Twitter or Bluesky? How about neither.

Two fundamental problems constrain the business model of the “digital town square.”

I doubt that Elon Musk regrets his $44 billion purchase of Twitter in October 2022 — nor should he. Musk’s wealth and influence have only grown. It’s no exaggeration to say he’s one of the three most powerful people in the world right now, along with President Trump and President Xi.

And while Twitter — now officially “X” — probably isn’t the leading cause of the conservative vibe shift, its role isn’t nothing, either. Take a platform that many journalists and (ahem) thought leaders were utterly addicted to. Through a combination of algorithmic fingers on the scale and entry and exit among its user base — conservatives joining, liberals leaving — transform it overnight from being left-leaning to right-leaning. That’s going to have some downstream effects. As much as people might say they can decouple what they read on Twitter from real life, most can’t. Five years ago, journalists and Democratic Party leaders vastly overestimated how left-wing the electorate had become based on their Twitter interactions, resulting in severely miscalibrating their agenda. The positions Kamala Harris took during the peak of Left Twitter in ~2019-20 may even have cost her the election.

Of course, there are significant downsides for Musk. With X now contributing to a sense of giddy triumphalism on the right, the same overreach may now be happening in reverse.

Twitter’s business prospects have dimmed, too. Its advertising revenues are down sharply. And although there’s no perfectly objective way to assess its market valuation since the company is private, Fidelity valued X at $9.4 billion, less than a quarter of Musk’s purchase price, late last year.1

And yet, predictions of Twitter’s immediate implosion were embarrassingly wrong. The official reason I started this newsletter2, ironically, was because of widespread claims that Musk laying off most of the engineering staff could lead to a rapid loss in functionality. But while there have been a few glitches, the platform basically works like it always did. Some of Musk’s changes are even welcome. Making likes private is a good change: it’s fun to see when you get a little hidden blessing of approval from someone who, for ideological or business reasons, wouldn’t want to endorse your tweet publicly. Paying verified users for the advertising revenues generated by their tweets is a noble idea, even if the payments are relatively minimal3. The “For You” algorithm can lead you to some incredibly dark places if left to its own devices — plus a massive helping of Elon. But it can also be quite agile at surfacing content you want to engage with, positively or otherwise.

