SBSQ #17: How should you prepare for an AI future?

Plus, why has Georgia stayed relatively blue? And who holds the cards in Trump vs. Elon?

Welcome to edition #17 of Silver Bulletin Subscriber Questions. We’ll stick to a more classic SBSQ format this time — four medium-length responses on a grab bag of topics: one question about AI, one about sports, and two about politics. I’d encourage you to leave questions for edition #18 in the comments below.

Before we get into those, there were several queries about the timing of particular features — and especially Part III of the Kamala Harris campaign autopsy. I’m glad there’s still interest in that piece — and it’s coming. I’ll also confess to not exactly having prioritized it; I’ve written a lot about the shortcomings of Harris, Joe Biden, and Democrats in general lately. I suppose I’m hoping we might get a slightly fresher perspective a few weeks into the new Trump administration, partly because it makes the consequences of those shortcomings more clear. But there are also some competing short-term priorities. We want to get our revised pollster ratings up soon, accompanied by our final word on how the polls performed in 2024. And we want to start publishing Trump approval ratings soon, too. Once those are ready, I’ll turn back to the Harris autopsy — which most likely means mid-to-late February.

In this edition:

What steps should you take now to prepare for an AI Industrial Revolution?

Why did Georgia (somewhat) resist the Red Wave?

How long will the Elon-Trump relationship survive?

Are major league sports franchises irrationally focused on the short run?

What steps should you take now to prepare for an AI Industrial Revolution?

Zach Reuss asks:

In your article "It's time to come to grips with AI" you wrote:

"I don’t think there’s any inherent trade-off between considering medium-sized risks, existential ones, and everything in between (particularly mass job displacement)"

I'd love to hear you (and maybe Maria) give some advice on how people can hedge these risks, particularly around that parenthetical on job displacement.

I'm someone who's still relatively early in their career and who's future earning potential is over indexed on the presumption that being better than most at analytical thinking is a differentiated skill that will demand a significant wage premium.

I would guess a fair portion of your readers are knowledge economy types who also fall into this bucket.

There are actions I'm considering, like buying into some AI specific ETFs, but if AI is really the next industrial revolution, what steps should people aware of that possibility be taking now?

Let me start by stipulating that I don’t see Silicon Valley’s prediction of a rapid AI takeoff within 2-5 years as the base case. Instead, I see it as being possible. It’s reasonable to discount Silicon Valley’s optimism somewhat — or even quite a bit. Overall, my base case is closer to Tyler Cowen’s in his recent interview with Dwarkesh Patel. For the next decade, if not longer, there are likely to be a lot of human bottlenecks, even if there aren’t technological or resource bottlenecks (and there might be). The point of Monday’s story, though, is that you can deflate the hype bubble by half or two-thirds, and AI is still likely to play a major role in the future of the economy, as well as geopolitics.

So your age here matters a lot, Zach. I turned 47 this month. For various reasons — but mostly having a lot of things I could pivot to at medium time frames — I don’t worry too much about AI displacing me.1 It sounds like you’re in your twenties or early thirties, though, which is a different story.

Most of my advice is pretty obvious:

First, you should just get in the habit of using LLMs and other AI tools. There’s likely to be some immediate productivity benefit, and you’ll develop your intuitions for the better and worse use cases.

The second tip is also simple: your media consumption diet should include plenty of tech, AI, and finance news — sort of the stuff in the Cowen / Matt Levine sweet spot. These are both higher-leverage topics and more interesting than the political controversy du jour.

Third, you’ll want to invest in equities that will benefit from growth in the more dynamic parts of the world, mostly meaning the US and China. Maybe you should overindex on tech- and AI-adjacent stocks, but a relatively balanced portfolio is fine too as there are also cases where the returns from AI-fueled growth could show up elsewhere in corporate profits. It’s almost always been good advice for younger investors to focus on long-run growth anyway.

Fourth, you should increase your estimate of the opportunity costs from not spending the next several years productively. Taking the next two years off to teach English in Cambodia as you “find yourself” or half-assing your way through a degree program you’re not sure you need — these are choices, and they might be the right choices for you, but they could be relatively costly. It’s at least possible that the AI optimists are right and we are at some sort of inflection point, in which case there could be first-mover advantages and even some lock-in — whoever is ahead in the race in, say, 2027 might only continue to pull further ahead. Even if not, we’re probably out of the Great Stagnation. Say what you want about Trump’s first two weeks in office, but the world at least feels more dynamic than it has in some time between technological growth and geopolitical risks. You also probably don’t want to find yourself in some apprenticeship-type situation — a lot of government and academic jobs would fall into this category — where you earn your credentials and then slowly work your way up a ladder with no rewards on the top rungs.

Fifth, I think you should treat AI’s impacts as being more unpredictable than not. Which means there’s not going to be any foolproof plan. (This also echoes Cowen’s advice.) Yes, there are some exceptions. Victor Wembanyama’s NBA career will not be threatened by AI, whereas someone relying on income from being an Uber driver might have to learn

to codesome new skills. (Based on a sample size of one ride this summer, Waymo is already better than the median Uber experience.) But questions seemingly as simple as what effect faster AI compute times will have on the demand for semiconductor chips are not straightforward. And that’s even more true for exactly what skills will be in demand. We’re basically all playing a game of bumper billiards governed by exponential growth in some areas, but with human and technological bottlenecks acting as bumpers. Where everyone ends up is hard to say.

