How culture trumps economic class as the new political fault line

It's not just the economy anymore, stupid.

Despite being an econ major, I mostly write about politics. Especially in election years. But in 2012, the most important political event of the campaign was an economic data release. It came at 8:30 a.m. on the first Friday1 of every month: the jobs report — more formally known as the “Employment Situation Summary” — which articulated the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ estimate of how many jobs had been created or lost. The jobs report was a focal point for the election, serving as a referendum on whether the economy had recovered enough from the Global Financial Crisis to warrant a second term for Barack Obama. It almost always created banner headlines — and sometimes even dubious claims about the reliability of the numbers.

Did voters really care, or was this just a media fixation? Well, that’s often a chicken-and-egg problem. After years of understating the influence that media coverage has on popular perceptions of economic affairs, the conventional wisdom has shifted too far in the other direction in not giving voters enough credit for being able to divine economic conditions on their own. “Vibes” are overrated, in other words.

In fact, if you polled voters in 2012, they shared the media’s laser-focus on the economy. In Gallup polling, around 70 percent of voters brought up the economy when asked an open-ended question about the most important problem facing the country. Only about half as many voters do so now, and that was true even when inflation was at its highest levels in decades in 2022. Although the economy still qualifies as an important concern, it competes with many other things — from abortion to immigration to the War in Gaza to Donald Trump’s various trials — for public and media attention.

