Nebraska probably won't cost Biden the Electoral College

Everything you always wanted to know about that one electoral vote in Omaha but were afraid to ask.

We’re covering a lot of ground at Silver Bulletin lately, from the NCAA tournament to the politics of AI algorithms. But obscure topics involving the Electoral College? That’s still a Nate bat signal — so you’re getting a newsletter about it.

Nebraska isn’t a swing state. It can’t possibly matter to the Electoral College. So why are you emailing me about it?

While those of you who read Silver Bulletin for our electoral politics coverage will probably know this, others of you might not: Nebraska and Maine award one electoral vote each to the winner of each congressional district, along with two votes to the statewide winner.

And this is news now because Nebraska Republicans, under pressure from Donald Trump and conservative groups, are considering passing a bill that would revert the state to a winner-take-all system. Although it’s not all that likely, it’s plausible this could determine who wins the next election.

In 2008, Barack Obama won Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District, which is basically coterminous with the Omaha metro area. And Joe Biden won the 2nd District in 2020. This is a reflection of the fact that urban areas, even in the country’s heartland, tend to be blue these days.

However, Maine uses the same system, and Trump won Maine’s 2nd Congressional District in 2016 and 2020. The Maine 2nd marches to its own drummer: a place where you might see a gay pride flag on one side of the highway and a MAGA flag on the other (and maybe even a French-language sign if you go far enough east or north). But although the district — which I visit almost every summer — is known by tourists like me for Acadia National Park, lobster rolls, and chintzy antique stores, it’s mostly poor, white and rural. This is the sort of place that has trended increasingly Republican in recent years.

Why on earth do Nebraska and Maine do this?

You should credit or blame Maine, because it had the idea first. The state adopted the plan — sometimes called the Maine Method — in 1969 as part of a series of good-governance reforms. After the 1968 election — in which Hubert Humphrey badly lost the Electoral College despite nearly defeating Richard Nixon in the popular vote — the idea was that it brought the Electoral College closer to one person, one vote.

Nebraska made the change in April 1991. The proposal’s backers claimed that it gave candidates a reason to visit Nebraska, then as now a solidly red state whose statewide electoral votes are rarely competitive. There are a couple further points of context here, however.

First, 1991 was a time when it seemed like Republicans would win every election for the foreseeable future, having won three in a row under Reagan and Bush. It was to the point where Saturday Night Live ran a skit about the Democratic primary entitled “The Race to Avoid Being The Guy Who Loses to Bush”.

And second, Nebraska — uniquely among the states — has a nominally nonpartisan, unicameral legislature.1 Nebraska’s tradition of nonpartisanship has frayed to the point that every state senator’s de facto party affiliation is now clear. But it used to be a state that elected its fair share of Democrats to statewide office. And in 1991, Nebraska had a Democratic governor, Ben Nelson. As a U.S. Senator, Nelson would later become a frenemy to progressive Democrats by first stymying Obamacare but then later voting for a pared-down version. So blame Nelson for the lack of the public option. But he did help get Obama and Biden one extra electoral vote.

So the Nebraska bill’s going to pass, right?

Republicans are still trying. But probably not.

One holdover from Nebraska’s consensus-driven tradition is that it has a robust filibuster, which Democrats used to substantially delay a 2023 bill on abortion and transgender care for minors. Those efforts ultimately failed, but the state gives a relatively large amount of protection to the minority.

The filibuster has also been used to thwart winner-take-all legislation in the past, with Democrats sometimes having been joined by Republican defectors. That had looked like a moot point this time around because Republicans had controlled only 32 seats, one fewer than the 33 they’d need to overcome a filibuster — until Wednesday when Mike McDonnell switched parties to the GOP. However, McDonnell cited Democrats’ stance on LGBTQ issues, not the Electoral College vote, as the reason for his switch — and he represents Omaha, which would lose its Electoral College leverage under winner-take-all. Furthermore, McDonnell has said the party switch won’t change plans to vote against the electoral college legislation.

A plan to attach the winner-take-all provision to an unrelated bill also badly lost a procedural vote in the legislature on Wednesday. So Democrats are feeling optimistic that they can defeat the change.