If AI’s impacts are unpredictable, what does that mean for your professional development? Maybe we can extrapolate from the production function that Cowen outlined to Patel. Bundles of skills — you do X very well, have complementary skills Y and Z, and then work really hard — are likely to remain scarce. To formalize this, you might think of the demand for knowledge-economy work — basically, the market value of your services — as being dictated by the following function:

G * S * P

Where “G” is general applied, problem-solving intelligence — not the same as raw IQ — “S” is specialized domain knowledge, and “P” is personal and interpersonal skills. They have a multiplicative effect because any of these are potentially limiting factors. If you have no work ethic and are hard to work with, you aren’t going to get very far, no matter how smart you are.

AI may increase the importance of the “P” relative to the “G” and “S.” AI services, after all, may be missing the “human touch.” (If nothing else, highly curated services that appeal to rich people will likely remain a good gig, especially if AI creates more rich people.) Still, I don’t expect this basic equation to change, even if “G” and “S” increasingly involve being an “AI whisperer” or understanding AI’s shortcomings.

But in an AI-driven world, there are probably larger exponentials on these factors. Being a 9.7 out of 10 in some category will potentially be much more remunerative than being a 9.3, or certainly an 8.1 — especially if AI can perform at an 8.7.

All of this is not super actionable, I realize — and sort of pessimistic. Unfortunately, we’re probably moving to more and more of a winner-take-all world, and AI is only likely to accelerate that. “Try to be really good at several things, ideally from a mix of the G, S, and P buckets, and then world-class at another thing, and then hope the slot machine reels land in a spot such that the combination of skills you possess happens to be valued in the new economy and you hit the jackpot” — OK, great.

But I do think, from the “P” bucket, you want to cultivate the two R’s — resilience and resourcefulness. Resilience means being able and willing to pivot quickly — quitting a job a year too soon rather than a year too late — coping with stress and setbacks and not being bogged down by neurotic people or institutions. And resourcefulness means being a self-starter, cultivating your skills and your network, and not waiting around for anyone to give you permission. And having an entrepreneurial mindset. I hate to say it, but some willingness to engage in self-promotion doesn’t hurt either. AI may replicate many human skills, but brands will probably still be valuable, especially in a world with more focal points.

Why did Georgia (somewhat) resist the Red Wave?

Jabster asks:

It's political, but I will throw it in for SBSQ #17.

Why did Georgia (especially the Atlanta metro; also maybe Arizona and Utah) move so hard to the Left in the 2024 presidential election? What about downballot?

It seems like the Georgia (again, might just be metro Atlanta wagging the dog as it often does) moved opposite to most of the rest of the country. Why/how did that happen?

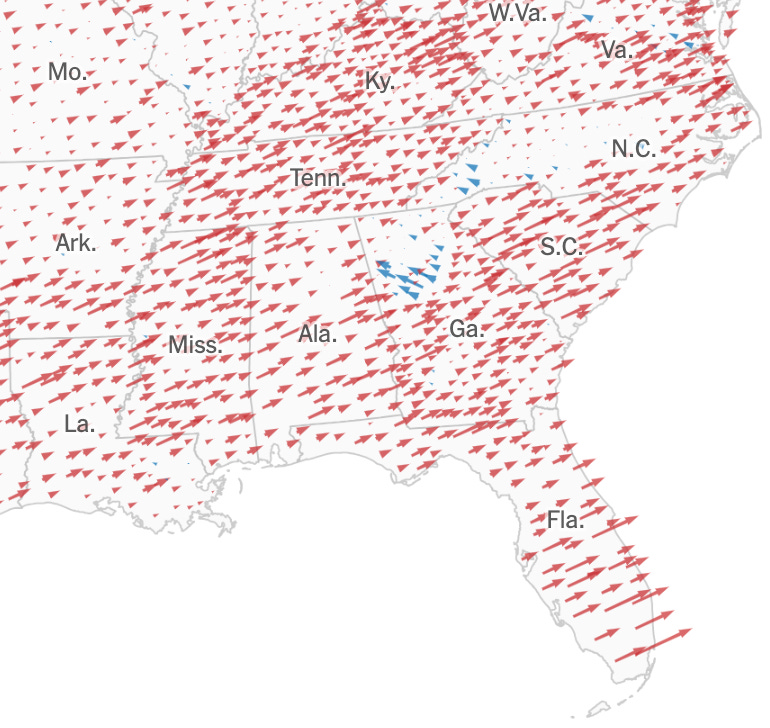

Relative to 2020, Georgia was Kamala Harris’s least bad swing state. She lost it by just 2.2 percentage points, compared to Joe Biden’s 0.3-point win in 2020. There were also virtually no Republican gains in the popular vote for the US House in Georgia, and no seats changed hands. Indeed, Georgia (and Western North Carolina, which may have been affected by Hurricane Helene) stands out on the map: the Atlanta suburbs are among the few places anywhere where Harris improved Biden’s performance.

All of this counts as good news for Democrats. Georgia is a high-leverage state. It contributes to a diminishing Electoral College/popular vote gap, and Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock’s Senate seats may be easier than you’d think to defend in 2026 and 2028.

But why is Georgia trending this way — or at least resisting the red trend — when other states aren’t?