Economic voting theory is overrated

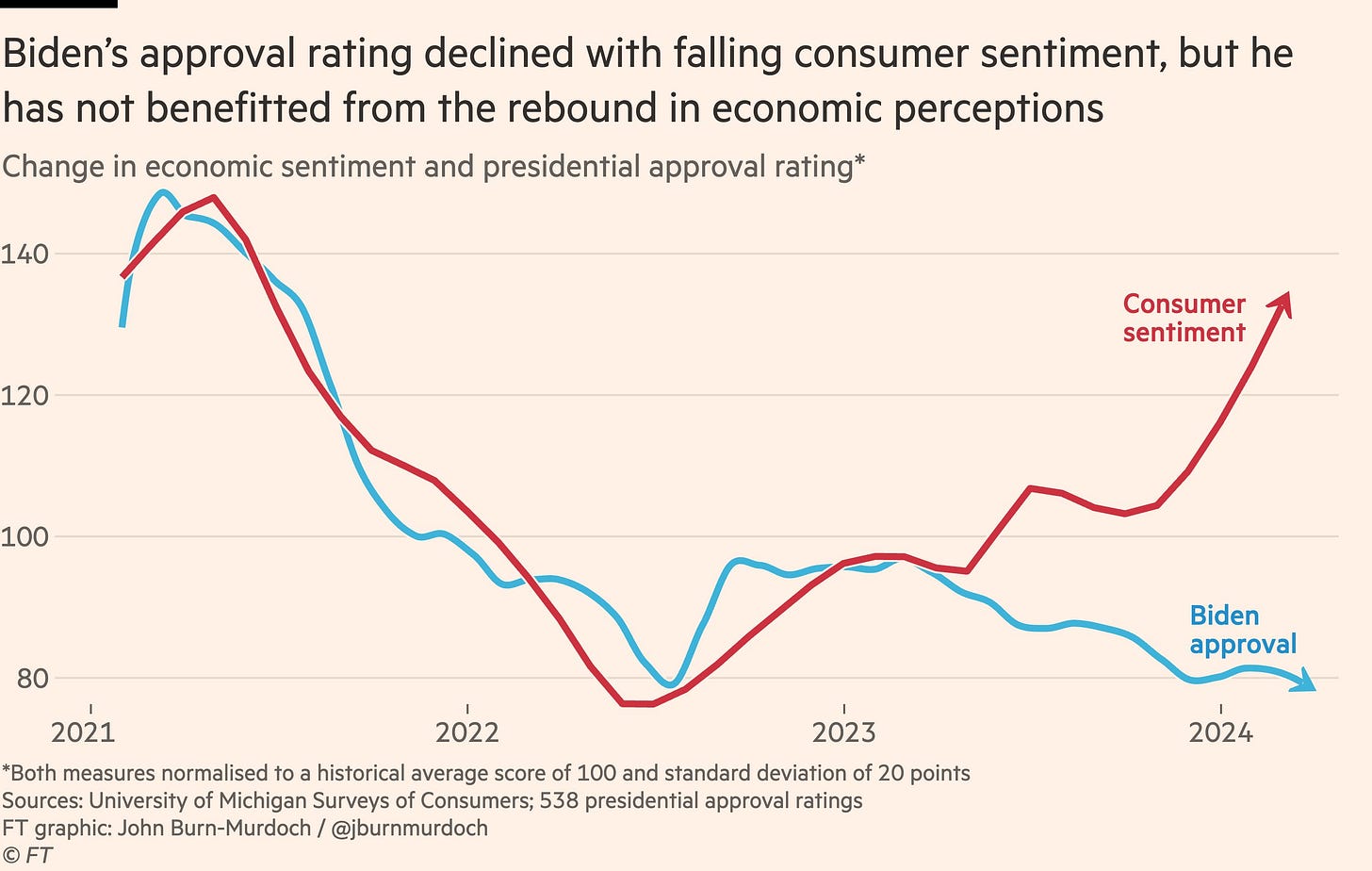

It’s in this context that I’ll bring up a fact that Democrats are understandably concerned about. Even as consumer and investor sentiment has improved, President Biden’s approval rating hasn’t, or at least it hasn’t by much:

Now, let me roll out a small truckload of caveats. First, we still have a long way to go until the election. Biden has more than seven months to make his case, and there’s perhaps — perhaps! — been some improvement in his numbers lately.

Next, the relationship between the economy and elections is sometimes overstated. So-called economic voting theory, in which voters “rationally” assess the condition of the economy to evaluate the incumbent party’s performance, was once the province of political science, a way for data nerds to tweak the pundits by claiming that voting results were highly predictable months in advance. In fact, the nerds were mostly wrong about this. Economic voting theory relied on a lot of bad science, methods that tortured the data and overfit models on small sample sizes.

I know I sound flip about this, but I’ve possibly spent more time analyzing the effect of the economy on American presidential elections than any person on Earth — in 2012, I became absolutely obsessed with the problem. Looked at more carefully, and over a longer time period, the relationship between the economy and the incumbent’s performance is positive, but noisy. “The incumbent wins when the economy is good” is a useful, weak prior, but not an iron law, and one that historically has had many exceptions. It’s also not clear that economic voting is really so rational at all, given that presidents have relatively minimal impact on the economy and that the rational thing when selecting a president for the next four years is to project future performance, not reward or punish him based on the past.

It’s more accurate to say that the economy is usually on the list of prominent concerns for voters. Look, Biden definitely wants the economy to continue improving. When I release this year’s election model2, it will include the economic prior, as it has in the past. But the extent to which the economy outcompetes the other concerns varies from election to election. And it wouldn’t surprise me if that concern is on a downslope because of how the class politics of the United States are changing.

A not-so-brief history of presidential voting by economic class

The political class doesn’t talk about economic class all that much; it has gone out of vogue. Partly that’s because class has been replaced by concerns about race, gender and sexuality in progressive critiques of the status quo. And partly it’s because the class politics of the political class are awkward.

Here’s one complication. Over the past two decades, there’s been a political realignment in the United States along educational lines: college graduates mostly vote for Democrats, and “noncollege” voters mostly vote Republican. But Democrats have also long relied on Black and Hispanic voters, and those Americans remain less likely to complete college — which may help to explain why Democrats’ standing with Black and Hispanic voters is eroding.

Also, educational attainment is correlated with income. But this gets weird, because more schooling historically predicts Democratic voting, while higher incomes historically predict voting GOP. To get a more visceral image of this, think of a person with low education but high income. I’m coming up with a high school graduate who became successful in some business venture, like running a car dealership or a local real estate empire. That type of voter reads as very Trumpy. Conversely, think of someone with high educational attainment but low income — I think of a recent PhD working as a barista or college test prep counselor or as an adjunct professor somewhere. You’d expect them to be a strongly Democratic voter with lefty politics and a Mastodon account.

Many journalists and other intellectual types also fall into this group: high education, middling incomes. But they’re often adjacent to creative class types who are in fact doing quite well for themselves. A fledgling journalist with $80,000 in student loan debt working for a doomed-to-fail digital media startup is nominally on the same side of the culture wars as a Hollywood producer worth $80 million — and her rich “socially liberal” publisher. But their economic interests don’t really align.

So for the rest of this article, I’m going to focus on economic class, using class rather than race or education as the through-line for measuring changes in party coalitions. I don’t mean to suggest that this is the only lens through which one might look at the electorate. But it’s a revealing one because it suggests how much the parties have changed.