Could Maine also revert to winner-take-all?

It’s less likely than you might think.

In principle, Democrats currently control a trifecta in Maine — both branches of the state legislature plus the governorship.

But when I emailed Doug Rooks, a veteran Maine journalist, he was skeptical about the prospects for a change. One problem is the timing: Maine has some filibuster-like provisions for bills that are brought up on an “emergency” basis.

“Even if someone were interested in emulating the Nebraska legislation, it would be difficult if not impossible,” Rooks said. “The Legislature is scheduled to adjourn April 17, and the Legislative Council, which must approve the introduction of all bills in the current ‘short’ session, met on March 28 and is unlikely to meet again before adjournment. If it were somehow approved for introduction, it could only be passed by 2/3 majorities.”

Now, as Drew Savicki points out, there might be some workarounds to this if Democrats were really so determined.

But Rooks was doubtful about the willpower to do this. “I have not heard of any interest in reverting to ‘winner take all,’ and in fact I suspect the opposite may be true,” he said. Maine also has a strong tradition of bipartisanship — routinely electing both Democrats and Republicans to office — and it might not want to mess with its system. Rooks also told me that advocates for electoral reform in the state had mostly focused on adding Maine to the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact — which would pledge all of the state’s votes to the winner of the national popular vote provided that enough other states also joined the compact — rather than undoing the Maine Method.

What if only Nebraska switches back to winner-take-all: could that cost Biden the Electoral College?

Yes. You can draw reasonable maps where one electoral vote switching would make the difference. But I suspect that people overstate the likelihood of this. It is a statistical game of pinning the tail exactly on the nasty spot of the donkey.

To simplify, let’s make some assumptions here:

Absent a rules change, Biden wins Nebraska’s 2nd district and Trump wins Maine’s 2nd district.

No faithless electors or third-party Electoral College votes.

Trump wins in the event of a 269-269 tie. In that case, under the 12th Amendment, the election goes to the U.S. House — but each state delegation gets one vote. The one representative from North Dakota would count as much as the 52 from California, in other words. Republicans are very likely to control the majority of state delegations, especially in a political environment where the presidential vote is close enough to come down to a tie. So a tie means Trump wins, probably.

