The McDonald's theory of why everyone thinks the economy sucks

Americans are spending as much of their paychecks as ever on fast food — and everything else.

Later this week, I’ll be publishing another subscriber Q&A. This is a feature for paid subscribers, and there’s still time for paid subscribers to submit questions (do it in this thread!). To sign up for a free or paid subscription for Silver Bulletin, you can use the link below.

I eat fast food.

Not often, but also not rarely. Maybe once or twice a month in a late-night munchies context. Maybe another couple times when I’m at an airport or something. And I don’t just eat at the highbrow “fast casual” restaurants like Shake Shack, although I like them. I am also well-acquainted with the Taco Bell menu.1

I wonder how often Jeff Stein and Taylor Lorenz — the authors of a recent Washington Post story on customer perceptions about the economy — eat from chains like McDonald’s and Taco Bell. I’m guessing it’s not very much.2 Because despite their attempt to frame consumer perceptions about high fast-food prices as “misinformation”, it’s in fact a category where there’s been a big increase in how much consumers are spending, and one that tells us a lot about why Americans are unhappy with the economy overall.

Here’s their story. An Idaho man posted a TikTok video of a McDonald’s order of a burger, fries and a Sprite that cost $16.10. What Stein and Lorenz want you to believe3 is that people are being misled by videos like these. The man ordered a “novelty item”, they say — a limited edition smoky double quarter pounder BLT (sounds yummy). But a Big Mac is much cheaper, they say:

The average Big Mac nationally as of this summer cost $5.58, up from $4.89 — or roughly 70 cents — before Biden took office, according to an index maintained by the Economist. That’s up more than 10 percent, but it’s not $16.

This is a weird and somewhat non-sequitur framing. For one thing, there actually has been quite a bit of inflation in Big Macs. According to the data they cite, Big Mac prices increased by 14 percent over the wo-and-a-half year period from December 2020 through June 2023. That’s not that bad compared to other goods and services; the overall consumer price index (CPI) increased by 16 percent over the same period. But, it’s still pretty high, and Big Mac prices had been fairly steady for years before 2020.

Also, since Stein and Lorenz are accusing consumers of falling for a cherry-picked data point — the Idaho man’s order — it’s worth noting that prices in the broader category of food away from home have grown faster than inflation overall, increasing by 18 percent over that window. It shouldn’t be hard to understand why people are unhappy about that.

That’s not the most important point, though. Instead, it’s something a little more subtle: people aren’t just paying more, they’re spending more. Put another way, they’re not just paying more for the same basket of goods — how the government defines inflation — they’re also putting more and more expensive goods in their basket.

Fast food is a perfect example of how this works. McDonald’s revenues, for instance, are going gangbusters. Same-store sales are up 8.8 percent globally and 8.1 percent in the United States. What’s driving the increase?

The company’s U.S. same-store sales increased 8.1%, fueled by strategic price increases. Executives said they expect pricing will be up about 10% for 2023, but third-quarter menu prices came down slightly. The chain also credited its marketing campaigns and digital and delivery orders for its sales growth.