Let’s start in 1976, which is the first election with semi-reliable3 national exit polling and also a close contest between Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford. Here you see that the party coalitions are near mirror-images of one another. Carter won 62 percent of the two-party vote (that is, excluding votes for third parties) among the poorest voters, while Ford won 62 percent of the wealthiest voters.

Carter, of course, was not long for the Oval Office, in part because of the energy crisis and high inflation of the late 1970s. Where did Ronald Reagan make his gains? Well, among everyone, pretty much; he blew Carter out of the water. But his improvements were larger among the wealthiest voters, befitting his brand of trickle-down economics.

In 1984, after overcoming another recession in 1981-82, Reagan won re-election by an even wider margin amid high GDP and jobs growth and falling inflation. And this election actually reduced class polarization. Reagan didn’t do particularly well among the very poorest voters, who often rely on unemployment insurance, Social Security or other firms of fixed income that Republicans often seek to cut. But he made major gains among the lower-middle working class, winning 58 percent of voters who earned between $12,500 and $25,000 that year:

I’ll return to Reagan at the end of this story. But next up is George H.W. Bush, who in 1988 won a third straight term for Republicans but represented more of a reversion to the class-politics trend. Bush lost ground relative to Reagan with poor and working-class voters, while holding up well with the richest ones.4

Bill Clinton in 1992, like Reagan in 1980, made gains in every income group. But unlike Reagan, he did particularly well among the poorest voters, winning 72 percent of the vote from those earning under $15,000 per year. So class polarization was as strong as ever. Democrats could still honestly describe themselves as the party of the working class.

It’s mostly the same story in 1996. Clinton’s standing eroded a bit among the very poorest voters, perhaps because of his welfare reform bill, conspicuously signed right in the middle of campaign season. But he gained further ground among the group of voters just ahead of them on the income ladder earning between $15K and $30K a year:

2000 is when we begin to see a notable decline in class polarization. George W. Bush used a combination of tactics — an appeal to the religious right, relatively high numbers among Hispanics, and branding Al Gore as an out-of-touch elite — to perform competitively well with poor and working-class voters and win the Electoral College by the thinnest possible, much-litigated margin of 537 votes.

Class polarization rebounded in 2004 — an election John Kerry came closer to winning than many people remember — perhaps because the wealthy rewarded Bush for his tax cuts. Bush, of course, continued to exploit “family values” politics and Karl Rove credited Bush’s win to Bush’s opposition to gay marriage. But that message didn’t necessarily sell so well among the poorest voters, who were growing increasingly concerned about the Iraq War. (This was less of a concern for the wealthy, who are the least likely group to send children to the military.) Instead, 2004 was a good election for economic voting theory, with the economy solidly in recovery after the recession of 2001.

