It's easy to screw up on breaking news. But you have to admit when you do.

This week brought another self-inflected wound for trust in journalism.

I worked for the New York Times for three years between 2010 and 2013, during which time I was frequently in its handsome offices on Eighth Avenue in Manhattan for breaking news events. Mostly by that, I mean election nights, though I went through spurts of working from the office on other days, too. Whenever a breaking news story hit, or something unexpected happened — say, a surprise winner in a presidential primary — there was a crackling of excitement in the newsroom as headlines were redrawn, evening plans were scrapped, and reporters read aloud their rewritten lede paragraphs to one another.

This is going to be a weird analogy, but I went to Hawaii some years ago, and at one point I saw an active volcano that was — at that moment slowly and safely — burping lava into the Pacific Ocean. Holy shit, I thought to myself. It was literally forging new land, changing the shape of the Pacific coastline, and I was there to watch. That’s roughly what it felt like on nights like those at the Times. I was watching the news be forged at the most influential newsroom in the world.

I like the lava analogy because it suggests you are dealing with fluid material that is hardening into something more permanent — narratives, the conventional wisdom, established “facts”. In the metaphor, the New York Times is not the volcano itself — the cauldron is the news. Rather, the Times’ editors and reporters are like a team of engineers or Department of the Interior employees who are trying to redirect the lava flows — maybe to keep them away from populated areas or to serve some other objectives. Their decisions have big, even permanent consequences.

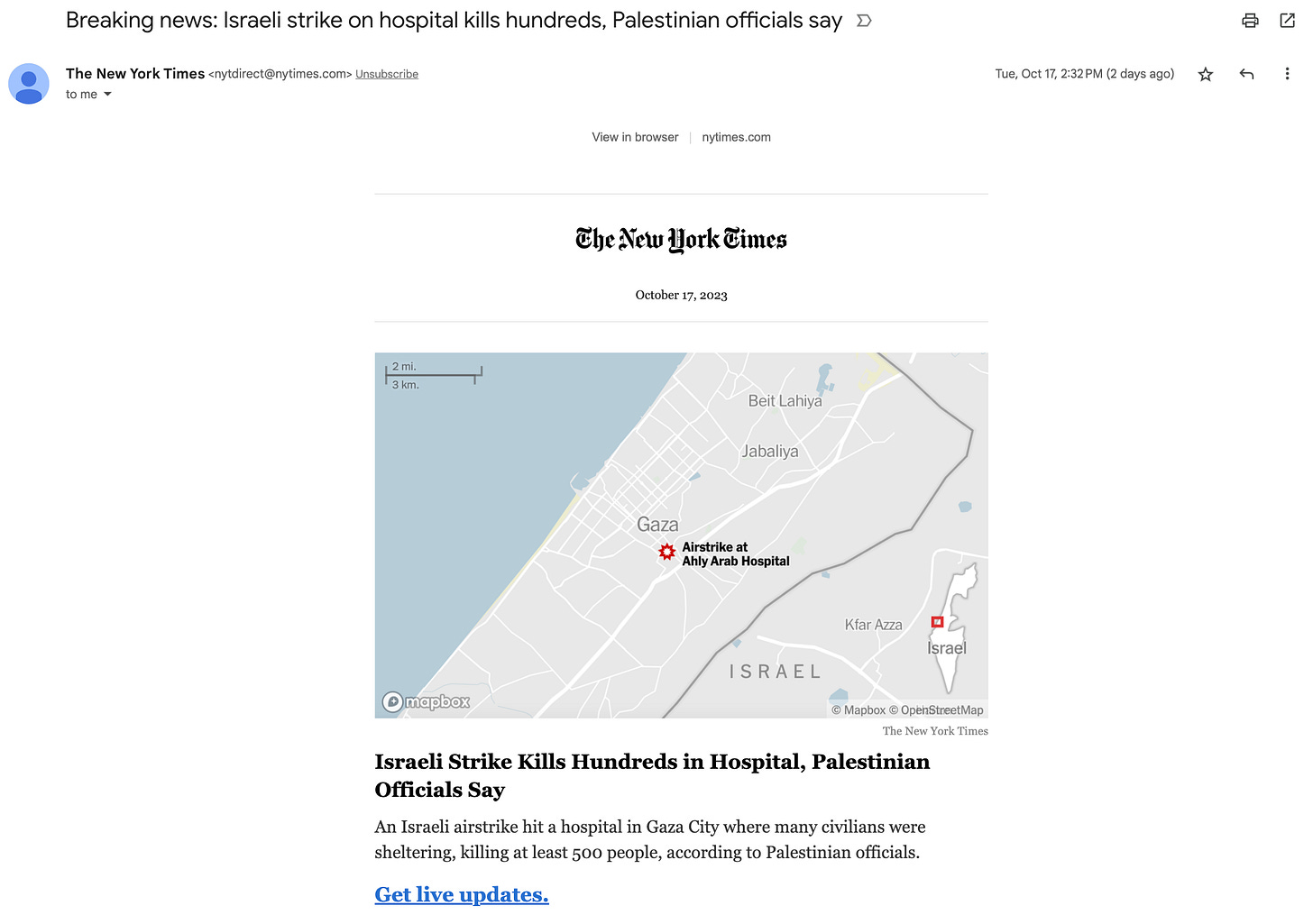

On Tuesday night local time — Tuesday afternoon New York time — there was an explosion near a hospital in Gaza City. At 2:32 p.m. the Times sent subscribers like me the following news alert:

In case you can’t see that image, the headline reads: “Israeli Strike Kills Hundreds in Hospital, Palestinian Officials Say.”