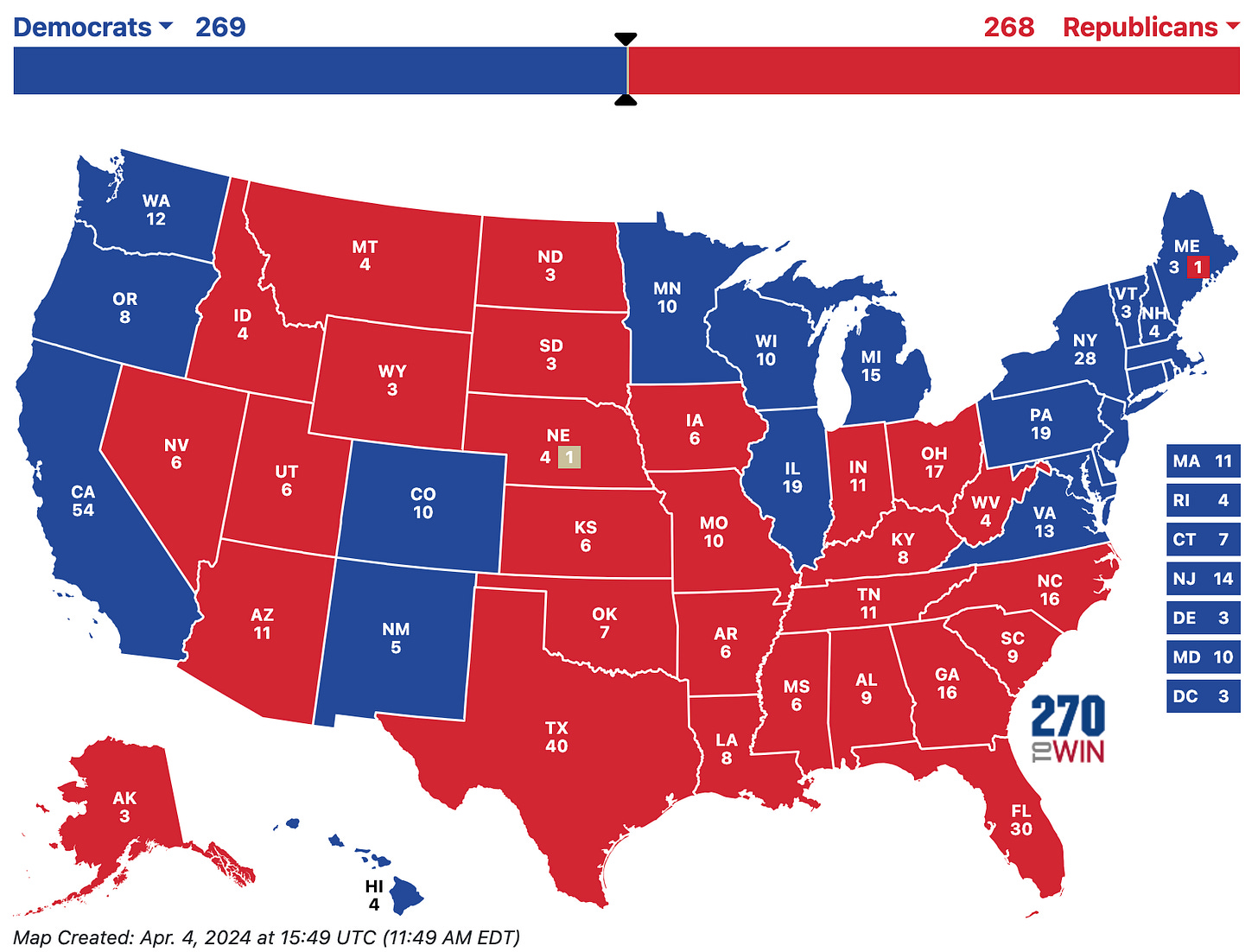

With these rules in mind, I searched for scenarios where Biden would win 270-268 under the current rules, but would fall into a 269-269 tie if he lost the one electoral vote in Nebraska. Assuming every other state votes the same way as in 2020, there are 64 combinations involving the following states — Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — going to either Biden or Trump. Exactly one of those 64 combinations involved a map where Nebraska would flip the outcome:

It’s hardly crazy; this is what happens if Biden holds the former “Blue Wall” states of Pennsylvania, Michigan and Ohio, but then loses the new-fangled swing states of Arizona, Nevada and Georgia. So this is something for Democrats to worry about — although still it’s just 1 out of 64 logical combinations.

