 through June 2025. What was worse, though, were the revisions to the past two months. May’s figure was revised downward by 125,000, and the government now estimates that just 19,000 jobs were added that month. And it was basically the same story for June’s figures, which will be revised again next month. Instead of 147,000 jobs, as initially estimated last month, the figure has been revised to just 14,000 jobs.

The three-month average of 35,000 jobs added is still positive at least — but just barely so. The last time it was negative was during the pandemic, when more than 20 million jobs (!) were lost in a single month in April 2020 — and before then, in late 2010, as the economy was still sputtering its way out of the Great Recession, contributing to a terrible midterm for Barack Obama.

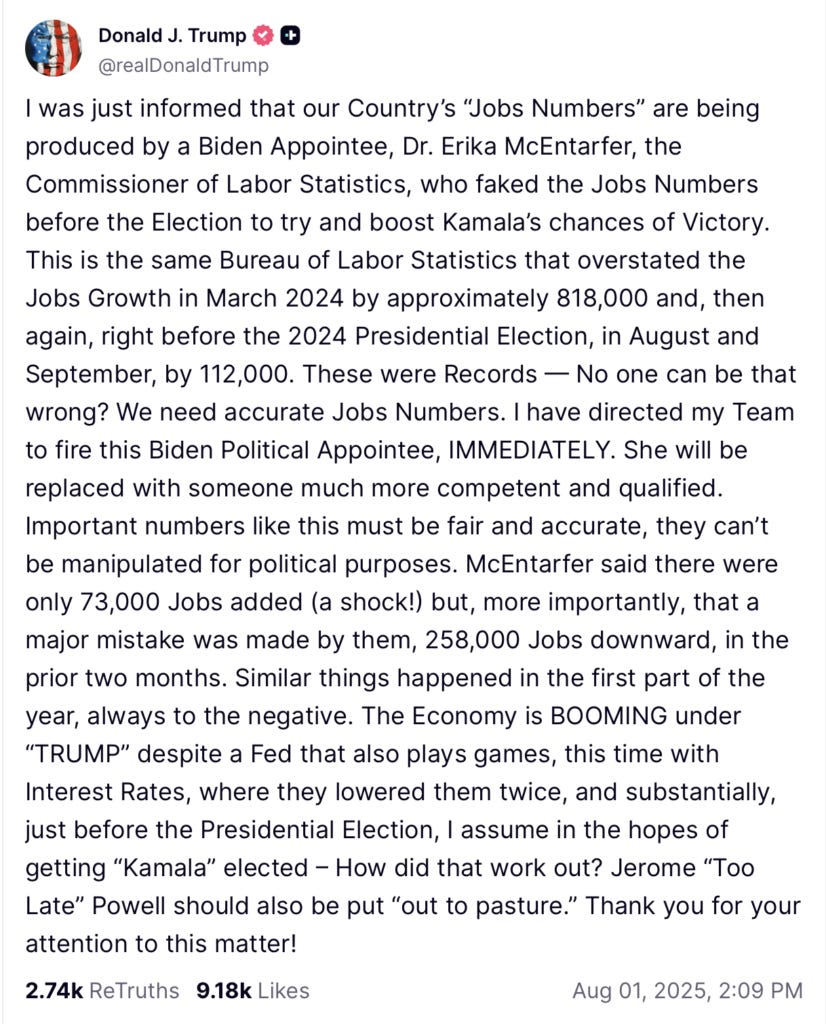

The White House initially put on a cheery face, putting out a tweet that celebrated the 73,000 jobs, which I compared to the New York Jets congratulating themselves for having won five games last season (they lost the other 12). By Friday afternoon, however, Trump had demanded the firing of Erika McEntarfer, the current BLS commissioner who was confirmed 86-6 by the Senate under Biden in 2024. I suppose I’ll let you see the president’s rationale for this in his own words as he posted them to Truth Social:

These were big revisions, but well within historical norms

Each monthly payrolls figure is actually revised three times: once in each of the first two months after initial publication (so July’s 73,000 figure will be re-reported in August and then again in September) and then again each January as part of the BLS’s annual benchmark revisions. For the rest of today’s newsletter, I’m just going to ignore the benchmarking process and focus on the first two monthly revisions. Here’s what those monthly revisions have looked like for the past two years of jobs data:

There are two obvious things to note here. First, the revisions are often quite large, swamping the initial signal. For instance, August 2024 was initially reported as a better month (+142K jobs) than July 2024 (+114K), but after revisions, August was actually slow (+78K) whereas July was fine (+144K).

