Zohran’s high-risk, high-reward strategy

What will it take for the new mayor to maintain a winning coalition?

Note: the Comedy Cellar event previously listed here with Clare Malone and Galen Druke has sold out! I’ll see some of you on Jan. 27.

Today’s newsletter was inspired by a reader’s question about Zohran Mamdani, who was inaugurated as mayor on Jan. 1. But for record-keeping purposes, it’s not an “official” SBSQ; see last week for responses on Tim Walz and Venezuela. I’ve also got answers on some more “fun” questions written up, but let’s save those for a slower news cycle.

Speaking of which, I’ve been struggling with whether to write anything about the killing of Renee Good by an ICE agent in Minneapolis last week. I generally find this type of story difficult to cover. A lack of comment should not be taken to indicate a lack of concern, however. There’s a lot that might be said about how the story has been framed in the media or why partisans can agree on so little. But I think that’s losing sight of the bigger picture. The bottom line is that while there were a lot of “bad choices” made, this woman shouldn’t have wound up dead.1

OK onto our question from reader Jack:

Question for SBSQ: In your River vs. Village framework, how would you classify Zohran Mamdani? On the one hand, his outsider positioning and seemingly high-risk, high-reward strategy feel very “River” in terms of narrative and movement dynamics. On the other hand, his core base is the very definition of the “Village” - highly online members of the media classes.

Jack is referring to the dichotomy in my book between the Village — basically, the risk-averse liberal establishment embodied by institutions like the mainstream media, the Democratic Party, and elite higher education — and the more individualistic and risk-tolerant River, associated with Las Vegas, Wall Street, and Silicon Valley. And I think he’s capturing something unique, and maybe a little contradictory, about Mamdani. On the one hand, Mamdani indeed wears the socialist label proudly. “I was elected as a democratic socialist and I will govern as a democratic socialist,” Mamdani said in his inaugural address. He was sworn in by Bernie Sanders, and even promised to “replace the frigidity of rugged individualism with the warmth of collectivism”.

But Zohran also fits into a classic sort of NYC striver archetype that could be from a Safdie brothers film. He went to Bronx Science (a highly selective public school) and ran for student vice president. He tried out a couple of other careers before entering politics. He famously dresses well and is married to an artist who did a fashion shoot for The Cut. And he ran in a mayoral election that almost nobody thought he had a chance to win, and wound up becoming the second-youngest mayor ever of the nation’s largest city. He even apparently played poker while serving in the state legislature in Albany. This is not a nitty politician who waited to pay his dues.

And I think this is important to understanding his appeal among a certain type of voter who isn’t necessarily a Village type. For a younger college-educated professional, even in industries like finance, there’s a certain comfort level there. They might find Zohran likable and recognizable, even if they don’t necessarily agree with his policy platform. He might be an outsider, but not one who seems threatening.