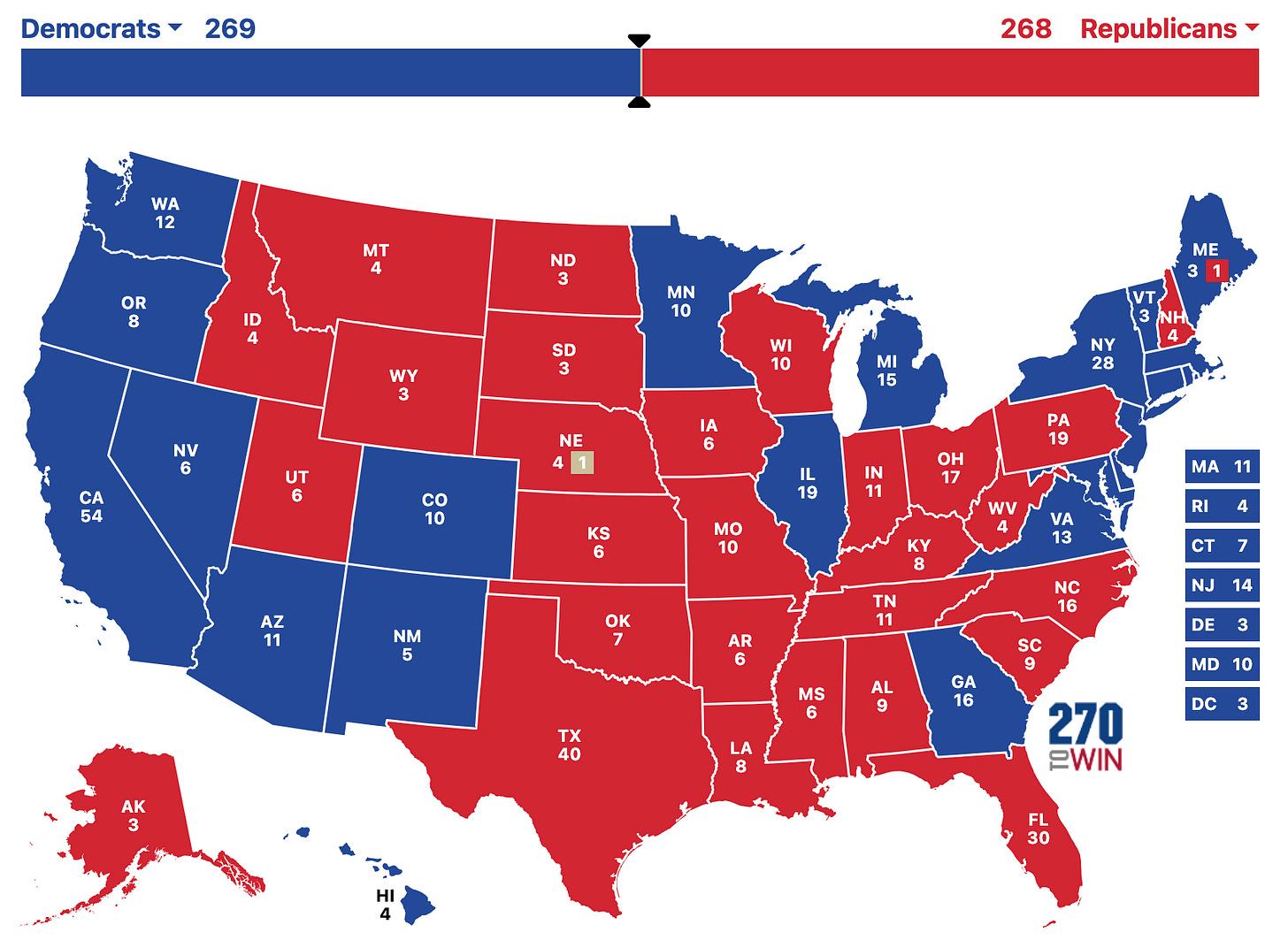

How about if we consider an expanded range of swing states? After the six I already mentioned, these states were closest to the Electoral College tipping point in 2020: Florida, Minnesota, New Hampshire and North Carolina. Considering 10 swing states rather than six radically increases the number of combinations: now there are 1,024 rather than 64. And in 7 of those 1,024 combinations, or 0.7 percent, Nebraska’s 2nd district made the difference. Some of those appear relatively unlikely to my eyes, but in addition to the one I described before, this map is plausible, for instance:

This is sort of the opposite of the map I showed you a moment ago. Biden holds on to Georgia, Arizona and Nevada, but struggles in the Midwest and the Northeast, losing Pennsylvania, New Hampshire and Wisconsin. That map would still be a 270-268 win for Biden with the Nebraska vote, but a 269-269 tie without it.

And what if only Maine switches back to winner-take-all. Could that cost Trump the Electoral College?

Again, yes — though again, it’s relatively unlikely.