Almost every word of that first clause is now disputed. The Israeli Defense Forces said that the blast was the result of a misfire from a Hamas rocket, and President Biden, citing Department of Defense evidence, has backed that claim. Also, the explosion appears to have hit a parking lot adjacent to the hospital, not the hospital itself. And it remains unclear what the death toll was — but forensic evidence doesn’t seem to be particularly consistent with a three-figure number. I’m sure you can find better summaries of the various claims and counterclaims elsewhere; I’m deliberately trying to be circumspect as I make a broader point about the news business.

And the point is this: that lava is dangerous. It’s hot. It’s tempestuous. And in breaking news situations, it’s moving fast. In a post on Twitter, I estimated that dealing with situations where the news is evolving over the course of minutes or hours is about 10x harder than ones where it develops over days or weeks. I mean that literally. I hate to play the “lived experience” card — there are many journalists who have much more experience in breaking news situations than I do — but handling these cases is a very difficult job, much more difficult than armchair quarterbacking like I’m doing now.

Shouldn’t newsrooms just be more careful in these situations? The short answer is “yes”. The Times’s excuse is basically that it was just passing along a newsworthy claim made by a Palestinian spokesperson. I don’t think that really works, however.

Sure, technically, the claim in the Times news alert was attributed. “Israeli Strike Kills Hundreds in Hospital, Palestinian Officials Say” (emphasis added). But that’s not how most readers see it, particularly when the attribution comes at the end of the sentence. They’ll see ISRAELI STRIKE KILLS HUNDREDS IN HOSPITAL (palestinian officials say). The Times is providing some degree of dignity and veracity to that claim by printing it, just as it would if it sent out a breaking news alert that said:

“U.F.O. Cited Over Manhattan, Nate Silver Says”

If it later turned out that the “U.F.O.” had just been a 747 landing at LaGuardia, and I’d made the claim while tripping on psychedelic mushrooms, this wouldn’t really absolve the Times for printing it without some independent verification or a second source.

But, newsrooms do face conflicting pressures. They will get criticized if they’re too slow on reporting the news. Or they may fear — I’m explaining their thought process, not endorsing it — that failure to report on the story will create a news vacuum that will be filled with “misinformation”, partisan sources, or random people speculating on Twitter.

And it is possible to screw up in both directions. Fearing a repeat of election night in 2000, when the state of Florida was prematurely called twice (!) by the networks — it’s still amazing that didn’t do even more damage to journalistic credibility — most newsrooms are now very cautious about declaring winners in elections. I thought that they actually erred too much on the side of caution in 2020, for instance, when it had become obvious at least 48 hours before the networks called the race that Biden was eventually going to secure enough votes to win Pennsylvania and other key Electoral College states.

When a newsroom misreports a breaking story, does that reveal its editorial biases? Again, the obvious answer is “yes”, but I’d qualify that by saying it reflects the thought processes of the particular people who were on hand to make decisions at that particular moment. News that breaks at night, on the weekend, or in the midst of another developing story probably needs to be treated with even more caution. Until the AI singularity takes place — just kidding — the Times and other newsrooms will be staffed by error-prone human beings.

In the light of day, however, the media has far fewer excuses for getting the story wrong. And although the Times eventually walked its initial reporting back, it was exceptionally stubborn about doing so. At 5:04 p.m. on Tuesday, it sent out another news alert: “Israel and Palestinians blame each other for Gaza hospital blast”. At 6:01 p.m., yet another —“The Evening: A blast killed hundreds at a Gaza hospital” — that treated the causality figure and the location of the blast as a hard fact.

Even at 9:43 a.m. on Wednesday morning, the Times was still running with this headline on its mobile edition:

By this point, other news outlets had begin to substantially change their framing of the story. This was the Wall Street Journal at the same hour, for instance:

In a business section article, the Times later addressed the controversy in disingenuous fashion. The headline, framed in the passive voice, tells you pretty much all you need to know: “After Hospital Blast, Headlines Shift With Changing Claims.” There is no admission of error whatsoever:

The news changed quickly over a couple of hours. Many Western news organizations, including The New York Times, reported the Gazan claims in prominent headlines and articles. They adjusted the coverage after the Israeli military issued a statement urging “caution” about the Gazan allegation. The news organizations then reported the Israeli military’s assertion that the blast was the result of a failed rocket launch by Palestinian Islamic Jihad, an armed group aligned with Hamas.

In this account, the Times frames itself as an innocent, passive actor, one that’s merely reporting on the existence of the lava — neglecting its role in trying to steer it. That’s complete bullshit, because the Times is extremely and often somewhat proudly self-conscious of this role. “We set the agenda for the country” is literally the prevailing attitude in the building.

And yet, the reporter on the business section story couldn’t even get a comment from an editor in the Times newsroom. She had to rely on the PR department instead:

The BBC and Al Jazeera did not immediately respond to a request for comment. A Times spokesman said, “We report what we know as we learn it.”

This morning, Gallup published its annual poll on trust in the media. Overall, only 32 percent of Americans say they trust the mass media “a great deal” or “a fair amount” to “report the news fully, accurately and fairly” — tied with 2016 for a record low.

The standard rebuttal in the Indigo Blob is to blame some combination of Republicans, misinformation, social media and political polarization for the decline, and there’s some truth to each of those claims. But some of it is the media's own damned fault.

I've limited comments on this post to paid subscribers after 5 of the first 6 were, shall we say, not constructive. May just have to turn them off entirely.

747s can’t land at LaGuardia, by the way. So one landing there would still be news, though significantly less newsy than a UFO. 😉