The incumbency advantage is disappearing. Maybe it's the algorithms' fault.

Voters constantly hear that the world is in a state of crisis. It isn't a surprise that they're kicking out incumbents.

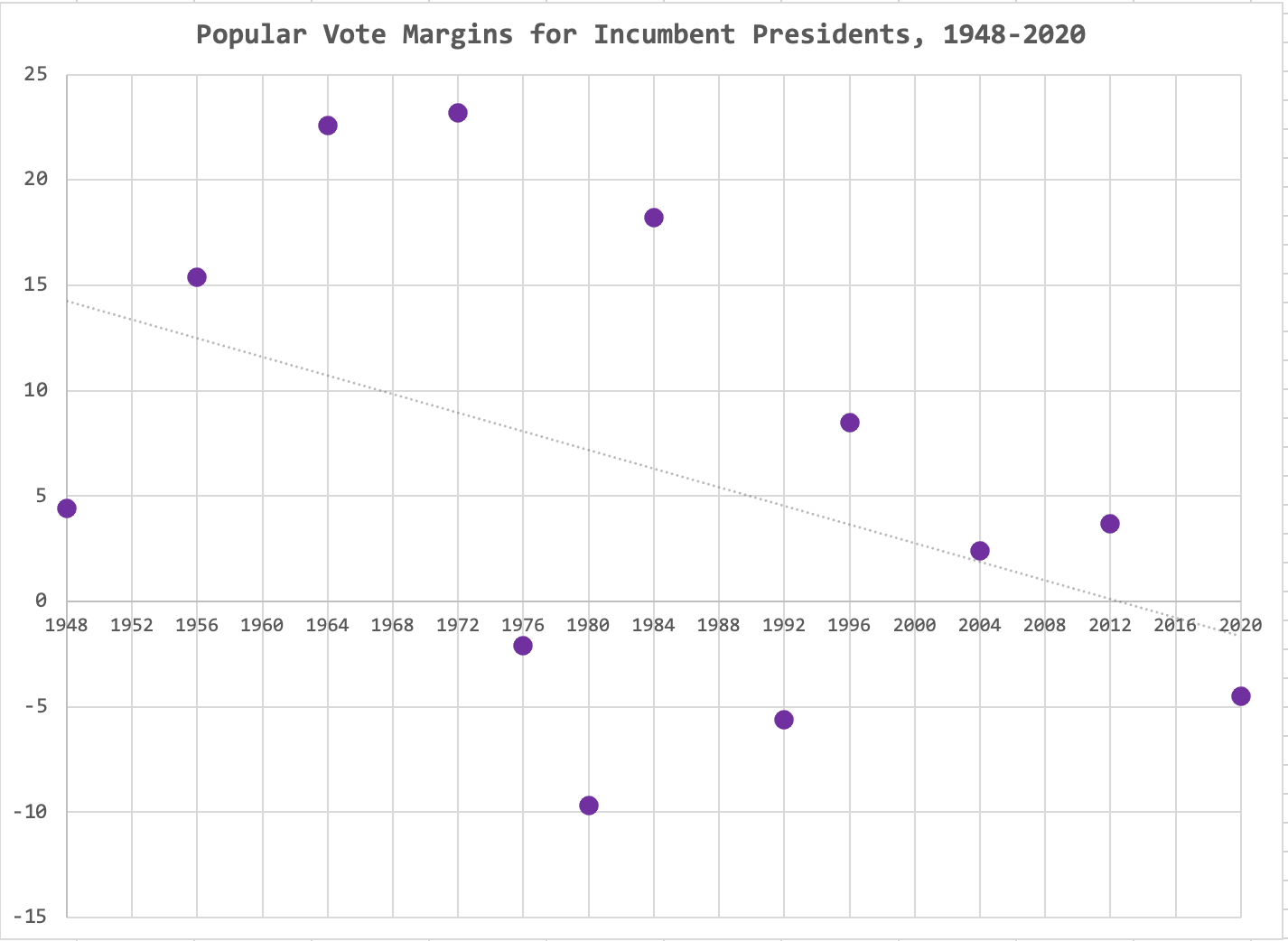

Take a look at the following set of numbers.

-5.6

+8.5

+2.4

+3.7

-4.5What might you say about these? Well, they look pretty darn random, fluctuating haphazardly around zero. Any guesses? Actually, if you looked at the title of this post, you probably figured it out. These numbers reflect the performance of the last five incumbent presidents to run for reelection: respectively, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Bush 41, Barack Obama and Donald Trump. This is what’s left of the vaunted “incumbency advantage”.

Of course, I’m cutting off the data at a convenient place. Here are the incumbent presidents who ran between 1948 and 1984:

+4.4 (Truman)

+15.4 (Eisenhower)

+22.6 (Johnson)

+23.2 (Nixon)

-2.1 (Ford)

-9.7 (Carter)

+18.2 (Reagan)The variance is much higher — which reflects an era of lower partisanship and therefore more swing voters— but the average is substantially positive: +10.3. Here’s what you get if you plot incumbent reelection margins on a chart:

Again, you can cut the data in different ways; whenever we’re analyzing historical election results, we’re unavoidably doomed to jump to conclusions based on small sample sizes. But for what it’s worth, if you plot a linear trend on this data — as in the faint purple line — the incumbency advantage has dipped into negative territory by 2020, meaning you’d rather not be an incumbent than be one.

That’s crazy, right? Don’t incumbents normally have a big advantage? Well, actually I’m not so sure. Earlier this week, Matt Yglesias wrote of the “vast global tide against incumbents”:

I have some theories of my own, but relevant context for any theory is that Justin Trudeau’s polling in Canada is much worse. That could support a story about how political currents in the Anglophone world are tilting sharply against progressives, perhaps a backlash to wokeness and the welfare state. But a Conservative Party is in office in the UK, and their polling is, if anything, even worse than Trudeau’s. Back in October, New Zealand turned out their governing center-left party and the right scored a big win. But in the spring of 2022, Australian voters kicked out a conservative incumbent government and brought the center-left to power.