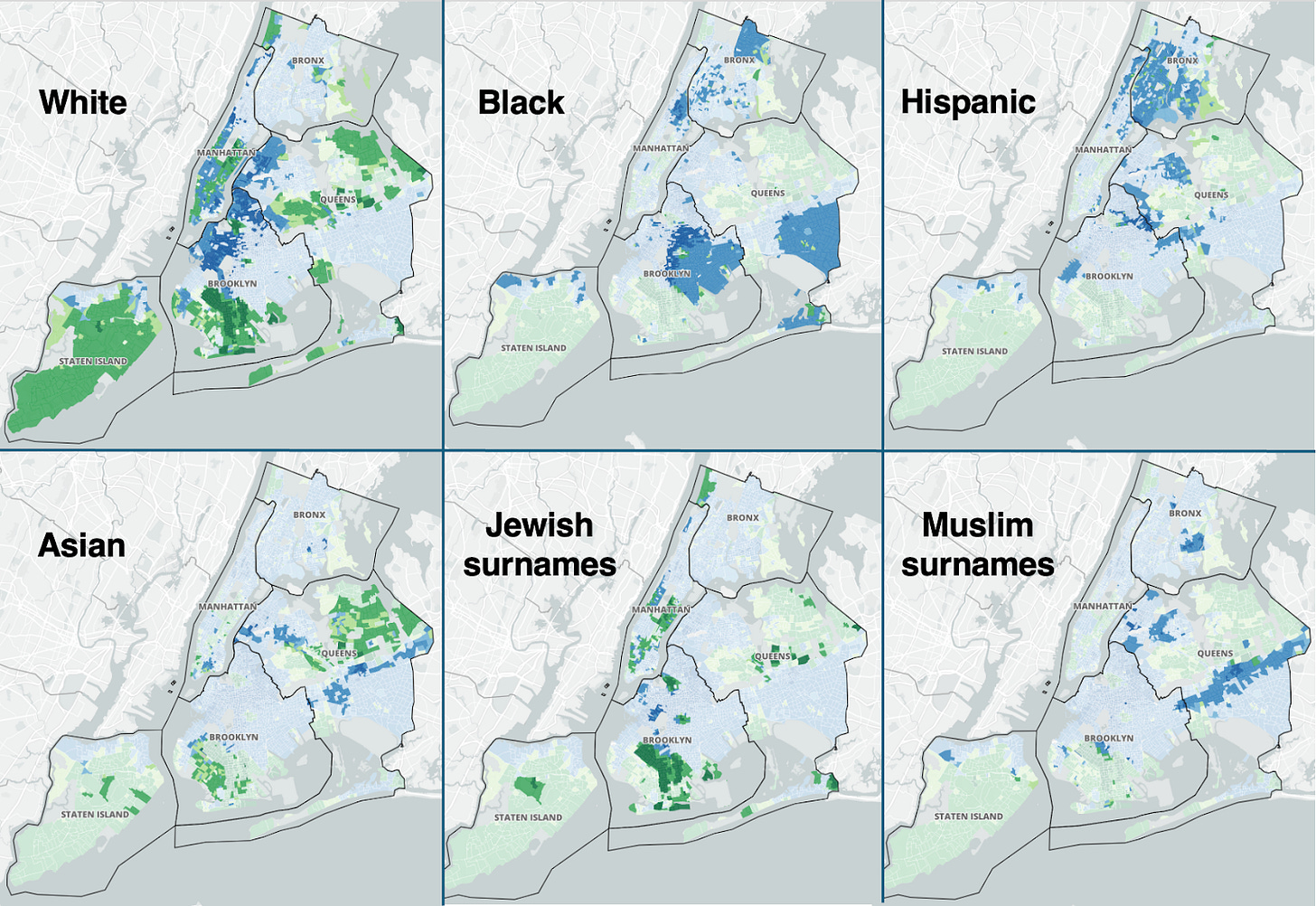

Let’s take a look at a series of maps that I’ve adopted from CUNY’s outstanding NYC Election Atlas. While dividing the electorate around racial, ethnic, or religious lines can be overly reductive, it tells a pretty clear story in New York. Here’s how the vote looked based on the dominant ethnic group in each precinct. On these maps, Zohran is blue, and Andrew Cuomo is green.

Start with the two boxes on the bottom right. Muslim communities went overwhelmingly for Mamdani. However, Cuomo won Jewish voters roughly 2:1. In New York in particular, many Jewish voters are fairly secular — still, Cuomo won everything from Hasidic Jewish communities to the more Jew-ish (hyphen intentional) and secular Upper East Side.

Mamdani performed extremely well in Black precincts, which had once been a Cuomo strength, improving on a weaker performance in the primaries. And while you can detect a few specs of green on the Hispanic precinct map, that was another major part of his coalition. In Asian communities, however, he struggled. To be fair, “Asian” is a sometimes unhelpful label that contains multitudes: Mamdani performed especially poorly among Chinese and other East Asian communities but better in South Asian ones, perhaps reflecting his Indian heritage.

