Can Democrats escape their Florida death spiral?

Why the Sunshine State is no longer a swing state.

After alligators drag their prey into the water, they’ll perform what’s known as a death roll, repeatedly rotating their body 360 degrees to dismember the poor creature in their jaws. Being bitten by an alligator isn’t ideal to begin with, but the death roll makes an already bad situation worse because it disorients the prey animal and makes it harder to fight back or escape.1

The same sort of thing can happen to a political party. A short-term bad beat can easily become a death spiral that turns a well-funded, competent state party into a shell of its former self. The vicious cycle of losing races, losing money, and losing out on quality candidates makes a comeback harder and harder.

Take Florida (whose state reptile, of course, is the American alligator). Republicans have held a trifecta in the state since 19992 and Democrats won their last majority in Florida’s Congressional delegation in 1988. But 25 years ago, it was still the archetypal swing state.

George Bush won Florida by 537 votes in 2000 in a race that came down to butterfly ballots, overseas votes, and the Supreme Court stopping a recount.3 A decade later, Barack Obama carried Florida by not-much-less narrow margins of 2.8 and 0.9 points. But then the losses for Democrats started to stack up:

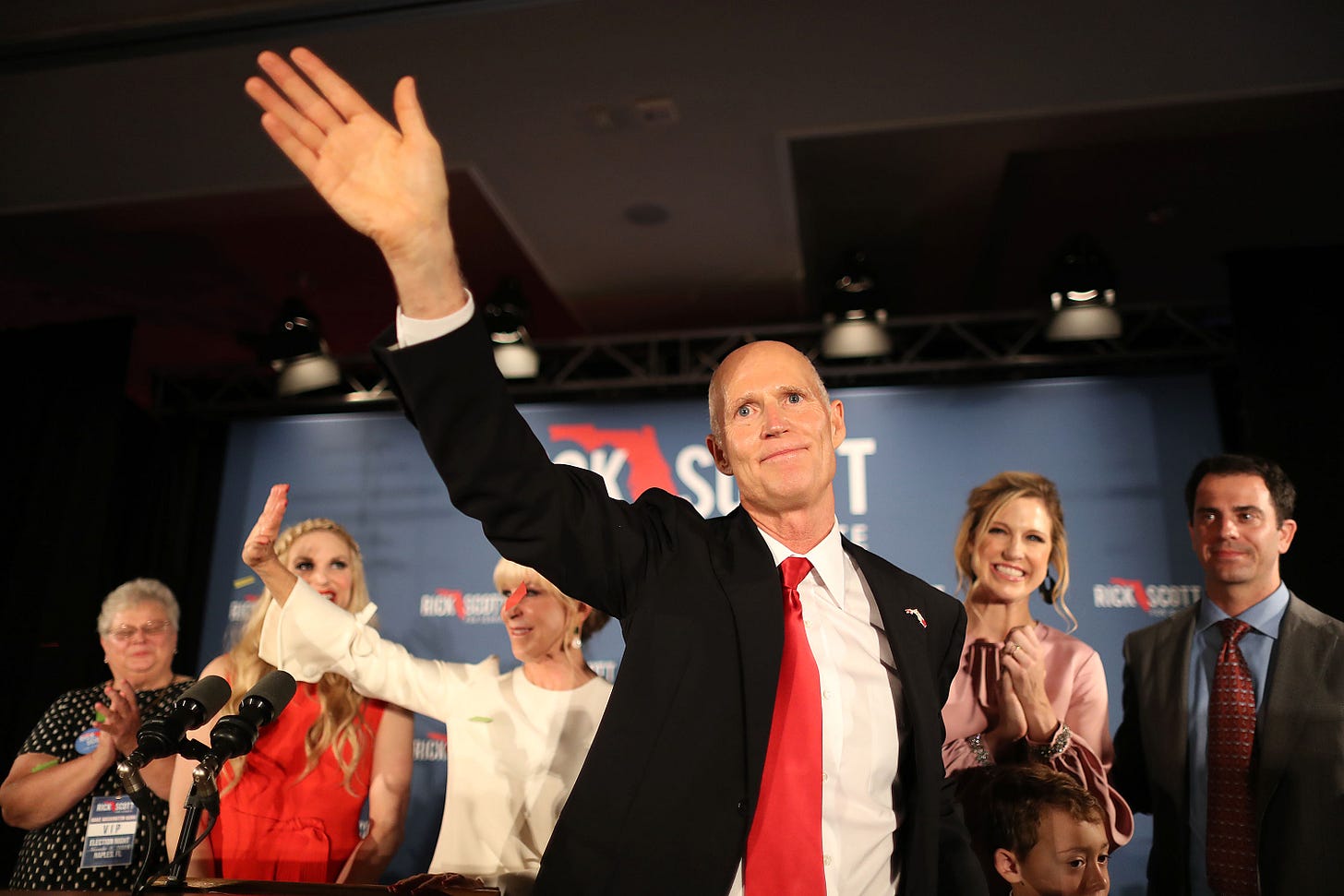

2012 was the last year Florida elected a Democratic U.S. Senator. Incumbent Bill Nelson even lost in 2018 in what was otherwise a strong Democratic year.