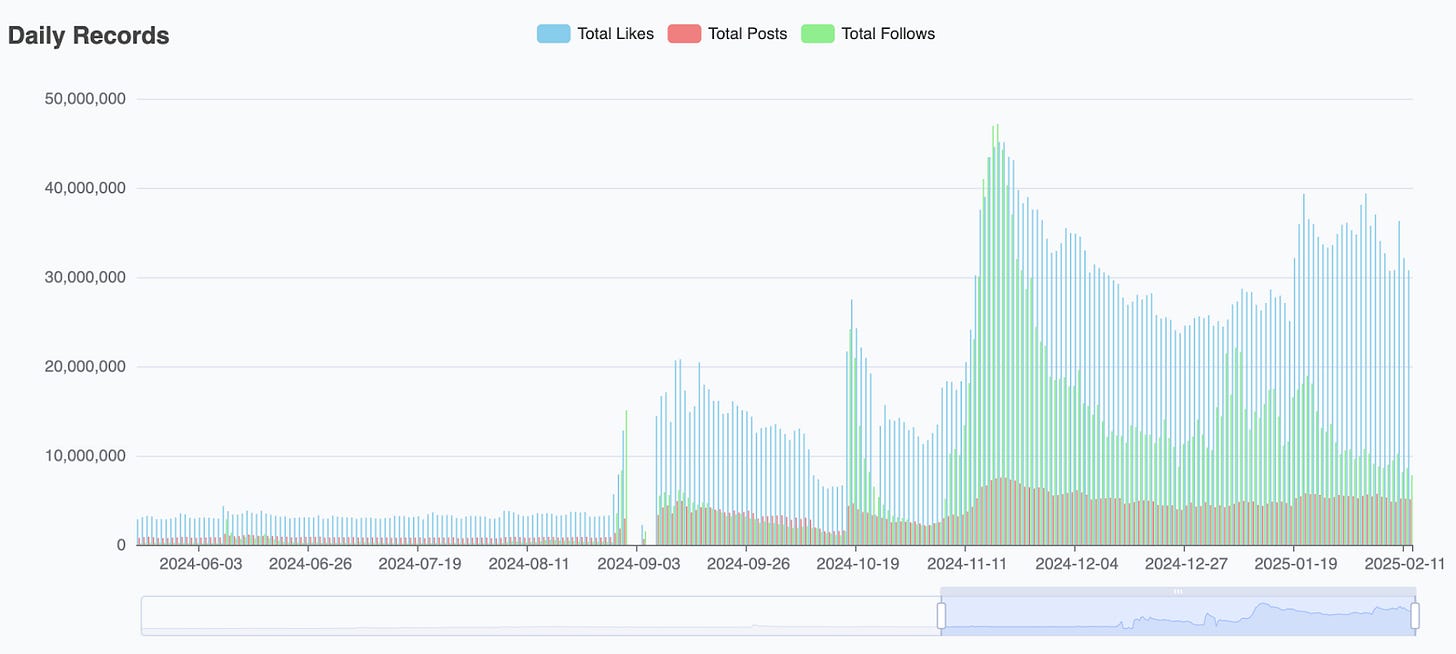

Moreover, alternatives to the platform haven’t really taken off. Meta’s X competitor, Threads, collapsed almost overnight. What about Bluesky, a spinoff originally created by former Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey? It’s found an audience on the left — but for now, it’s a relatively small one. Bluesky’s refreshing commitment to transparency leads to better publicly available data — but that data suggests its occasionally glowing media profiles are overstating its influence. Bluesky follows, likes, and posts surged after Trump’s election win but have since plateaued:

Nobody needs “microblogging”

The conventional wisdom is that if Twitter declines, some other “microblogging” platform will come along to gobble up its user base. But Twitter was never particularly successful as a business model. Meta/Facebook revenues outpaced Twitter by 24x in 2021, the last year of fully publicly disclosed data before Musk’s purchase. Based on Meta’s public filings and best estimates for X, the gap has now grown to 56x.