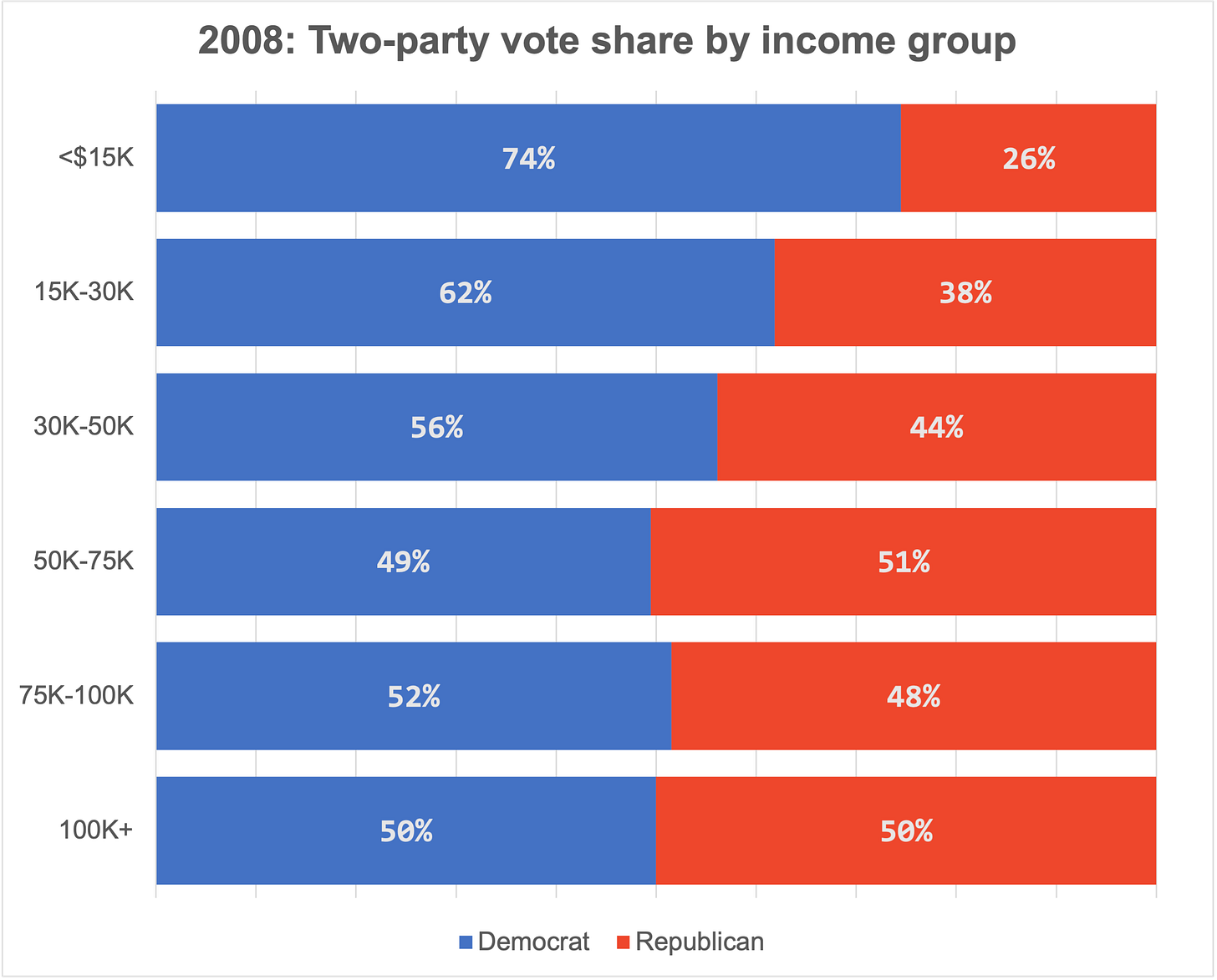

Although Barack Obama, like Gore and Kerry, was portrayed by Republicans as an elite, he did extremely well with the very poorest voters, even better than Clinton. This is partly because many poor voters are Black or Hispanic, and Obama had a lot of appeal both to these groups as the first nonwhite major party presidential nominee. He also did fantastically well among college students and young voters, who often have little income. Now, this story is complicated by the fact that Obama was also popular with elites — he split the wealthiest voters evenly with John McCain, something unprecedented for a Democrat. McCain’s strongest group was actually “middle-class-plus” voters who earned $50K to $75K per year:

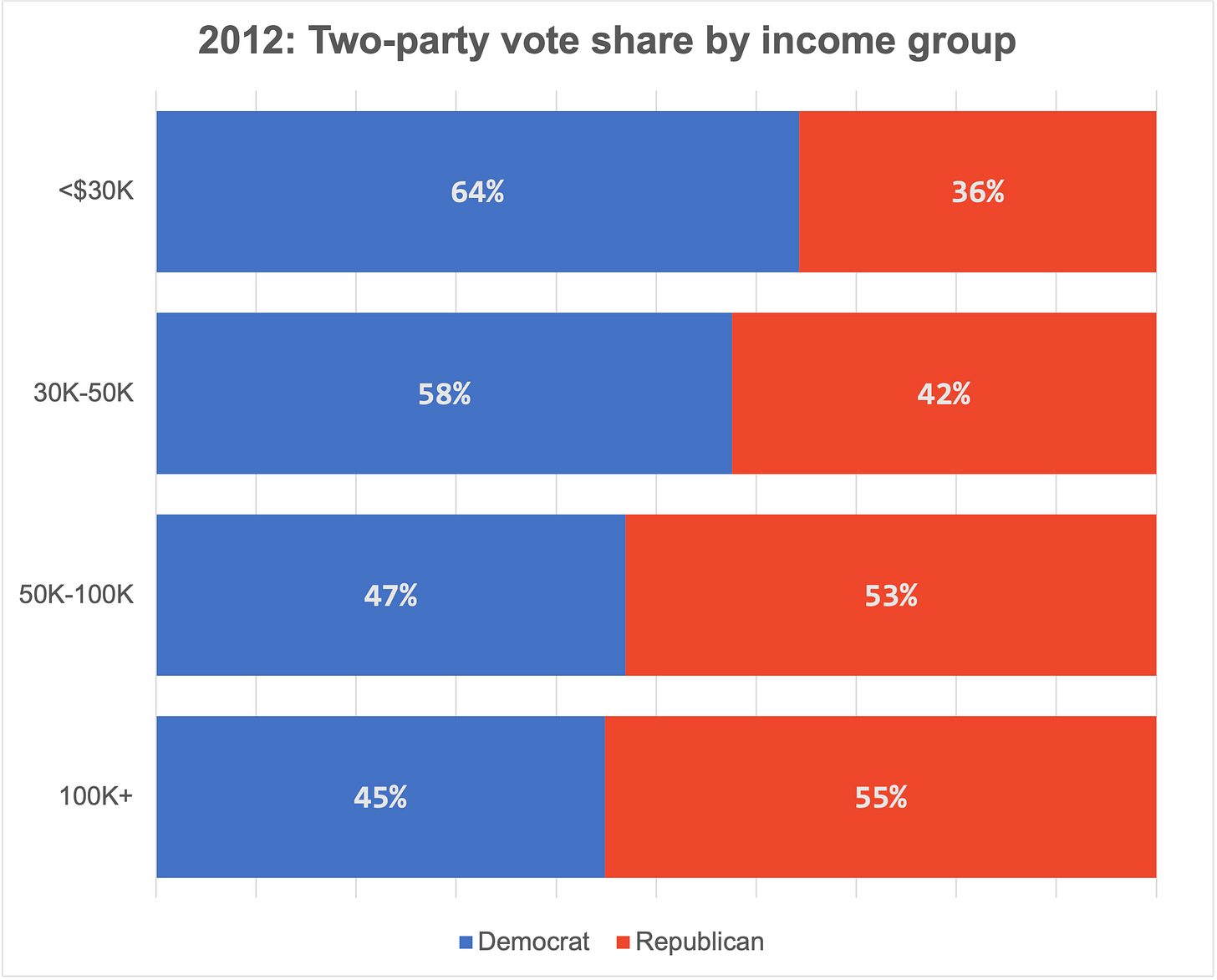

Now we’re on to 2012, where we unfortunately lose some fidelity in the data because the exit poll tracked only 4 income categories rather than 6. (There’s no longer a breakout for voters earning less than $15K annually, for instance.) Still, this is about what you’d expect: Mitt Romney won back some of those traditional GOP high-income voters, but did no better than McCain among the rest of the electorate. Maybe you can attribute that to the Obama campaign successfully portraying Romney as an out-of-touch elite and/or rapacious capitalist — Obama 2012 was one of the better-run campaigns, if you ask me. But this is also another decent election for economic voting theory; those jobs reports down the stretch run of the campaign were mostly pretty good.