Donald Trump has won the state three times in a row, and by a larger margin each time.

Republicans have held two-thirds supermajorities in both chambers of the state legislature since 2022.

If you’re a Democrat, you might look at this data and be tempted to write off Florida as a permanent Republican stronghold. And that’s increasingly the consensus among nonpartisan political observers, too. On paper, Florida is one of a number of “reach states” that could be competitive if there’s a sufficiently large blue wave this November. Its partisan baseline based on our current generic ballot average and the results of recent elections is “just” R +4.9, similar to Iowa, Texas, and Ohio. However, traders at Polymarket give Democrats only a 13 percent chance of winning the Senate race in Florida — less than half their chance in those other states. And for that matter, less than Alaska, which has a partisan baseline of R +8.2.

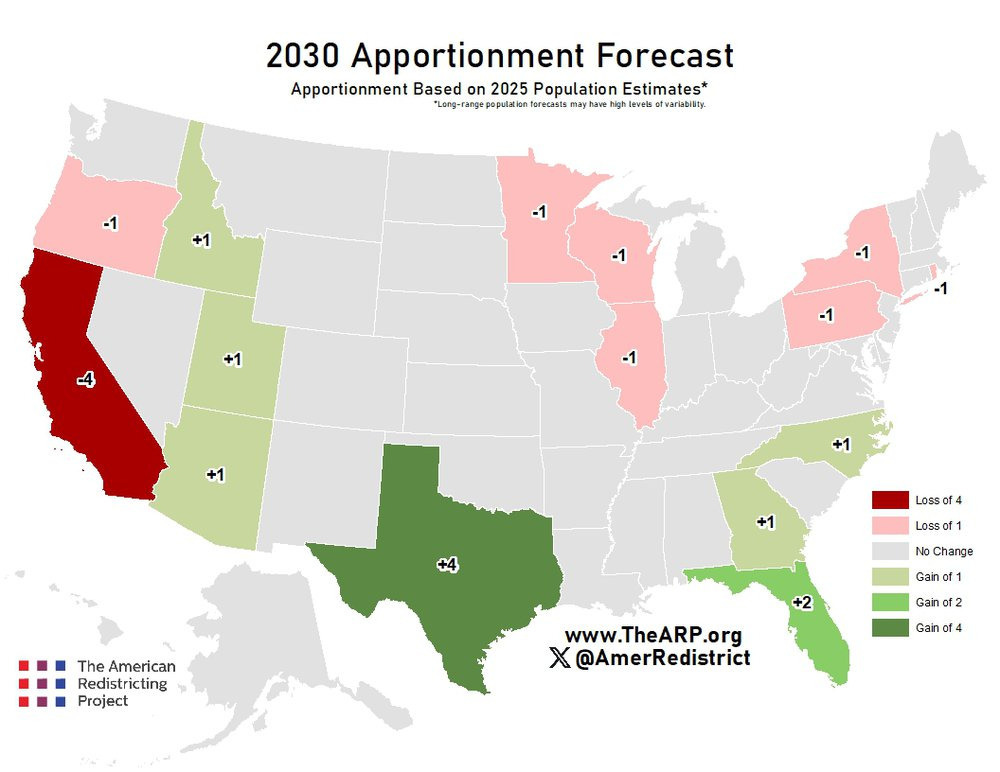

And while Democrats might be happy enough to swap a competitive Florida for a competitive Alaska in their bid to reclaim the Senate in 2026, the Sunshine State is a much bigger problem for their long-term future. Mid-decade projections of changes to the Electoral College map don’t have a stellar track record, but Florida, Texas, and Arizona are projected to gain seats.4 Where will those seats come from? Some combination of shrinking blue states like New York and California, and the Blue Wall.

Democrats will still have their share of winning maps in 2032, but Florida being this far from the tipping point — meaning that it would be competitive only in the event of a blowout where the Electoral College was already secure — considerably constrains their options.

Party registration data has shifted against Florida Democrats

Why the pessimism? Some of it is based on hard data. The percentage of registered Florida voters affiliated with the Democratic Party has plunged from 69 percent in 1972 to just 31 percent in 2025. Part of that decrease was driven by more Floridians registering as “no party affiliation” or with a minor party. (About 29 percent of registered Florida voters fall into that bucket, compared with just 3.4 percent in 1972). But since 2020, the share of Republican registrants has jumped from 35 percent to 41 percent.

