A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a short post about how you should steel yourself for 2024 because it’s going to be very long election year. But I kind of chickened out: originally, that post was more about my own election-related stress. For the first time since 2008, I’m not under contract with any media entity for election coverage. I have a choice about how to cover the election, or even whether to cover it at all. I still have some decisions to make — decisions that I’ve been procrastinating on for a while now.

OK, OK, let’s stop with this “cover the election at all” business. I’ve admitted to myself that I’m probably going to be covering 2024 in some capacity. As much as I might want to be on a beach in Thailand or a vineyard in Bordeaux throughout the duration of the campaign, I know that realistically I’ll be thinking about the election whether I want to or not. That being the case, I’ll probably want to write about it. (Revealed preference: I’ve already been writing about the election more here than I was planning. I promise there’s a bunch of NBA stuff coming soon.)

Beyond that, I still don’t know very much. We’ve built a nice little community at Silver Bulletin, and I figure that sharing my thought process couldn’t hurt.

Some of the anxiety is inspired by the way the primary process is unfolding. Covering — I don’t know — a Raphael Warnock vs. Nikki Haley election sounds almost refreshing. However, barring some big surprises, that’s not what we’ll be getting. A Trump-Biden rematch is not quite inevitable, but it’s looking rather likely. It may be that neither primary is really competitive at all. That means there could be another 14 months of a potentially very close election where everybody is on hair-trigger but there also aren’t a lot of new storylines about the campaign from day to day.

Frankly, I can already sense that this is going to lead to a lot of annoying arguments, such as about the reliability of polling and about the role played by election forecasting and horse-race coverage. These discussions, like everything else in an election year, will be filtered through a highly partisan lens. (Any election involving Trump tends to make these issues worse.) It already feels like September 2024, even though it’s September 2023, so I can only imagine what it will feel like a year from now.

I also want to cover the election without being a participant in the story. I don’t want to be an avatar for someone else’s grievances about election coverage. I don’t want to be name-dropped in Nancy Pelosi’s fundraising emails. I don’t want some media blogger to write something like: “You know who really has a lot on the line tonight? Nate Silver.” Not when the actual stakes of the election are so high.

Although written content is easy enough to scale up or down, the more difficult question is what to do with the election model. (I still retain that intellectual property even after my split with Disney.) I don’t want to make this some philosophical rumination on the journalistic value of probabilistic election forecasts. I do think most of the critiques are ill-considered — forecasting is one of the fundamental ways to test whether your view of the world is accurate, and journalists ought to be concerned with accuracy — but let’s leave it at that.