White voters are, in their own way, a minority group in NYC (non-Hispanic whites make up about a third of the population). And those voters were highly divided in the mayoral race by neighborhood and borough. On Staten Island and in the whiter, outer reaches of Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx, where the dominant ethnic groups are Italian, Irish and Russian, Cuomo romped to huge margins. Zohran crushed Cuomo in what Michael Lange has dubbed the “commie corridor”, however. These are younger, ethnically mixed but increasingly gentrified (and white) neighborhoods like Greenpoint, Williamsburg, Bushwick, also stretching across the East River into the East Village and the Lower East Side in Manhattan. A decade or two ago, we might have described these neighborhoods as “hipster”, though housing prices are such that they don’t really consist of starving artists. However, these are places where people working in the media and other creative professions tend to live.

But Manhattan was actually the swing borough. Mamdani performed well in the commie corridor spillover on the East Side, as I mentioned, as well as in the predominantly Black and Hispanic “Green Cab Zone” north of Central Park, and gay-friendly Hell’s Kitchen. Cuomo had some real pockets of strength in UES. Outside of that, the results in Manhattan closely replicated the roughly 50-40 split to Mamdani citywide, including neighborhoods like Chelsea, Soho and the West Village that are more yuppie than hipster.

In general, among white voters, Mamdani’s support followed an inverted “U” pattern: he did poorly among the poorest whites, and mediocrely among the very wealthiest, but was strong among what by New York City standards is the upper-middle class. Still, Mamdani basically split the vote with Cuomo even in the Financial District. He held his own in Soho and Tribeca, the city’s most expensive neighborhoods. He was comparatively much stronger with wealthier voters than, say, Sanders in his 2016 primary against Hillary Clinton.

It might nevertheless seem like a pretty tenuous coalition. Mamdani just barely scraped by with an overall majority (50.8 percent). However, this is actually pretty typical in the city. Majorities or pluralities involving intricate combinations of ethnic and socioeconomic groups that might otherwise seem to have little in common are the norm rather than the exception in cities as diverse as New York. Furthermore, mayors from La Guardia to Giuliani to Bloomberg to Ed Koch all won with less than Zohran’s 50.8 percent in their initial races before going on to win re-election, sometimes multiple times.

Then again, we’re living in more polarized times than we once did. By the end of his race against Cuomo, about 45 percent of voters had an unfavorable view of Mamdani, and most of those unfavorables were “strongly unfavorable.” One poll since the election has shown Mamdani’s favorability numbers improving, but that may be a short-lived “honeymoon effect” that will wear off quickly.

So there might be something of a ceiling on his support. Although Mamdani tipped his hat to Trump supporters in his inaugural address, only about 4 percent of them voted for him. He’s unlikely to ever make much headway with “fiscally conservative but socially moderate” Wall Street types. We’ll see about Jewish voters, who are 10 to 15 percent of the population in New York. But Julie Menin, who just became the city’s first Jewish city council speaker, has already registered misgivings about Mamdani having revoked Eric Adams executive orders on Israel and antisemitism.

In his speech, meanwhile, Mamdani signaled a desire to be a transformational mayor:

In writing this address, I have been told that this is the occasion to reset expectations, that I should use this opportunity to encourage the people of New York to ask for little and expect even less. I will do no such thing. The only expectation I seek to reset is that of small expectations.

Beginning today, we will govern expansively and audaciously. We may not always succeed. But never will we be accused of lacking the courage to try.

To those who insist that the era of big government is over, hear me when I say this: No longer will City Hall hesitate to use its power to improve New Yorkers’ lives.

This won’t be so easy. New York City has its veto points, from the city council to the state legislature (which must approve tax increases in the city) to the more informal centers of power like the police force and the media. This is certainly not a risk-averse approach. But will it work?