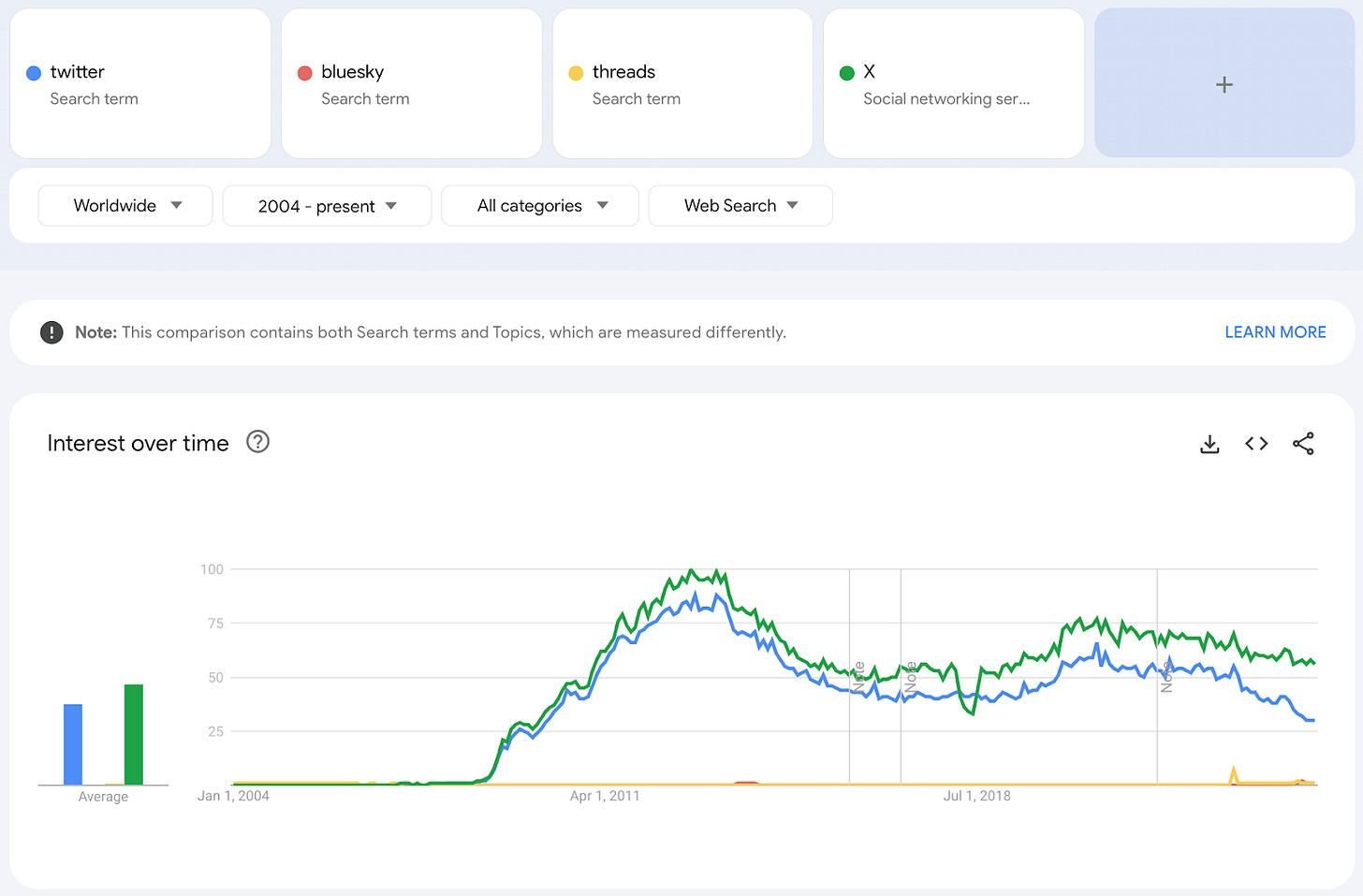

To be sure, with the affinity that thought leaders once had for the platform, Twitter has always had outsized influence relative to its user base or financial performance — that was presumably what motivated Musk to buy it (especially given that he tried to renege on the deal). Influence is more challenging to measure, but here’s one metric: the number of Google searches for “Twitter,” along with a Google Trends topic search for “X,” which in should include references to both Twitter and X. This data suggests that Twitter/X’s influence peaked in roughly 2012, about the time of Barack Obama’s re-election. There’s no particular bright line to demarcate Musk’s purchase of the company; Twitter declined in influence during Obama’s second term and has treaded water since. Still, Google searches for “Threads” and “Bluesky” barely even hit the radar by comparison.

Overall, these numbers suggest that Twitter’s influence has waned by about half relative to its peak, an estimate that passes the smell check with someone who’s been involved in journalism and content strategy for a long time — namely, yours truly. Losing half your influence from a high peak means you can still be a pretty big deal — I live near Madison Square Garden, and I’ll often see the names of bands on the marquee that are long past their peak and way “off trend,” but still performing to sellout audiences paying triple-digit ticket prices.

One frequent tweeter’s experience

This is not one of those posts where I promise to quit Twitter. (Nor am I joining Bluesky, at least not yet. Maybe it will eventually mature into a platform that’s more tolerant of viewpoints that are not in the leftmost 5 percent of America. For the time being, I’d rather stick a fork in my eye.) But I’ve engaged in some “harm reduction” to the point where — speaking of a decline from a high peak — I’m only checking it several times per day instead of constantly.

Having been a “trending topic” and Main Character on Twitter more times than you can count — rarely a good thing — my approach has become more utilitarian. I do more lurking than posting, and when I post, I want to get some tangible benefit out of it rather than share personal tidbits or engage in extended back-and-forths.4 Still, as Musk has throttled content to external links, it’s become less important from a business standpoint. Below is some data on the percentage of Silver Bulletin pageviews that originate from Twitter, divided roughly into quarters but with some breakpoints around the timing of our election coverage. The share of traffic originating from Twitter has declined from 28 percent in the first half of 2023 to just 2 percent so far this year5:

Meanwhile, I’m finding plenty of ways both old and new to replace the urge to be on Twitter 24/7. Substack, founded in 2017, is in the “new” category — full disclosure: I have a modest-sized investment in the platform — though it also recalls the Great Blogging Era from which FiveThirtyEight.com originated. I subscribe to a lot of Substacks, and I’ll typically find two or three meaty posts in my inbox in the morning that provide more nourishment than what I get from X. But there are also various homepages I frequent, from the New York Times to The Athletic — plus some old-school aggregators like Memeorandum. I don’t think I’m missing much, and I’m definitely improving my signal-to-noise ratio in encountering thoughtful content.