These changes reflect both migration patterns and current residents switching parties. Post-COVID, Florida became one of the fastest-growing states in the US. Based on crude stereotyping — Florida is a coastal, very multicultural state — you might expect that to help Democrats. Instead, between 2018 and 2023, about 45 percent of those new residents who were previously registered to vote in another state registered as Republicans in Florida, while only 24 percent registered as Democrats.

But that only explains part of the shift: “some of the migration stuff [has]... been overplayed. It’s obviously been a thing. But there aren’t that many more registered voters today in Florida than there were in 2020,” said Steve Schale, who has worked in Florida Democratic politics since before the party’s collapse. Perhaps the bigger problem for Democrats is that Florida’s heavily Hispanic (especially Cuban-American) and not-very-college-educated population has been an ideal recipe for a red shift in recent years. According to the exit polls, Hispanic voters in Florida moved from D +27 in 2016 to R +16 in 2024. Have Democrats gained ground among white college-educated voters in the state? Sure. But voters without college degrees have moved 16 points toward Republicans over the past three presidential cycles.

Is this all the FDP’s fault?

Still, these partisan registration shifts have happened in other states, too. Schale thinks that “when you look at states like North Carolina… Pennsylvania … [and] a lot of states that have partisan voter registration… you’ve seen things go the wrong way” much like they’ve done in Florida. In 2024, newly registered voters in Arizona were an R +11 group, and in North Carolina, they were R +1.6. But in Florida, there’s been a clearer connection between the voter registration numbers and increasingly poor topline outcomes for Democrats. Why?

I’ll start with a caveat: it’s easy to overestimate how much leverage a state political party has over electoral outcomes. A big part of Florida’s rightward shift would have been nearly impossible for the Florida Democratic Party (FDP) to prevent, no matter how optimally it was run.

But if you read headlines about Florida politics (or, like me, were a political science undergrad in Tallahassee) the most common thing you hear about the FDP is that it’s a complete and total mess full of ineffectual grifters. (I’m barely exaggerating here). Here’s a quick list of facts that might make you question the party’s decision-making:

Their 2022 gubernatorial nominee was former Republican governor Charlie Crist, who came over to the blue side in 2012 (after a brief stint as an independent) and had already run unsuccessfully statewide for the Senate in 2010 and again for governor in 2014.

The person whom Crist beat in the 2022 Democratic primary (Nikki Fried) now runs the FDP.

In 2018, Democrats nominated Tallahassee mayor Andrew Gillum in the gubernatorial race. He lost by only 0.4 points, but that probably came down to an FBI investigation of corruption in Tallahassee City Hall that overshadowed his campaign.5

There’s a steady stream of splashy headlines about Democratic state legislators leaving the party.

Still, the answer is more complicated than “the FDP is run by idiots.” No political party is perfect, and the Republican Party of Florida has its fair share of dysfunction. But at least Republicans are still raising money in the state, while Democrats aren’t.

Intentionally hollowing out your party is bad

In the fourth quarter of 2025, the Florida GOP raised $7.9 million. How much did the FDP raise? A comparatively paltry $1.7 million. The top Democratic contender for Florida governor this year (David Jolly) has raised more than $3 million so far, which doesn’t look bad until you compare it to Republican frontrunner Byron Donalds’ $45 million.

And the GOP’s fundraising advantage isn’t new. Former Florida House member Alan Williams told me that in 2018 — when Democrats nearly defeated Ron DeSantis — “we didn’t have enough resources to get to the finish line, and not only in the governor’s race, but in a lot of the different House races.”

Some of this may reflect poor morale: it’s not exactly surprising that money would dry up when a party goes on a generational losing streak. “I think a lot of that money is being shifted to other states that are in play,” said Williams. If you’re a donor, why would you waste money on yet another Florida loss?

But Florida Democrats have also spent the money they have raised oddly. After Obama’s win in 2008, Florida Democrats made the decision to direct money away from the FDP toward an alliance of donor-backed groups that would work to elect Democratic candidates. According to Schale, who was involved in those talks, the idea was that “if we stand up some… organization that’s focused towards Puerto Ricans, that they’ll understand how to talk to Puerto Ricans better than the Democratic Party ever could.”

These organizations did raise and spend a meaningful amount of money, at least initially. Still, it was probably a poor choice to essentially defund the state party instead of emulating the massive, centralized party operations that helped Obama win the state twice. “We as a state have not built partisan infrastructure, really at all, in any meaningful way,” said Schale.