Economics reporters at major news outlets are often too quick to treat the initial figures as gospel, declaring whether the report was a “beat” or a “bust” relative to expectations, and fail to inform their readers about the routinely large revisions and the difficulties in estimation. All of this feels a little too familiar: it’s the same thing that happens when news organizations breathlessly report polling data without considering the margin of error and other challenges for surveys.

Second, the trend in recent revisions has been negative, including — as Trump alluded to in his Truth Social post — for all months so far of Trump 2.0.

This is actually common enough, too, though. Empirically, the revisions in the BLS jobs report aren’t purely random; instead, there’s some positive correlation in the direction of revisions from month to month5, sometimes producing long streaks of upward or downward revisions. This implies that they don’t purely result from sampling error; instead there can be some pervasive statistical biases from month to month, especially when the economy is facing some sort of trauma or disruption. This may reflect the sort of lower-case “c” conservative “bias” that Cowen describes: a reluctance to change methods even when the underlying situation is changing.

I’ll show you more data on this in a moment — but first, it’s important to note that statistical bias isn’t the same thing as political bias. Revisions were also mostly downward for Biden during the 2024 election campaign, except for the last figure reported just before the election on Nov. 1, when the initial number was nearly negative before being revised upward to +43K.

Moreover, if the BLS had been out to get Trump, revising numbers downward wouldn’t be the way to do it. The revisions usually don’t get as much media attention as the headline figures. If May’s number had initially been reported as just +19K jobs instead of being revised down later, and June at +14K, there would have been more concern from investors for the past couple of months and more of a narrative that Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs, announced on April 2, were already taking their toll on Main Street.6

But as compared to the long run, the May and June revisions are relatively pedestrian. The largest change ever to an initial jobs figure ever after two months came in March 2020 as the pandemic hit American shores; initially reported as a job loss of 700,000, it was later revised to nearly 1.4 million instead.

Under the circumstances, though, this was understandable given the magnitude of the losses. The next month, April, the BLS initially reported that 20,537,000 jobs (!) were lost. This was later revised to −20,787,000, which counts as a large revision (−250K) relative to the usual monthly changes — but not as compared to the unprecedented disruptions the pandemic caused.

And currently, there are about 160,000,000 jobs in the U.S. according to the payrolls report. The absolute value of revisions7 has averaged about 60,000 jobs over the past decade, which is only about 0.04 percent of total payroll employment.

So you have to sort down to the fifth page in the table of the biggest revisions before the June 2025 revision of −133K jobs pops into the window. Since 1979, the effective margin of error on the initially-reported headline number, enough to cover 95 percent of the changes in the first two monthly revisions, has been around 160,000 jobs. So neither May nor June even counts as an outlier in a statistical sense.

You can also sort the table by month, in which case you’ll find evidence for my claim that there are often more problems at economic turning points. Pandemic job loss was initially underestimated in March and April 2020. But then the recovery was also underestimated, with initial reports lowballing job growth for 11 consecutive months from April 2021 though February 2022 — no help, by the way, to Biden, who was trying to sell a story of a robust labor market despite high inflation. Meanwhile, revisions were negative for nine consecutive months from June 2008 through February 2009 as the global financial system was coming unraveled.

The downward revisions reflect what businesses and economists were worried about

This is very much not financial advice. For the record, I own a fair amount of equities, and I’m not planning on making any changes to my portfolio. But it’s possible to read all of this as being rather bearish. Economists were wondering why the tariffs weren’t having more effect given gloomy consumer and employer sentiment numbers.