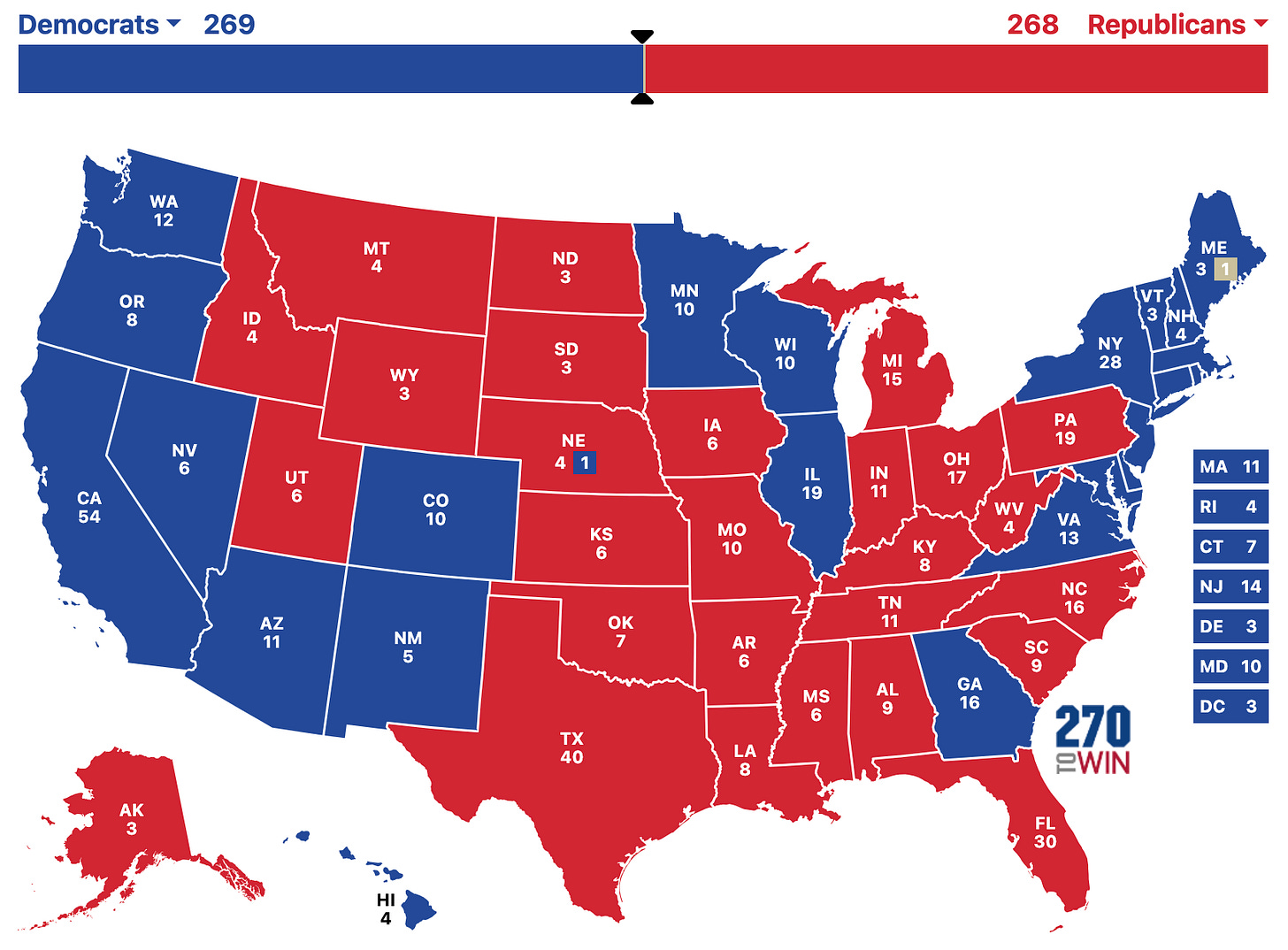

Now we’re looking for maps that would be 269-269 under current rules, but would flip to 270-268 Biden if he won all of Maine’s electoral votes. Among the 64 combinations involving the six canonical swing states — AZ, GA, MI, NV, PA and WI — there was exactly one such map:

It’s a bit weird — this map has Biden winning Wisconsin but losing Michigan and Pennsylvania, even though Wisconsin has recently been the reddest of the three states — but nothing too crazy.

