SBSQ #5: The 5 types of people who argue on the Internet

Plus: Losing the biggest poker pot I’ll ever play – and some thoughts on the recent controversy about Substack.

Hey everyone, thank you for all the great questions for this month’s SBSQ (Silver Bulletin Subscriber Questions). Let’s keep it going: the ground rules are that these monthly threads are an opportunity for paid subscribers to ask me questions about pretty much anything. So you should submit your questions for February below – but you’re also more than welcome to comment on this month’s questions. To upgrade to a paid subscription, you can click on the button below.

For a “personal news” update, I’m mostly on track for the schedule I outlined at the beginning of the month. I’m basically on Mile 24 of the book-writing marathon. It feels really good, but I have a final substantive book chapter due to my editor at 9AM Monday morning. The following Monday morning, I owe Penguin a glossary and a brief mini-chapter that will slot somewhere in the middle of the book. At that point, the hard work will be done. In celebration or whatever-you-want-to-call-it, I’m planning to go to the European Poker Tour event in Paris in the middle of February (feel free to say hello if you’re around) but I’m generally good about blogging when I travel.

Bottom line: it’s not going to happen next week, but I expect posting here to ramp up to full speed by the end of the month. At that point, I’ll begin paywalling more posts, although I intend for the majority of articles to remain free. I do not yet know about the disposition of the election models and whether they will be public or private for 2024; those remain active conversations. I do expect to have some further announcements soon about the book and other things.

For this month’s questions, we’re erring on the side of “meta”:

Why do people argue on the Internet?

What are some good rules-of-thumb when making political contributions?

What do you think of the recent controversy about Substack?

What’s it like to lose the biggest poker pot of your life?

Did DeSantis just suck? Could any Republican have beaten Trump?

Why do people argue on the Internet?

Greg S. asks:

Matt Yglesias said that people seem to have a hard time understanding the logic and arguments of those they disagree with and that cultivating this ability to understand is a learned skill. I appreciated him saying that so plainly and feel this lack of skill in myself. Do you agree with his statement, how do you personally develop this skill, and what do you find gets in your way to prevent you from understanding others skillfully?

I’m a big Matt Y. fan — we met this summer for the first time in person (oddly enough in “Down East” Maine rather than New York or Washington). And I certainly don’t think it would be a bad thing if people were more precise when they argued. For me, having a lot of precision in sizing up an argument is just something I have a lot of practice with. It will not shock you to learn that I was a policy debater in high school. Poker involves a high degree of precision. Writing a book does, too — it’s not enough to just get the general gist of things if you’re hoping to write authoritatively on a topic.

But ultimately I’m reminded of the old Upton Sinclar line: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."