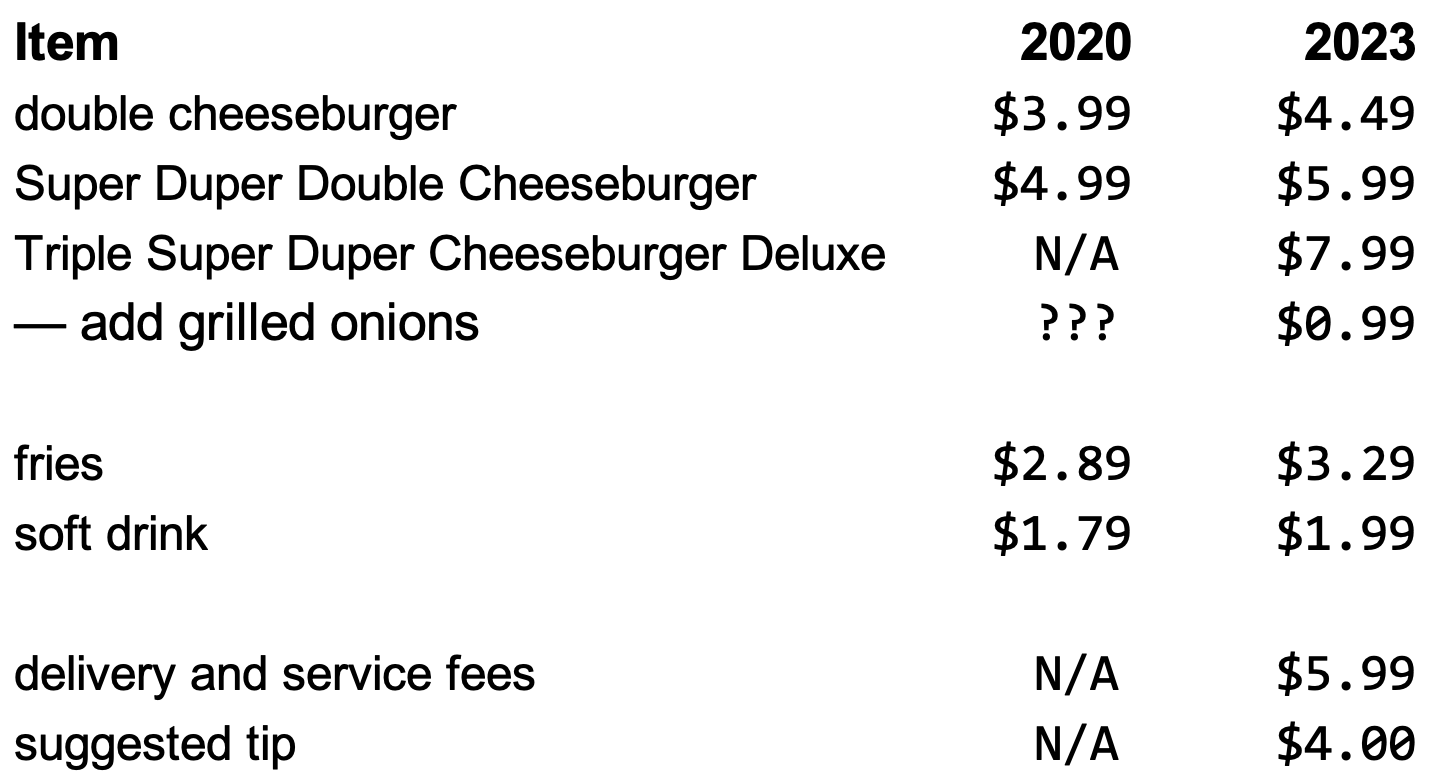

OK, so we have “strategic price increases”, “marketing campaigns” and “digital and delivery orders”. Let’s think through each of these by means of a stylized example of a fast-food menu. Here is my impression of what ordering fast food looks like in 2023 as compared with 2020:

Let’s say this chain offers a very limited menu: just burgers, fries and soft drinks. The inflation for their basic core product offering isn’t that bad. The cost of a double cheeseburger, fries and a Sprite has increased to $9.77 from $8.67, a 13 percent hike.

However, there are a lot of other things going on. First, this chain has made some strategic price increases. The price of its premium burger, the Super Duper Double Cheeseburger, has increased by 20 percent. That’s because this company has done some analytics — the high overall inflation of the past few years gave it a lot of data on how customers respond to price increases. It’s concluded that it’s profitable to engage in more price discrimination and customer segmentation; fast food is a budget item for some consumers, but others are quite willing to spend.

Next, after years of famously making no changes to its menu, this chain has introduced a specialty item, the Triple Super Duper Cheeseburger Deluxe. Technically, this is only offered for a limited time — the marketing department says that drives sales. However, it plans to nearly always offer some type of specialty burger. The company really likes these, because they anchor consumers to a higher price point. Even customers who don’t order the Triple Super Duper Cheeseburger Deluxe may now order the Super Duper Double Cheeseburger instead of the regular double cheeseburger.

Also, the restaurant now explicitly asks patrons whether they want to add grilled onions to their burger. Their grilled onions are great, but you used to have to be in the know and ask for them specifically. Now, most of the company’s orders are placed through electronic kiosks, or online, where the option is presented to customers directly. (These kiosks not only reduce labor costs but also increase sales because there are more opportunities to upsell customers — and customers may feel less embarrassed to add custom toppings and add-ons.) Also, the company has commissioned a clever viral TikTok campaign where hot influencers eat burgers with grilled onions, so there’s much better consumer awareness about them.