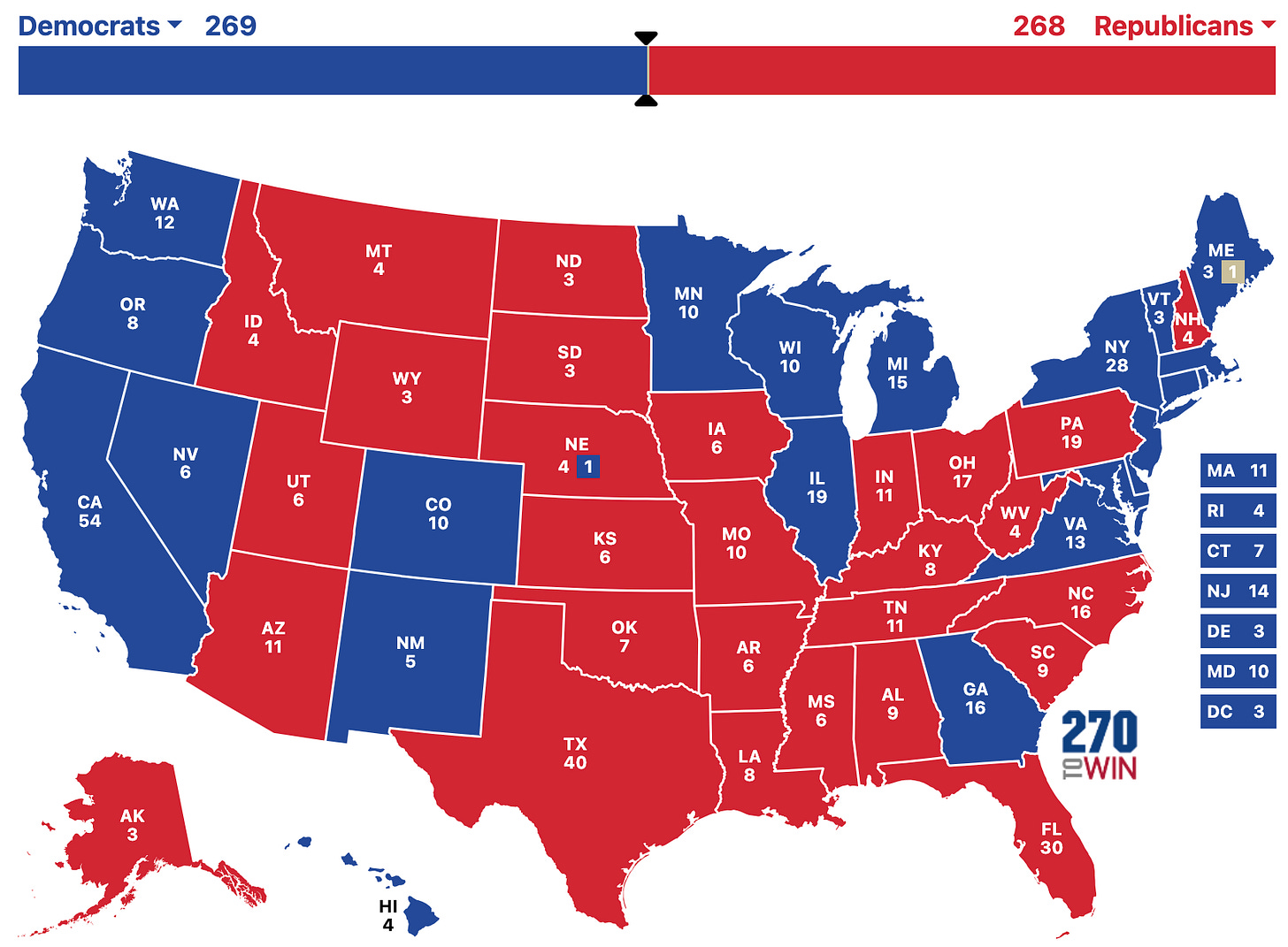

Using the expanded list of 10 swing states, there were 14 combinations out of 1,024 (1.4 percent) where Maine would make the difference. Here’s one involving Biden underperforming in the Northeast and losing Pennsylvania and New Hampshire from his 2020 map, along with Arizona, but holding the other swing states:

What would happen if every state used this method? Would that help or hurt Biden?

First, let’s ask what would happen if every state and district voted exactly the same as in 2020.

Based on estimates compiled by Daily Kos elections using 2024 district boundary lines — which have changed from 2022 in some cases — Biden would win 224 districts and Trump would win 211. And — again, assuming that everything is otherwise the same as 2020 — Biden would win 25 states, plus the District of Columbia, and Trump would win 25. That works out to a Biden win in the Electoral College, 277-261 — a narrow margin despite assuming that he’d replicate his 4.5-point margin from 2020 in the national popular vote.