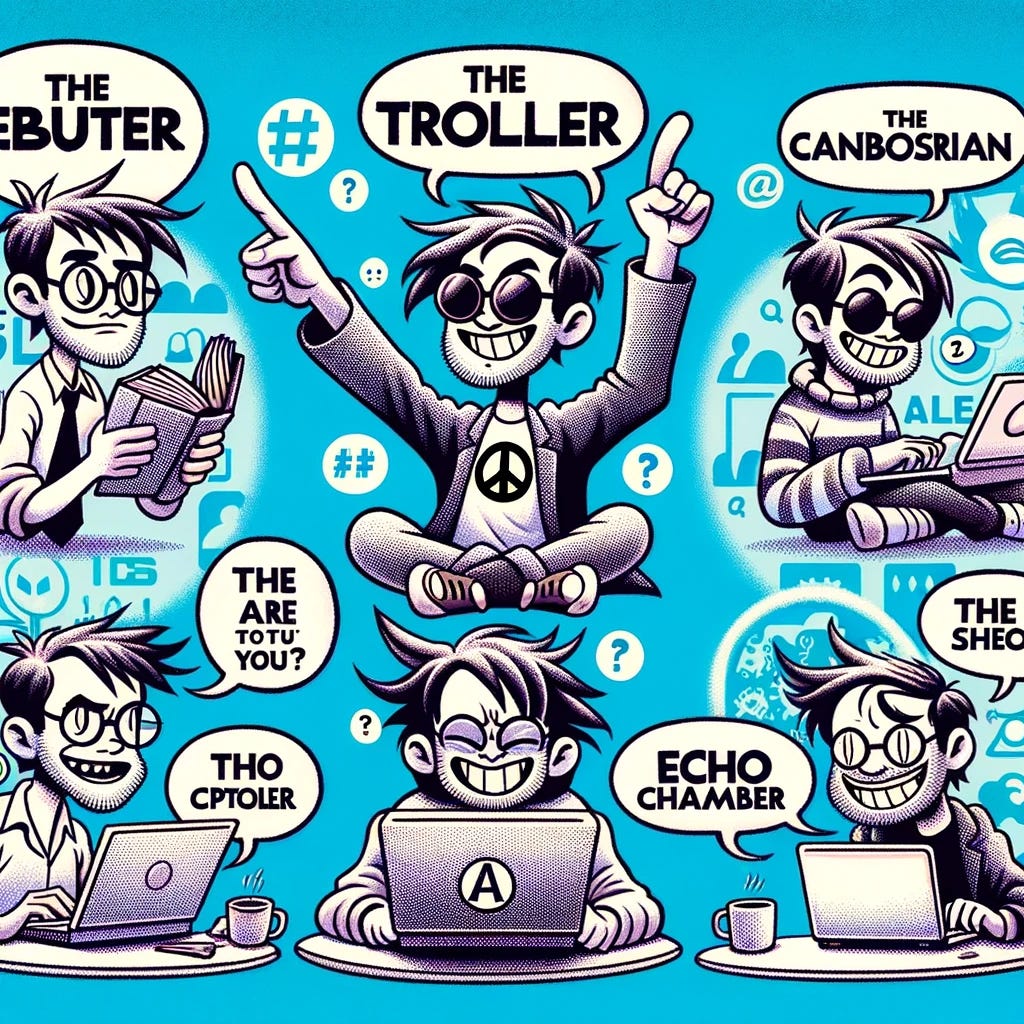

People argue on the Internet for all sorts of reasons, and relatively few of them benefit from high precision when articulating an opponent’s argument; people aren’t precise because they don’t need to be. You can break these reasons down into roughly 5 typologies:

Somebody Is Wrong On The Internet. This is named after the famous XKCD cartoon:

This is my typology — and Yglesias’s typology — or at least I’d like to think so. Maybe that’s flattering myself, but the description I’m going to provide isn’t entirely positive. There are some people who just can’t stand to let bullshit go unrefuted, just like there are some people who just can’t stand to see a crooked painting on a gallery wall. I do think this typology tends toward truth-seeking more than the other types and therefore benefits from high precision. A good indication of this is being willing to stake out unpopular positions, maybe not to a fault — I actually think there are vanishingly few true contrarians out there, but that’s another post — but at least some of the time.

But let’s be honest: there can be an element here of arguing for sport. People in this group tend to be highly competitive. Yglesias and I can both go into a lot of depth, but it’s not like everything we publish is a 2,000-word Substack article or a meticulously fair 7,000-word post with 32 citations on the Effective Altruism Forums. We also spar a lot with people on Twitter, which remains The Arena for Internet Arguments despite all the weird experiments that Elon Musk has performed on the platform. To be more precise, I wouldn’t say people in this group necessarily like to argue for arguments’ sake, but they like to be proven right by subsequent events or by forcing an opponent to expose that the premise of their argument is bullshit.

Country Lawyers. Let me use this trope rather than the “dispassionate truth-seeker vs. foaming-at-the-mouth activist” distinction (which gets some things right but is awfully reductionist). There are some people who, like a lawyer-for-hire in a one-stoplight town, stake out a position first and then do the best job they can arguing for it, even if their position intrinsically lacks merit and that’s become obvious to everyone. How do they choose these positions? Often it’s for ideological reasons although it doesn’t have to be. This is partly just a certain argumentative style, a misapplied heuristic of “never concede a point or let an argument go” even when it would be more persuasive to do so.

Incidentally, this is the style taught in high school policy debate. You’re randomly assigned either the affirmative or the negative side of a resolution, so you can literally be arguing against a policy in one round that you just argued for in the previous round. And at least in my day, it was considered to be a devastating concession to fail to respond to an opponent’s argument: an unrefuted argument, however silly, was presumed to be true. This is a terrible way to go about arguing in real life and creates all types of distorted incentives.

Country Layers are sort of the natural prey of Somebody-Is-Wrong-On-The-Internet types — the scissors to our rock — insofar as they tend to be extremely predictable. They’ll twist themselves into knots and often wind up making what amount to strawman arguments against themselves — better than the ones you could make up on their behalf. (Recent example: academics arguing that the Claudine Gay plagiarism accusations didn’t represent some kind of real academic misconduct even though they clearly did.) And yet, political movements benefit from having Country Lawyer types on their side — everybody needs a good attorney sometimes.

Flag-Wavers: Some months ago, I was being a typical Somebody-Is-Wrong-On-The-Internet type, arguing about some-or-another nonsense where I thought Democrats were being hypocritical. I don’t think it was the Lauren Boebert thing but let’s just use that as an example of an appropriately low-stakes controversy. An IRL friend of mine, first initial S. — someone who I lot of respect for, but we spar on politics a lot and he’s definitely to my left — was basically like “Hey man, don’t harsh our vibe here — we’re just trying to have fun, not everything has to be the Oxford Debating Society”.