Even though Trump has backed out of some tariffs, they still represent the largest effective tariff rate since under Smoot-Hawley in the 1930s. If government agencies have trouble dealing with unprecedented situations8, it could be that this portends future downward revisions, as was the case in the acute stages of the pandemic and the global financial crisis.

I’m cribbing some of this from Joe Weisenthal, the Bloomberg reporter who is the co-host of Odd Lots. Weisenthal noticed that basically all recent jobs gains are from the health care sector, which is presumably going to grow in perpetuity as the American population ages. Meanwhile, outside of health care, the one big boon to the economy has been the extraordinary capital investments in AI. But while this AI spending may be great for the stock market9 and can even produce some NBA-style compensation packages for superstar engineers, it probably won’t result in a lot of (human) employment broadly and of course may wind up displacing jobs in the end.

So we’ve got the AI boom and zombie-like growth in health care as the population ages. And perhaps not much else — although as Josh Barro notes, there are some complications around immigration.10

In April, the chances of a recession in 2025 were trading above 60 percent at Polymarket as investors — in line with the overwhelming majority of academic economists — predicted a severe effect from the tariffs. Now, recession chances are trading at 15 percent. That’s slightly higher than 12 percent before Friday’s report, but we’re probably not going to get a recession declared this year — in part because the year is more than half over.11

But there’s nevertheless a degree of “fuck around and find out” to all of this. We’re seeing signs of slower growth (and faster inflation) in the hard data that was mostly only showing up in the soft data before12 — and the timing lines up conspicuously with when Trump escalated his trade wars.

Data denialism will do nothing to help Trump

I’m not sure exactly where firing the BLS commissioner ranks on the list of Trump-related outrages. Even if Congress does its job and McEntarfer is replaced with another competent successor, this could have a chilling effect on BLS and other government agencies to operate independently.

It’s also not surprising given Trump’s previous incursions on the independence of the Federal Reserve and other government agencies. This is the guy who sued a pollster for publishing results13 he didn’t like.14

Unlike in some other instances, though, I don’t see how there’s any real political gain for Trump in yet again undermining longstanding norms and institutions.

If the government’s jobs data is considered biased or unreliable, Wall Street will have other places to look. ADP reports figures on private payrolls, for instance. (And it also tells a bearish story: ADP showed a net loss of jobs in June, for instance.) Meanwhile, Gallup once tracked employment numbers on a weekly basis based on its large-scale surveys and could resume that effort. Or investment banks like Goldman Sachs might conclude they could have a competitive edge by tracking their own economic data.

However, this data is likely to be lower quality, because private organizations usually have lower response rates to surveys than the government does. And no longer having any reliable “ground truth” for major American economic data series will create more uncertainty for businesses and investors overall, which will discourage the sort healthy risk-taking that often fuels job growth. More generally, America benefits, particularly in our ability to borrow cheaply, from economic “soft power” in the form of being considered a reliable and transparent actor. Trump has eroded those foundations in his second term in a way he didn’t so much in his first, and I’ve been skeptical of the notion that markets will discipline him as much as others seem to assume.

Nor are job-seekers likely to be fooled. They can assess the situation for themselves based on their success at finding employment or the experiences of their friends and neighbors. The same holds, perhaps even more so, when it comes to higher prices, which are literally visible any time they go to the grocery store or drive past a gas station.

There is far too much belief among political types that voters’ views of the economy reflect narrative or spin, rather than being cross-checked against the ground truth they’re experiencing in their own lives. The Biden White House was also guilty of this, chalking up voter concerns about inflation to “misinformation” when low consumer confidence numbers not only highly understandable but also consistent with past periods of high inflation.

In the long run, reduced reliability of American economic data will not only harm the economy by increasing uncertainty for businesses but could also exacerbate the decades-long sense of negativity from voters in how the country is doing overall. Left to their own devices because they don’t think there’s any trustworthy authority, people are often biased toward thinking the situation is worse than it is. That could make life harder on incumbents trying to convince voters that the economy is healthy even when it really is.