So does that imply the Maine Method hurts Democrats? Actually, the story is a bit more complicated than that.

Let’s now assume that the popular vote is a tie. We’ll accomplish this by means of a 4.5-point uniform swing toward Trump — that is, every state and district becomes a net of 4.5 points more Republican than it was in 2020. In that eventuality, Biden would win 214 districts to Trump’s 221. And he’d win only 19 states rather than 25, losing Georgia, Arizona, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Nevada and Michigan from his 2020 board. Biden now loses the Electoral College 283-255.

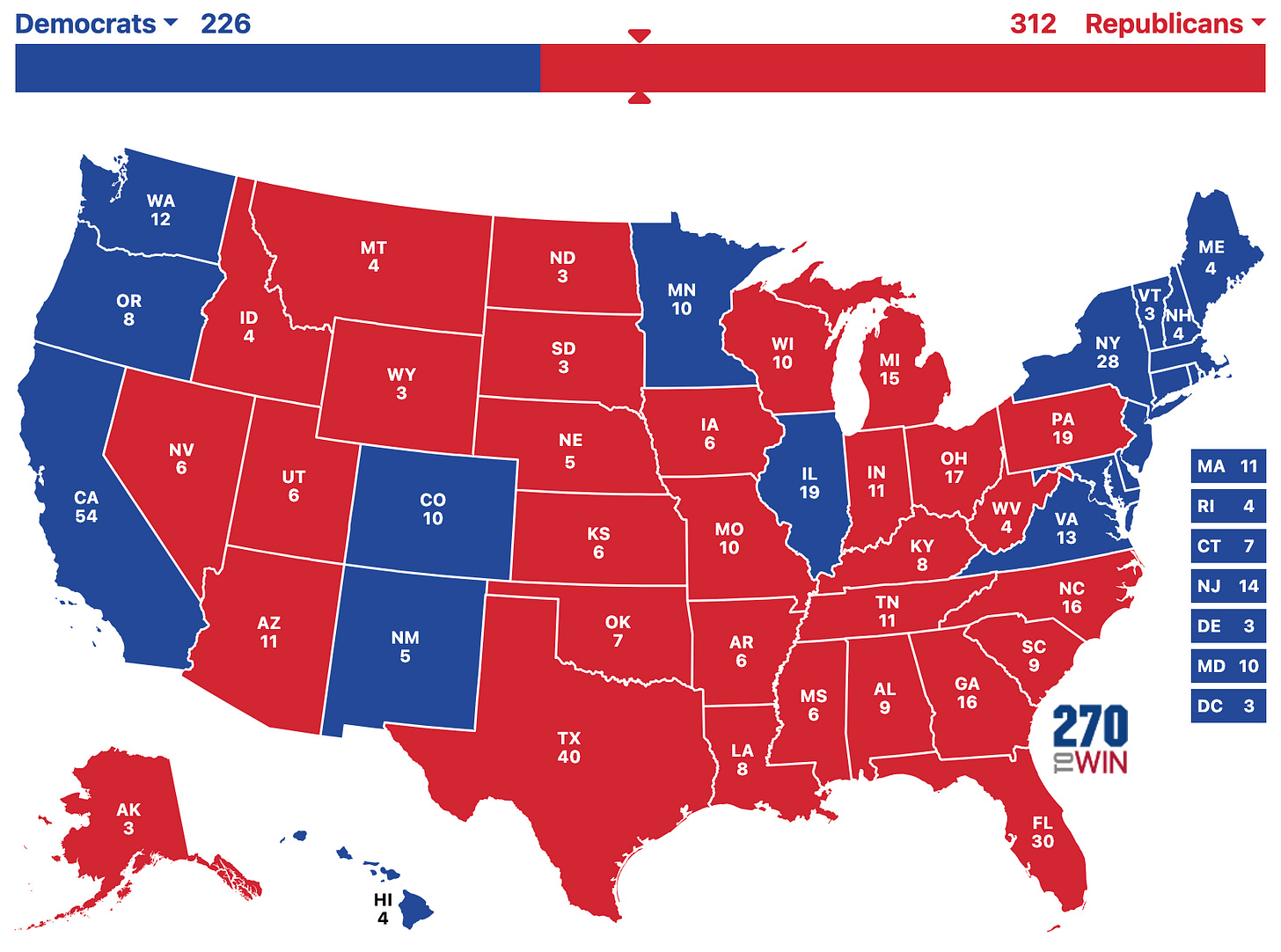

So this method would have a bit of a Republican bias, in other words. However, the bias is less than it would be under winner-take-all rules, in which case Biden would lose the Electoral College 312-226 under a tied popular vote:

We could delve into even more detail about how this would change campaign strategy and so on. But the short version is this: congressional districts do not currently have that much of a bias against Democrats because of the improvements Democrats made in the 2020 redistricting cycle. So if congressional districts were used as a basis for awarding electoral votes, it wouldn’t hurt Biden that much. The Electoral College as currently constructed is a bigger problem for Biden.

Is the Maine Method good for democracy?

OK, bonus question. I think Maine and Nebraska had noble intentions, but I don’t particularly like the Maine Method.

One problem is that, in going by congressional boundary lines, the method leaves a lot up to the redistricting process. And although Maine and Nebraska have rational, fair districts, a lot of states don’t. In some states there’s even a vicious cycle where state legislatures are responsible for setting congressional boundary lines and gerrymander them, but those state legislatures are also gerrymandered. It can be very hard to get out of the trap; it took years for Democrats to do it in Wisconsin, for instance, until they finally elected a liberal majority on the state supreme court. I’d be fine with the Maine Method if paired with redistricting reform, but I don’t like it otherwise.

There’s also the issue of states potentially playing electoral “Calvinball” by making up rules for allocating Electoral College votes as they go, something they have broad rights to do under the U.S. Constitution. Under Republican leadership in the 2010s, for instance, Pennsylvania periodically flirted with allocating its Electoral College votes proportionately, something that could cause a much greater skew than anything involving Nebraska or Maine. Breaking further from the norm of winner-take-all could easily get out of hand.

Meaning just one legislative body, not an upper and lower chamber

Another perspicacious piece by the esteemed and thorough Nate Silver. While Mr. Silver was studying math in high school, I was winning Nebraska state debate championships. I am a Sophist. He is the true Athenian. Watch out for that hemlock. Having worked as the Director of Propaganda and Sophistry for one Jeffrey Lane Fortenberry (Retired U.S. Congressman, CD-1), and born and raised in the Cornhusker State, I can state with some confidence that Nebraska is never changing how it apportions electoral votes. First, that move would kill a key strategic reason for presidential candidates to visit Omaha, home of CD-2 and what we Bugeaters call "The Bacon/Biden" voter. In the 2020 general, Republican House member Don Bacon comfortably won CD-2, even as Democrat Joe Biden also comfortably carried CD-2. The reason for this split ticket is not that cities usually trend Democratic in national elections, even when the Mayor is Republican (as in the case with Omaha's Jean Stothert), but that in CD-2, there are two counties: all of Douglas County (which is Democratic in its urban core), and some of Sarpy County, which is a mixed bag. Sarpy is home to many Republicans and moderate Democrats who presently work or formerly worked at Offutt Air Force Base in Bellevue––which, due to weird redistricting, is part of CD-1)––where General Don Bacon was wing commander. Sarpy is the the heart of the Bacon/Biden voter. Secondly, campaigns spend large amounts of money in the Omaha TV market, not only to win CD-2, but, just as important, to win Iowa in the caucus elections and general. Omaha is right across the Missouri River from Council Bluffs, Iowa. Finally, this election is not going to be close. Democrats are going to win it walking away, despite what current polls indicate. I outlined the reasons here: https://crotty.substack.com/p/joe-biden-has-99-problems-but-trump

I've thought about this before. I think that first map is quite plausible and if that were the difference between Biden winning or Trump winning I'm pretty sure red Nebraska would figure out a way to give all of its electoral votes to Trump (and that Maine wouldn't be able to do the same for Biden). And I don't think courts would overturn it. So in my mind that's a map that's nominally 270-268 Biden but is fairly likely to yield a President Trump.