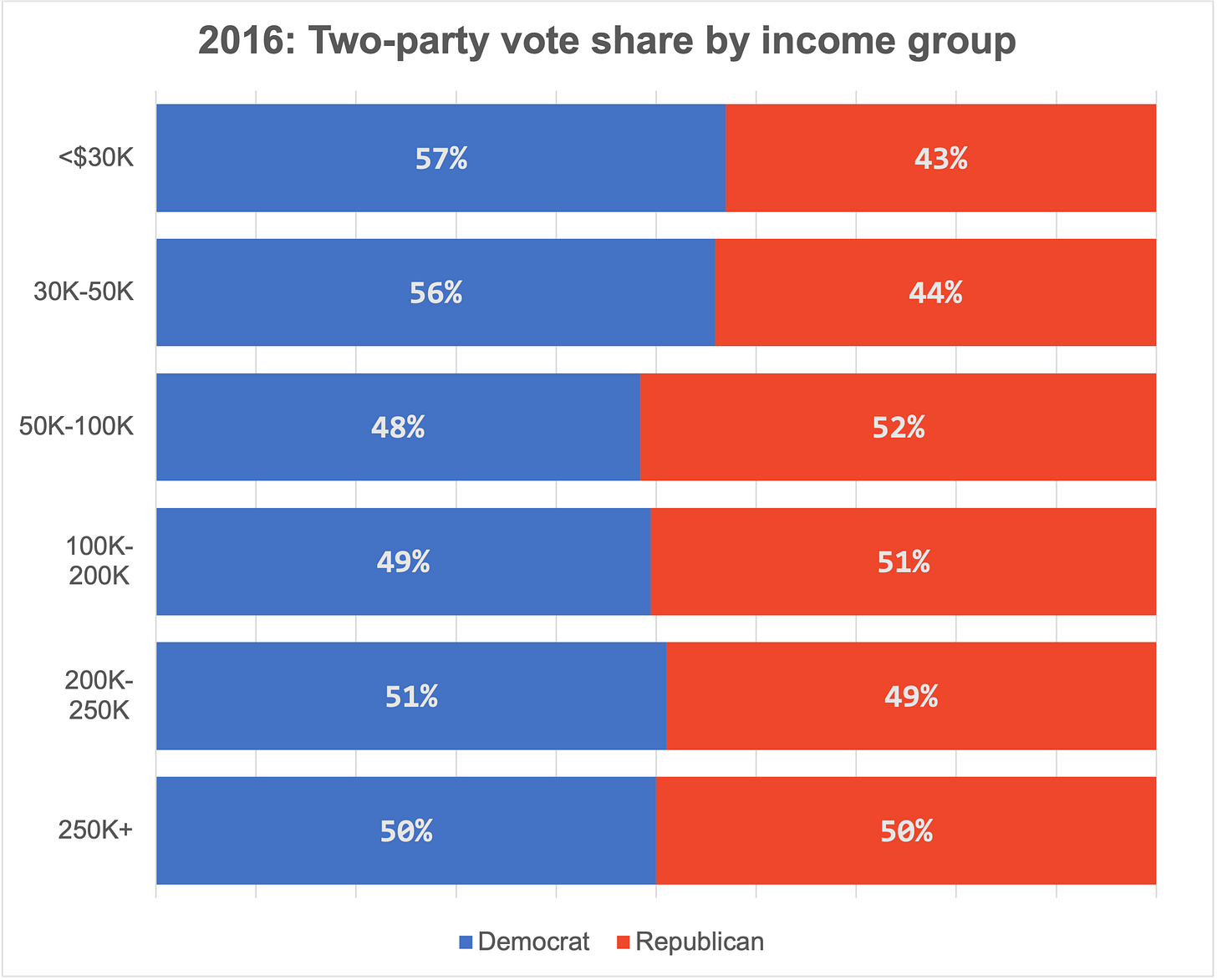

In 2016, however, Donald Trump did as well among poorer voters as any Republican since Reagan. And here, we can’t not invoke race while doing the results justice. Trump’s gains were predominately with the Northern and Midwestern white working class; he didn’t do any better than McCain among the poor Black voters of the Mississippi Delta or the working-class Hispanics of the Southwest. Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, won about half of the wealthiest voters as Trump underperformed Romney among the wealthy.5

In 2020, something unprecedented happened in recent American politics: Democrats won the wealthiest voters, or at least the wealthiest subgroup that the exit polls6 tracked that year (people making $100K or more). Among poorer voters, the story is more complicated. Biden did just a hair better with the white working-class than Clinton — not a lot better, but enough to get him over the finish line in the Upper Midwest — but considerably worse than her with Hispanics and slightly worse among Black voters.

This class depolarization is beginning to drive some degree of racial depolarization. Since 2000 (with a partial interruption under Obama) Democrats have generally gained ground with wealthy voters and lost ground with poorer ones. If you extrapolate the trend forward, it’s necessarily the case that Democrats will see their standing erode with Black and Hispanic Americans because that’s where the remaining working-class votes are — working-class white voters have already shifted en masse to Trump.