But for now, Republicans are the incumbent party — and if you ask me, tariffs and an economic slowdown are a far bigger threat to Trump’s political capital than the distractions that often dominate the news cycle from day to day. We have more evidence now that the economy is slowing down, probably because of tariffs. And Trump’s actions on Friday suggest he’s scared to face the consequences.

I’m no longer a pickleball virgin.

This first step is very important. I’m currently working on a revised and improved NFL model for Silver Bulletin, and probably 80 percent of the work is in gathering, cleaning and QC’ing the data, whereas only 20 percent is actually the fun part of building out the logic of the model and testing empirical questions.

And tried to estimate it back to 1860 based on less complete information.

Say, I’m betting on an NBA game, one team looks extremely fatigued, and there are rumors that they were out at the strip club late the previous night.

About .18.

I guess if you wanted to play devil’s advocate, it’s also more likely that we’d have gotten the rate cut that Trump wants. But we’d have gotten a cut because the Fed correctly perceived that the economy was struggling.

Meaning, regardless of direction: there is little long-term directional bias in jobs revisions.

Reliable economic data in the U.S. generally dates back to World War II, so there’s nothing like Smoot-Hawley reflected in the dataset.

Outside of index funds, the only other thing I really do with my portfolio is weight it slightly toward some individual AI-adjacent stocks.

If the Trump administration is successful in reducing the number of people who come into the United States, that might lead to fewer jobs since many immigrants come here for work. But it won’t necessarily harm the unemployment rate if there are fewer overall people (including some who are here illegally) in the country seeking jobs. The White House, indeed, has highlighted the gains for native-born workers as compared to foreign-born ones. I don’t think “we’ll reduce immigration so much that the economy might go into recession” was necessarily part of Trump’s pitch for how he’d run the economy. But it’s a better attempt at spin than pretending that the recent jobs numbers look healthy on the surface.

The Polymarket contract specifies that the recession must be declared by December 31, 2025 or that there are two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth. Recessions are typically reported by the NBER with a lag of a few months, though. And the recent second-quarter GDP print was positive, although with some caveats. It wouldn’t be so surprising if it’s later determined that we entered a recession in the second half of 2025 — but we might not know it until next year.

Check out a data series I know well, for instance: Vegas tourism numbers.

Admittedly, highly inaccurate results.

The lawsuit has since been dropped.

It like you guys don’t even read the article and certainly don’t have a full understanding of how complex and vast the US economy is and the limits of forecasting and estimating employment for hundreds of millions of households given the timeframe and resources. Most likely it’s the typical MAGA mindset of if Trump is whining about it, it must be some horrible travesty without taking the time to actually understand the intricacies and details.

The report comes out the first Friday of the month, the economy is hundreds of millions of households, there is a tradeoff between precision and time as Silver discussed, how accurate can an estimate reasonably be given the resource and time constraints? The data is gathered from surveys with difficulties around response rate and sampling. The revisions months later have much more data in them from more sources. The final numbers have even more data and don’t solely rely of surveys.

Someone asked why release the early number if it’s has the most error in it? Because investors, businesses, and other decision makers would rather get a glimpse of what is happening in the short term, because despite the lack of precision the initial estimate does provide some value. It all comes down to understanding what the numbers mean, how they are derived, the underlying uncertainty in them. You don’t have to be an expert in statistical inference or Bayesian statistics to understand. You only have to break out of the strictly polarized view, not only see the black and white of the numbers are bullshit, it’s a conspiracy vs the numbers are god, worship them. The truth lives in the gray.

You mention zombie employment growth in the health sector. I wouldn't count on that. The trillion-dollar cutback in Medicaid and in ACA subsidies and changes in 340B ...will all close a lot of hospitals...putting a lot of folks out of work....and a lot of hospitals that don't close will endure service and staff constrictions, e.g., labor and delivery deserts (meaning no staff), ERs no longer operating 24 hours a day...no staff...you get the picture...Further, almost all small/rural hospitals will take a financial haircut and be unable to hire new/additional staff....and add in aging in the health sector.... Don't bet on employment growth