Twitter still has its virtues. It’s good for memes and jokes. It’s not bad for some of my "special interests," from poker to the NBA to AI. Although the quality of the discussion about polling and election forecasting on Twitter is terrible, it’s at least good for keeping track of new surveys as they come out. Its utility in breaking news situations has declined — but I think the extent of this is somewhat exaggerated just because it had such a clear lead over everything else before. And it’s basically a constant real-time hyperloop into Elon’s brain, which has value of its own if you’re covering politics.

My point is simply that there are good — indeed, often superior — substitutes for some of the use cases that Twitter or any other microblogging service provides — if not for everything. At the very least, X is not on a growth trajectory to becoming the “Everything App” or really on a growth trajectory at all. But other platforms have not gained influence as fast as Twitter has lost it.

The early and middle Twitter eras were probably outliers

I asserted earlier — I don’t think the point should be controversial — that Twitter was (and still is) disproportionately influential relative to the size of its audience and revenue generation capacity. How come?

Well, some of that is in the way that social media algorithms encourage addictive behavior. The endorphin hit you get from getting retweets and likes — or the adrenaline from posting something controversial. But this is true for any social media platform: Instagram, TikTok, you name it. What differentiated Twitter from those other platforms is that (i) it was primarily text-driven and (ii) it was very fast.

These are characteristics that play to journalists’ strengths. Say what you will about journalists — you’ll find plenty of media criticism in this newsletter. But having worked for the New York Times, ABC News, and ESPN, I know there’s still a crackle in the newsroom any time breaking news hits. Journalists take a lot of pride in forging the “first draft of history”.

Meanwhile, journalists are consummate “wordcels”. They — or really I should say we — are verbally gifted, quick-witted, and good at sensing conflict. The text-heavy, quick-reflex version of Twitter played to our strengths if it also inflated our egos and got us in trouble. We’re good with words — not necessarily with looking pretty on camera.

With that said, Twitter also presents problems for newsrooms. One is that the view of individual reporters can conflict with the voice of management or the institution’s editorial priorities. A journalist whose reporting might otherwise have gone through multiple rounds of editing can just Tweet It Out instead. Also, journalists aren’t the only creatures on Twitter, even if we once had those nifty verification badges. Elon was basically right that journalists and other experts don’t want to be in a constant battle for our authority or privileged status: the New York Times doesn’t want its official account to be on a level playing field with dogemaga42069.

In the Early Adopter Era (2006-2014), this wasn’t much of a problem. Twitter was fairly obscure. It was founded by tech nerds, and the other users were also basically nerds and news junkies. I don’t think the nerdy approach to life is perfect — but there’s generally something of a camaraderie among early adopters that often extends beyond ideological boundaries. News-loving nerds differ from the other types of people who argue on the Internet.

The Indigo Blob Era (2015-2021) presented a different configuration. As Twitter became more mainstream, early adopters encountered more trolls and partisans. But those partisans were mostly left-leaning, belonging to a particular college-educated tribe that most journalists also fit into. My Indigo Blob theory is that the partisans were running what in poker we’d call an “exploitative strategy,” trading on the good name of the media and other “trusted” (not really) institutions to advance a political agenda. They exploited journalists’ soft spots, especially their tendency to be left/liberal enough as to not want to be on the “wrong side” of sensitive issues, and their internal conflicts with younger, more progressive staffers.

Even if Elon had never come along to buy Twitter, the Indigo Blob Era may not have been sustainable. But in the Elon Era (2022-), journalists now face an owner who is incredibly adversarial toward their trade. Some media outlets have left the platform — and frankly, I’m surprised that more haven’t, given that Twitter was never a major driver of traffic or monetization.

But if Twitter and other microblogging platforms have declined in influence over the past few years, could a rebound be in order? Better management would help, and I’d argue that both Musk and the owners of Bluesky have sacrificed platform sustainability for existing in their own echo chambers. Still, there are two fundamental reasons why Twitter-type platforms will probably never be a great business.