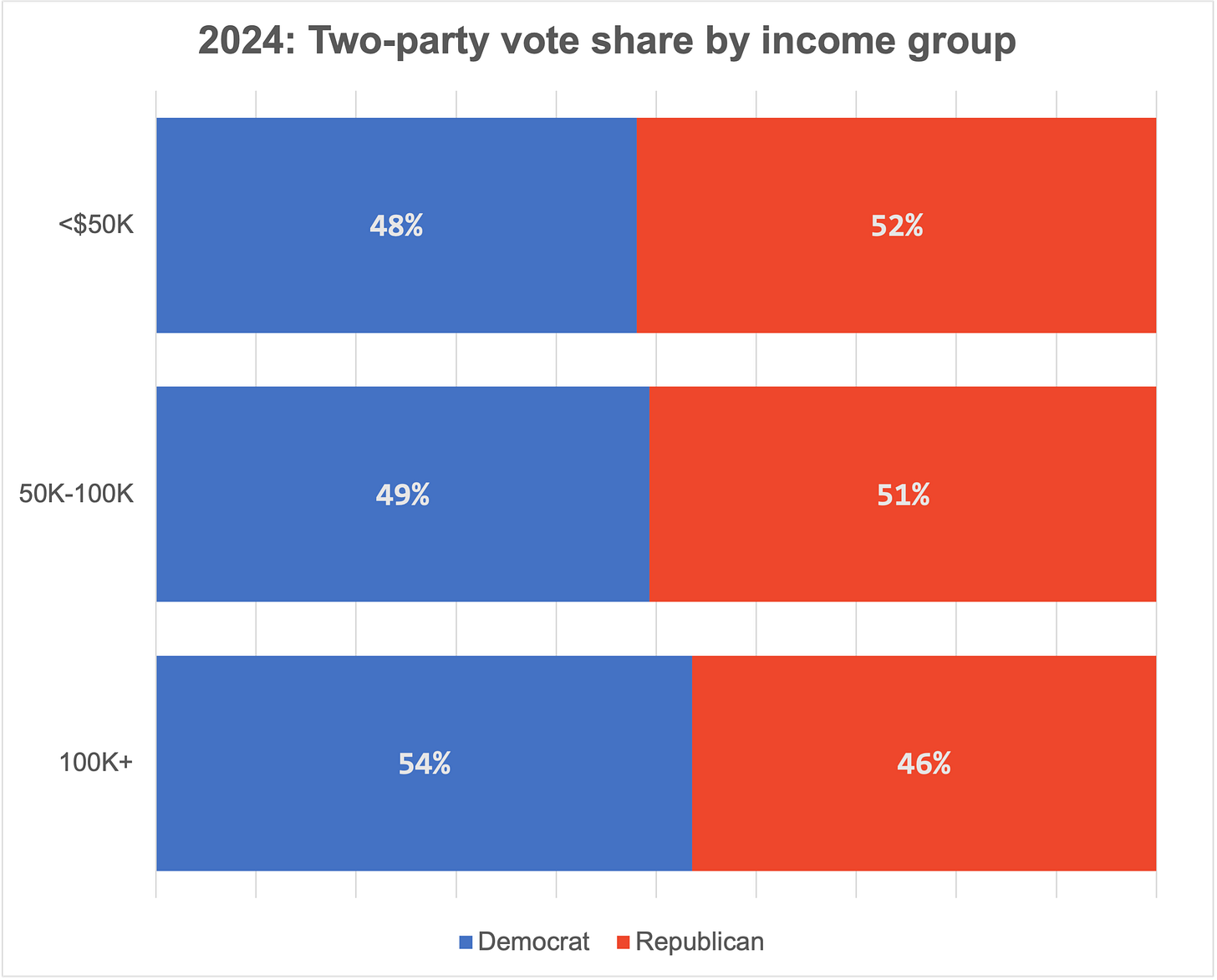

And in 2024, it’s possible that the longstanding economic class division in American politics will fully invert and that Republicans will do slightly better with poor voters than with wealthy ones. Here is data taken from Adam Carlson’s outstanding poll crosstab aggregator, for instance.7 Every polling firm uses its own income classifications, but the most common brackets are below $50K, between $50K and $100K, and above $100K in annual income. These are the numbers for those groups, averaging every poll I could find in Carlson’s spreadsheet from December through March.

Again, this is preliminary — it’s only March. But the polls show that Biden’s decline relative to 2020 is entirely among voters making $50K or less. He’s doing just as well as in 2020 with the $100K+ group and roughly as well among the middle class.

Could that be a hangover from inflation? Perhaps. Inflation is generally thought to hit the poor harder, in part because the wealthy are more likely to have net worth in real estate (which can be an inflation pass-through if housing prices are rising with everything else) or the stock market (also something of an inflation hedge, although that story is more complicated). Whether the most recent bout of inflation during Biden’s term disproportionately affected the poor is less clear, however.8

Economics no longer functions as culture wars

But all of that assumes that economic voting is a thing when it may have become less of one. Certainly, class politics have become trickier to navigate for Democrats. They represent the cultural and intellectual elite, which isn’t entirely new; Hollywood and academia have long been left-coded. But they are also increasingly the party of the economic elite, if only because the coattails of educational polarization drag some high-income earners into the Democratic coalition.

Sometimes this makes for strange bedfellows. Obama’s rise was correlated with the rise of Silicon Valley and the often very wealthy tech elite. That relationship is becoming rocky; Silicon Valley elites — by which I mean VCs and founders, not rank-and-file tech workers — are sour with Democrats over what I call Social Justice Leftism but everyone else calls wokeness. I spoke with enough Silicon Valley types for my forthcoming book to believe those concerns are sincere — however, cultural issues can also be a convenient scapegoat because it’s in the economic interests of these Silicon Valley leaders to vote Republican for lower taxes and fewer regulations on business.