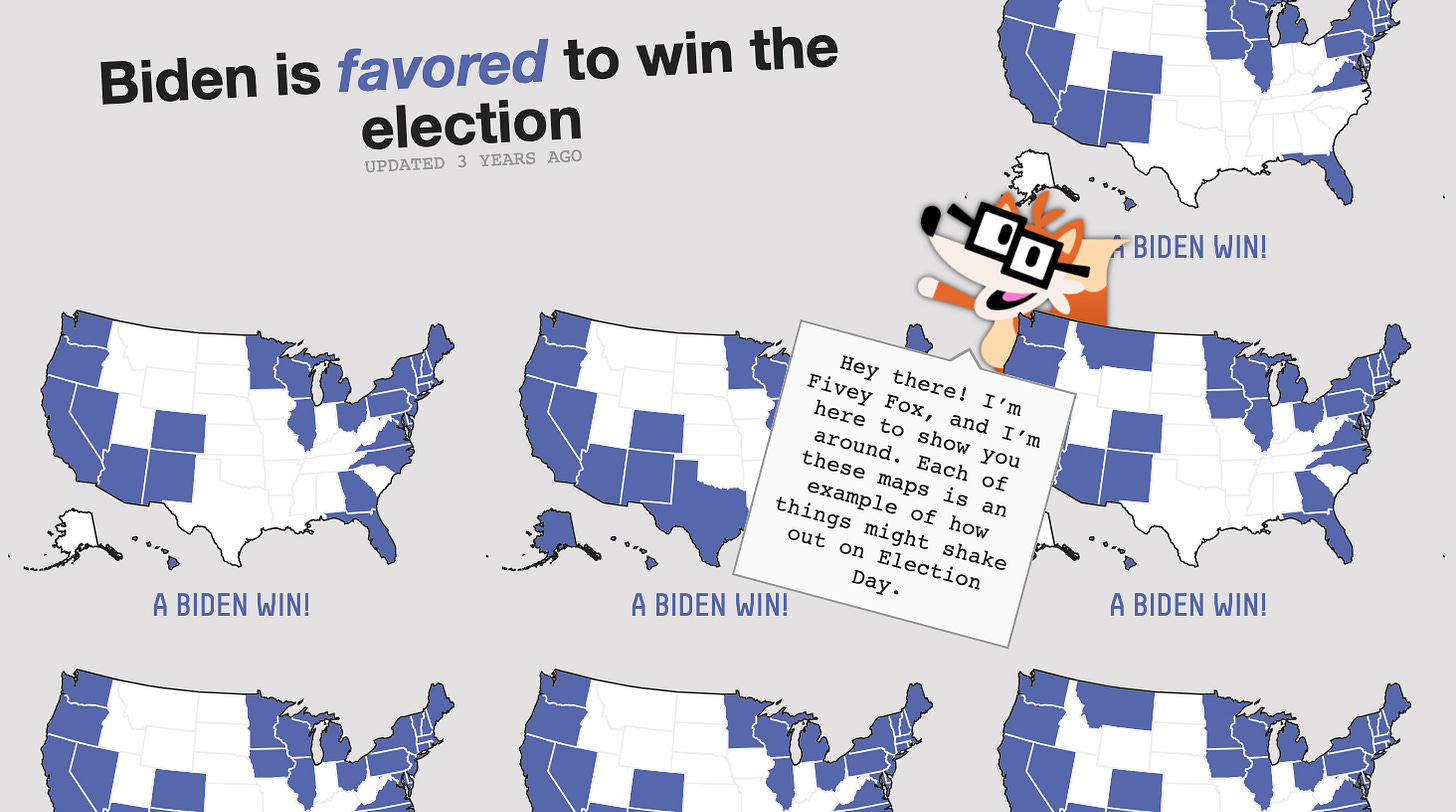

However, the FiveThirtyEight election model was subject to a certain, weird problem: it was way too popular. No seriously. It was too popular, and it tended to swallow everything else in its wake. The election forecasts we ran at FiveThirtyEight were seen by very large numbers of people — tens of millions of people. In fact, the 2016 forecast was literally the most engaging piece of content on the English-speaking Internet, according to Chartbeat.

When a product reaches that scale, you lose control of the narrative about it. As much as I might have been literally screaming at people to take Trump’s chances seriously in 2016, for instance, far more people saw the numbers than read my careful contextualizations about them.

I don’t think the story is quite so simple as “people don’t understand probability” or “people round 70 percent up to 100” (there’s actually not much empirical evidence for the latter claim1). It’s more just that people interpret these forecasts in a lot of different ways, and those interpretations are mediated by a lot of partisanship and election-related stress. For every one reader who was interested in forecasting as an intellectual exercise — or who at least appreciated the effort to make horse-race coverage more rigorous — there were probably 10 who just wanted reassurance that their guy was going to win.

Impressions of the model can also be affected by media coverage readers see elsewhere, or by things they hear about the forecast from other people. Or, people may misattribute results they see from a different model to mine.2 In years like 2016 and 2022, for instance, the FiveThirtyEight model often got lumped in with other coverage even though it actually bucked it. (Our model was much more bullish on Trump than the consensus in 2016 and somewhat more bullish on Democrats than the consensus in 2022.) Indeed, there’s a whole narrative about the FiveThirtyEight election models among political partisans that’s completely detached from their long, well-documented track record of strong calibration and accuracy. It’s hard to escape the depressing conclusion that many news consumers aren’t that interested in accuracy at all.

I have a book coming out next year about gambling and risk that I’m super excited about — it doesn’t really have anything to do with elections at all, and is only tangentially about politics. I’ve found it extremely refreshing to cover a new beat. I want to cover the election in the context of those other things I’m doing. So the question is whether I can find a way to orient the model in the right way to the right audience — without it completely taking over my life. Otherwise, it might not be a good risk to take. Alternatives might involve taking the model private, selling it, or even just taking the year off from modeling and approaching the election with a little more arm’s-length detachment. Some possibilities I’ve considered:

Frankly, putting the numbers behind a paywall might help a lot to draw a more self-selected audience.

I’ve also had interesting conversations with outside parties about aiming for a different type of customer. At FiveThirtyEight, for better or worse, we were catering to the politics junkie audience. Leaning more into the business/tech/econ crowd or even the forecasting/gambling crowd might be a better fit for the model.

I’ve had other conversations about doing a deliberately low-fi version of the forecast. Maybe I’d hire a couple of people, and instead of updating the numbers 24/7, we’d publish them once or twice a week. Maybe we’d round probabilities to the nearest 5 percent. Maybe we’d have some simple, attractive graphics, but nothing too immersive. Maybe we could cultivate a healthier relationship between readers and the forecast rather than having people click the refresh button 10 times a day.

Finally — and I have to admit this is an option I’m finding increasingly attractive — I’ve also had some discussions about taking the model private, whether selling it outright or licensing it for the cycle. People use election forecasts to hedge financial risk and to make other sorts of bets. One could even argue that this is the better use case for the model. Whether Trump’s chances are 30 percent or 50 percent or 70 percent might not affect your decision-making that much as a voter. But it’s definitely relevant if you have to make some calculated financial decisions based on the outcome.

If you’re interested in discussing any of these possibilities, you can email me at NATE DOT SILVER DOT MEDIA AT GMAIL DOT COM. Thanks for reading, and back to our regularly-scheduled content soon.

The seeds of a future Silver Bulletin post!

I still have people tweeting screenshots of the Upshot’s 2016 banner headline at me, for instance.

If you do anything please bring back the electoral college snake! That was data visualization at its finest!

I like the idea of combining options 3 and 4. License the full model to companies they need that level of precision, and also publish a simplified, less precise version of the model that’s refreshed weekly.

I think I started listening to the FiveThirtyEight podcast a little after the 2016 election, and started reading written content regularly in 2019 or so. I believe I got more value from the written/podcast content than the model alone because the contextualization helped me better understand the trends and larger political environment.