It’s a fair point. Many people — probably the majority of people who argue about politics on the Internet on any given day, although not necessarily the majority of influential ones — are doing so primarily for recreational or hobbyist reasons, especially when it comes to minor, C-block on MSNBC controversies like the Boebert scandal. They are trying to have fun and signal to their tribe that they’re one of the Good Guys. Some of them are capable of serious political thought on more important issues, or at least have reasonably well-articulated priors, although others don’t.

But they’re not really trying to win arguments. Flag-Wavers are like the paper to us Somebody-Is-Wrong-On-The-Internet rocks; arguing against them is like punching a paper bag because they’re not really accepting our terms of engagement. To complete the cycle, they are susceptible to Country Lawyer scissors, however, because they can be drafted into adding manpower to an ill-advised argument.

#Engagement Baiters. I actually think this typology — “he’s just trying to get clicks!” — is less common than is usually asserted. Most people who argue about politics do so for some higher-minded reason, whether because they think they’re on the right side of big-picture questions or they think they have something intrinsically valuable to contribute.

But people who seek #Engagement above all else are out there. Telltale signs: they have a screencap of themselves on TV as their Twitter profile; they end every thread with “please buy my book!”; they often pick fights with more prominent accounts. The best #Engagement Baiters are skilled trolls, but others have carved out a more specialized ecological niche, including being willing to be primarily publicly identified as a hater of some more accomplished person.

It is, of course, usually a bad idea to pick a fight with an #Engagement Baiter. They have a lot of time on their hands and will spend an inordinate of it writing 13-post Twitter threads where they make one or two arguably good points along with a lot of filler and bullshit, hoping that nobody will check their work — or not really caring so long as people pay attention to them.

Certifiable Outright Lunatics. Did you know that some people are literally crazy? OK, that’s not a medically precise term. But there’s a lot of profoundly unhappy people in the United States. And then there are people who are not merely unhappy but have some sort of unresolved trauma. It’s somewhat taboo to talk about — although Scott Alexander recently went there — but arguing on politics on the Internet is potentially a dangerous thing for people like this. It can aid and abet narcissism or a persecution complex, and it can provide a veneer of Fighting The Good Fight to rationalize compulsive or antisocial behavior.

I don’t know exactly what percentage of people fall into this category. But somewhat like with slot machine addicts — relatively few people get addicted to slots, but addicts make up a high percentage of people playing slots in any given casino because they play them so often — a high percentage of the most toxic behavior comes from this group. You just have to understand that if you argue on the Internet, you’re going to encounter crazy people — again, not a medically precise term — not just occasionally but often. Certifiable Outright Lunatics often band together, too; misery loves company.

And here’s the thing; it’s not merely important to avoid arguing against Certifiable Outright Lunatics — it’s also important to avoid arguing with them. In other words, you do not want to amplify a Certifiable Outright Lunatic even if they’re on your side on a particular issue. They are the most prone of any of the typologies to suddenly switch sides, but the crazy never goes away. Block, mute, ignore, and hope they have some people in their lives who love them.

All right, that was a long answer, so let’s go through the rest of this month’s questions in lightning-round style.

What are some good rules-of-thumb when making political contributions?

Zach asks:

Question: is donating money effective? I know you have included donations in election models as a signal for support, but would you recommend doing it yourself? Imagine you care a lot about the outcome of the next election and can afford to donate some money. Is it worth it? Would you donate money to the presidential race or to down ballot races? To candidates or to organizations?

Quick answer: donate to anything except major-party presidential, U.S. Senate and gubernatorial campaigns. (In the general election at least; contributions are sometimes more worthwhile in the primaries.) Those candidates are generally already flush with cash.

In fact, diminishing or even negative returns on additional campaign spending can be an issue whenever a candidate raises a disproportionate amount of money relative to their number of constituents. (See also: Sam Bankman-Fried’s disastrous efforts to back an effective altruist candidate in an Oregon Congressional primary last year without the candidate’s consent; I have some amusing stories about that in the book.) As a rough rule of thumb, anything more than ~$10 per potential voter is incredibly excessive; voters may feel so oversaturated with advertisements and campaign literature that it backfires. Donate to downballot candidates, causes that you care about or effective charities instead.

What do you think of the recent controversy about Substack?

Nick Boonstra asks:

I can only assume this will be part of your "misinformation" post, but apparently we're sharing this platform with Nazis, and Substack is letting it ride. Would love your thoughts/feelings on that. Fwiw I tend to agree with your free marketplace of ideas take, which I can feel uncomfortable voicing but do feel strongly about. If manufactured news stories on Facebook were truly enough to sway the outcome of the 2016 election then I am far more concerned about the American public at large than I am about any sort of foreign interference -- people need to do better about what they will and will not believe. But that may just be a nice thing for me to believe. I don't plan on taking my newsletter off the platform any time soon, but then again that's hardly a drop in the bucket. Would love your thoughts.

OK, this is definitely a paywall question. Although I’ll warn you that I’m going to be pretty circumspect in answering it.