It’s not that these groups are uniquely ineffective — although they can push the party in a more progressive direction that isn’t always helpful — they’re just the wrong tool for the job. Unlike the FDP, they can’t directly coordinate with candidates, nor can they engage in partisan organizing. Schale said he didn’t “understand why you wouldn’t want to invest in a structure that’s going out and registering voters in a partisan way, having those conversations in a partisan way, and in supporting candidates and building that… kind of field operation that is partisanly-focused.”

Repairing the damage now will require an enormous commitment of time and money, a tough sell when Democrats have so little success in Florida to point to on the scoreboard. Schale told me that when people ask him about running for state party leadership, his first question is “are you going to raise me $10 million? Because if you’re not going to raise me $10 million then what’s the fucking point?”

And when money is that scarce, you need to be especially careful about how you use your resources. What you probably shouldn’t do is spend big on unwinnable races or try to compete for every possible seat. If you’ve picked up on the theme of this article, you’ll already suspect that’s exactly what the FDP tends to do. In 2024, they made a big deal about contesting every seat in the state legislature. We’re “an inch deep and a mile wide as it relates to the resources,” said Williams.

Last year, Democrats raised about $15 million for the special elections in Florida’s 1st and 6th Congressional Districts. Did they overperform? Yes. But they still lost both races, and it wasn’t particularly close. Democrats did get a win in the Miami mayor’s race late last year. But messaging about off-year local victories and overperforming in losses can only get you so far.

Moreover, most of that money came from out of state. For example, after losing his special election in the 6th District, Josh Weil launched a campaign for U.S. Senate. Before dropping out due to a health problem, only 12 percent of individual contributions to his Senate campaign came from in-state donors.

The research we’ve conducted for our midterm model suggests that out-of-state donations provide much less of a positive signal than in-state ones. And that could be a problem for Democrats this year, too. True, Trump impeachment whistleblower Alexander Vindman, who moved to the state in 2023, raised a bunch of cash when he threw his hat in the Senate ring. But it’ll take more than Resistance hype to carry Democrats across the finish line. Itemized data for Vindman isn’t available yet, but searches for Vindman’s name in Google Trends data is about twice as high per capita in D.C. as in his new home state.6

It might be that the party needs to start with a more attainable goal: getting out of the superminority in the state legislature. Picking up the two state senate seats and/or five state house seats needed to make that happen will be easier if money flows mostly to competitive races instead of an everything-everywhere-all-at-once approach.

Any additional leverage in the state legislature is going to be especially important now that Florida is following Texas in a mid-decade redistricting push, with a special map-redrawing session scheduled for April. Florida’s map already favors the GOP, but a new map could put a final nail in the FDP’s coffin by adding another three or so Republican seats.7 Focusing on rebuilding the party from the ground up could also help the Democrats develop a better farm system, rather than relying on retreads like Crist or relatively new arrivals like Vindman in statewide races.

If “getting out of the superminority so we can maybe soften the blow of mid-decade redistricting” sounds like a sad goal, that’s because it is. All of these problems — a lack of high-profile wins, poor morale, bad decision-making, a lack of money, a failure to develop compelling candidates, and Florida’s increasingly entrenched reputation as a red state8 — tend to be self-reinforcing. Hence, the death spiral. It took Florida Democrats a decade to get into this situation. Barring a miracle the likes of which the state hasn’t seen since the 1997 Marlins, it will probably take them a similar length of time to get out of it.

For historical context, I regularly woke up early to watch The Crocodile Hunter on Animal Planet when he was in elementary school.

With a short interlude in 2010 when incumbent Republican governor Charlie Crist became an independent during his final year in office.

Unsurprisingly, Florida was also the tipping-point state that year.

These projections are based on 2025 population estimates.

Gillum was later indicted in 2022 over how he raised and used funds while mayor, but was acquitted in 2023. He was also involved in a separate scandal — in 2020 he was found in a hotel room with “a reputed male escort and suspected methamphetamine.” — but that happened after his gubernatorial bid.

As a former Florida resident who now lives in D.C., I technically contributed to that trend while writing this article.

The Florida Supreme Court recently rejected a challenge to the current map based on its elimination of a majority-Black congressional district in the northern part of the state.

Which may affect who migrates there. Talk to your progressive friends about Florida: it probably isn’t high on their list of places to relocate.

I think all mentions of Andrew Gillum should include the some variant of the phrase the meth fuelled orgy guy.

It says something about candidate selection.

I'm not from Florida, so what do I know, but the best bet may be to lean into 'all politics is local' and focus on building momentum around things like the Miami mayoral win. Building the local infrastructure to support smaller, local races does a few things: it builds and develops your young talent, it starts to build some positive momentum and name recognition for those candidates that actually can impact the lives of their constituents in a meaningful way.

It may be at a point where you turn the state over to a super majority that can't really deflect its failures onto the opposition, while raising up the future from the grass roots.

Are there cases, also, where it makes sense to run 'independents' in the statewide race?