Finally, the company has a much more robust delivery program than it once did (remember, delivery is still relatively new for some of the major fast food brands) and tries to nudge customers toward delivery and takeout because these have higher profit margins. It may charge delivery customers higher prices for the same items, for instance. And even if it doesn’t, there are also lots of service and delivery fees. How these get split between the restaurant, the delivery service and the driver is often opaque, but there’s a lot of them to go around. When I tried just now to place an Uber Eats orderfrom a McDonald’s that’s just two blocks from me, for instance, it wanted $5.99 in service fees plus a suggested $4.00 tip on top of a $14 value meal order.

The point is simply this: it’s very easy to spend a lot more these days on fast food in ways that don’t necessarily show up in inflation data. Three years ago, I might have walked down the block and ordered a Super Duper Double Cheeseburger, fries and a Diet Coke for $9.67 before tax. Now, because Uber Eats and the restaurant have correctly determined that I’m lazy and they can price-discriminate against me and I fell for their viral marketing campaign, I’ll have them deliver me a Triple Super Duper Cheeseburger Deluxe with grilled onions, plus fries and a Diet Coke — at a price of $24.25 before tax.

And don’t think this experience — or the Idaho man’s experience — is atypical. Getting fast food delivered is pretty damned expensive. In-store, fast food can be expensive too if you start messing with upgrades, add-ons and speciality items. This is why McDonald’s revenues are still rocketing up even as inflation has slowed down.

But is fast food an atypical category — maybe one where companies are particularly good at price optimization or inducing more spending out of consumers? Not at all, really.

Let’s consider all consumer spending, which is captured by a category called personal consumption expenditures (PCEs). Basically, this is the sum total of how much American households spend in all categories in nominal dollars. In the chart below, I’ve compared the increase in PCEs with the increase in the inflation rate (the CPI) from December 2020 through June 2023, the same period that Stein and Lorenz considered for Big Macs:

Inflation — the price of a fixed basket of goods — increased a lot during this period: by 16 percent. But consumption increased by considerably more than that: by 25 percent. That’s right. From December 2020 through June 2023, Americans’ financial outlays increased by 25 percent. It’s not just that the fixed basket of goods was getting more expensive — they’re also putting more in their baskets.4

Now, it’s also true that consumption generally increases at a faster rate than inflation — as Americans get wealthier, they have more money to spend in real dollars. However, over the past few years, between higher prices for the same goods, clever strategies to get you to spend more, algorithmically-driven price discrimination, and pandemic-driven changes in spending habits — for instance, people who work from home are paying more for housing — Americans are really draining their batteries to zero. Here is the personal savings rate, which is now hovering at about 3 percent — about as low as it’s ever been save for a similar stretch just before the financial crisis.

I’m not sure that this is the whole story for why customer perceptions about the economy are so poor — this is a topic we’ll keep coming back to between now and the election. But I suspect it’s a lot of it. People are spending more money in real terms, a LOT more money in nominal terms, and the rate of increase is still fairly high (PCEs are up 6 percent year-over-year as of September). I’m wary of articles like the Washington Post story that frame politically inconvenient facts as “misinformation” — but this is an inconvenient set of facts for the White House.

I am thrilled that they brought back the Mexican Pizza.

Update: Stein eats Taco Bell a lot. Respect!

Or maybe I should say what the White House wants you to believe because the story is heavy with sourcing from the White House and Biden-friendly economists.

December 2020 is a slightly weird time for a comparison because it’s a point at which many economic activities were still constrained by the pandemic. But the same story holds if you use pre-pandemic data. From September 2019 through September 2023, the CPI increased by 20 percent but PCEs increased by 30 percent.

This reminds me of the argument I've read that people often complain about higher prices for houses without taking into account that houses today are bigger and offer more amenities than houses from decades ago. I've read similar arguments for car prices, where cars today are safer, more reliable, and have more features than cars from decades ago.

Great insight. I have some questions about the last part from a data perspective though.

1. The personal savings rate probably needs some kind of adjustment for demographics to be meaningful in this context. With boomers retiring in droves we should expect that number to be low right now. Does it still look low by historical standards if those effects are controlled?

2. You footnote the fact that the PCE-PCI chart has a weird starting date effect, but say the effect is still there measuring sept-2019 to sept-2023. That's fine, but we need a frame of reference since as you note PCE normally goes up more than PCI. So if it was 30% vs 20% over that period, what was it for say, 2014-2018? Given that the majority of the difference in your chart happens in *one* month out of the 24 months plotted, I feel like more investigation is needed on that one.