You can tell something of the same story for finance. The finance guys I know are liberal-ish on social issues, but it doesn’t take that much to push them into complaints about high taxes, how the private schools they’re sending their kids to have become too left-wing, and so on. Now, finance and tech may not cost Democrats all that many votes, or at least not outside of California, Connecticut and New York. But they exert pressure on the party through their financial and cultural influence.

Meanwhile, some of the policies that Democrats advocate for benefit the managerial and professional class more than the working poor. Student loan debt cancellation by definition helped Democrats’ college-educated coalition, but it was actually somewhat economically regressive. The SALT tax deduction that suburban Democrats in high-tax states advocate for is highly regressive, meanwhile. COVID lockdowns are a more subtle example; work-from-home benefitted the laptop class more than essential workers or small-business owners.

Don’t get me wrong; if I were a poor person voting solely out of economic interest, I’d vote for Biden and be thankful for the strong labor market recovery. And I’d be carefully tracking Republican efforts to cut Medicare and Social Security.

But some of the other things I’d want, like a public option for health care, have been low priorities for the administration. And some things about Biden’s messaging would turn me off, like the emphasis on Trump, Trump, Trump. In Biden’s re-election kickoff speech in January, he mentioned “democracy” 31 times and Social Security zero times. Personally, I’m somewhat persuaded by the “democracy is on the ballot” stuff or at least some diluted version of it. But I’m not the sort of voter Biden needs to win over. It’s messaging targeted at the educated classes, not the working class.

Class depolarization also makes it harder for either party to tout its economic accomplishments. Take a look at (or read the transcript of) Reagan’s 1984 convention speech:

Reagan is very focused on a single message here, which I’ll paraphrase as follows: Democrats may say they’re the party of the working class, but look at the scoreboard — it’s actually Republican policies that are lifting the economy up.

That’s a powerful message, because it ran parallel to what was then a prominent political fault line between the rich (Republican) and the poor (Democrats). Reagan was saying: I’m the guy for people like you. It cleverly exploited class politics. And it worked: Reagan won 26 percent (!) of Democrats in 1984. Meanwhile, when the economy performed well during a Democratic presidency, a Democratic nominee could say the same thing: I’m the guy for people like you, and the condition of the economy proves it. It was economics as culture wars, not just for its own sake.

With class lines muddled, it’s harder to make that argument. Republicans are the party of rich guys in manufacturing, fossil fuels and real estate, but Democrats are the party of rich guys on Wall Street, and in Silicon Valley and Hollywood. Republicans are the party of the white working class, but Democrats are the party of the Black and Hispanic working class. The parties can bend their pitch to the contours of this more complicated fault zone. But “it’s the economy, stupid” is no longer as much of a straight line through it.

Or occasionally the second Friday.

More about that soon! I have a couple of things to nail down so don’t take any of this as final. But it’s likely that there will be some public version of the presidential model. It will probably be more of the “slow food” version discussed here, with a lot of context around the numbers. And the probabilities may be behind the paywall. I’m not sure I can take constant jittery updates with every new poll in another election involving Trump, and I’m not sure how much journalistic value that provides anyway.

I say “semi-reliable” because exit polls have a lot of problems and are often incorrectly treated as ground truth. But we’ll leave that aside for now.

Note that this comparison isn’t completely apples-to-apples because the exit polls are constantly switching how many income groups they track and where the lines are drawn.

I’m not sure why the exit polls broke out so many subgroups among wealthy voters that year — no one needed to know how people earning between exactly $200K and $250K voted, for instance. But 2016 was a strange time; the Chicago Cubs won the World Series.

For 2020, I’m using the AP exit poll for Fox News and other organizations because it breaks out more income groups, but the Edison Research exit poll (the main provider of exit polling prior to 2020) tells pretty much the same story.

Which is almost useful enough to make me not hate on crosstab-lovers.

There was actually some net decline in income inequality in the first two years of Biden’s term because of a robust labor market combined with a poor year for the stock market in 2022.

Anyone in the bottom third of the economy is probably disproportionately concerned with the cost of food and housing because a far greater share of their income is devoted to those categories compared to wealthier cohorts. And the last I checked food and housing were outpacing the general index for inflation.

I think it makes a lot more sense to divide the electorate into segments rather than treat it as a monolith. And it simply makes deep intuitive sense to me that the working poor and middle class will be far more concerned with inflation simply because they are far more impacted by inflation.

Plus it is most likely that these variables/factors aren't completely independent. Josh Kraushaar posted on Twitter something like "Inflation has been rocket fuel for the ongoing shift of Hispanic voters to the GOP".