Arguably this trend is clearer in English-speaking countries, and arguably its clearer for left/liberal/progressive parties.1 But plenty of incumbents of all ideological orientations are unpopular and have been losing elections all around the world — so Joe Biden’s unpopularity doesn’t stand out by comparison. People are pissed off, and they’re taking it out on the people in charge.

What about races for Congress, you might ask? Aren’t the vast majority of incumbents still re-elected? Yes — but a big reason for that is that there are fewer and fewer competitive states and districts.2 There are also selection effects. Members of Congress — say, Joe Manchin — often quit when they think they’re going to lose, and the number of Congressional retirements has been high lately. Without getting too technical here, if you look carefully — such as by running a regression analysis to control for these different factors — you’ll find that the Congressional incumbency advantage has declined quite a bit too.

Blame the media — or the algorithms?

There’s a big debate in political nerd circles right now about why subjective consumer perceptions about the economy are so mediocre even though some of the objective data — especially with respect to the labor market — is strong. One camp says this can be explained by the objective data after all — in particular, lingering voter concerns about inflation, which has abated now but has been very high through Biden’s time in office overall. The other camp says it’s mostly “vibes”: the media spins mixed news in a negative direction. I lean more toward the “this is explicable through fundamentals” side of the argument — I even have a novel theory that algorithmic optimization is sucking more money out of consumers without increasing their utility, basically taking consumer surplus and converting it to corporate profits.

But there’s no doubt that media coverage is relentlessly negative, and I also don’t doubt that this plays a role in the unpopularity of Biden and other incumbents around the world. My beef with the vibes people is that i) the bad vibes are certainly not unique to the economy and ii) nor are they unique to Biden — in fact the mainstream media generally has a left-leaning bias, albeit in a complicated way.

Indeed, some of the people3 who are the captains of Team Vibes have been polemicists on other issues — they’d be among the first people to slam you if you suggested that the COVID data was taking a favorable turn, for instance, or if you didn’t preface every reference to Donald Trump by calling him a fascist or some other epitaph. What’s really going on is that Team Vibes attracts its share of political partisans, and now that we’re entering an election year, they want the media to be at least if not outright friendly to Biden but relentlessly hostile toward Trump.

However, I’m not sure that would actually produce the outcome (Biden’s reelection) Team Vibes desires. Even if the 30 most important editors and producers in the center-left media — at The New York Times, The Washington Post, CNN, etc. — got together and said we must ensure Biden wins by any means necessarily, our credibility be damned — the power isn’t necessarily in their hands:

First, there’s a lot of competition. If certain media outlets were in the tank for a certain candidate — frankly, it’s not usually that hard to tell — some voters would lose trust in them and seek out alternatives.

Second, a lot of decisions are made by algorithm or assisted by data. Even if the party line is “promote good news about the economy”, an editor might notice that an article on the rising cost of child care was performing fantastically well and promote it higher on the home page. In general, stories that promote negative emotionality tend to click better than those that give off positive vibes.

Third, there are the effects of social media, which can take people to very dark places. Social media outlets — not The New York Times — is where most young people get their news.

Fourth, there are the political campaigns and expressly partisan actors, and they know that polemicism sells, too. Donald Trump’s acceptance speeches at the 2016 and 2020 Republican Conventions were extremely dark, telling Americans of a country that was being overrun by and crime, immigration and ruined by corrupt elites. But Biden’s messaging in 2020 was also highly polemical, speaking of four historic crises (COVID, the economy, racism and climate change) at once.

Meanwhile, all of this might get worse because of artificial intelligence which can microtarget and misinform voters — this is something the now-restored CEO of OpenAI CEO, has been worried about. Personally, I don’t know that I see this as a step-change so much as the continuation of a trend: algorithms are constantly getting smarter and more efficient. Because negative sentiment tends to motivate people to vote and motivate them to click on news articles, more efficiency means more negative sentiment — and that has to be bad news for incumbents.

Indeed, if you go back to that chart of how incumbent presidents performed, the incumbency advantage tracks a change in the composition of the media landscape. The period from the end of Wold War II through the early 1990s is generally considered (very much for better or worse) the heyday of “objective” nonpartisan American journalism, before the widespread adaptation of cable news, talk radio or the Internet. There wasn’t much competition, and profit margins were higher, so there wasn’t as much need to optimize around every story (and publishers didn’t have the data to do it anyway). Back then, if the 30 most important editors and producers got together to push a certain party line, perhaps they would have been effective at doing it. News was more curated, more driven by editorial decisions. But that isn’t true of the modern era — which is more ruled by revealed consumer preferences. Nor really is it true of the period that preceded it (incumbent margins tended to be low during the yellow journalism era).

This isn’t to take responsibility entirely out of individual journalists’ hands. Newsrooms tend to be staffed by people who are young, college-educated and liberal, characteristics that are associated with negative emotionality — a polite way to say neuroticism. But even if they mistake pessimism for wisdom, they’re right about one thing: negativity does tend to click well.

Neither of which, I should note, helps Joe Biden as the head of a progressive party in an English-speaking country.

If, for instance, 10 incumbents lose out of 60 competitive districts, that’s different than when 10 incumbents lose out of 120 such districts, even though the overall number of incumbents turned out of office is the same.

Illway Ancilstay

"if you didn’t preface every reference to Donald Trump by calling him a fascist or some other epitaph."

I think the word you're looking for is "epithet", though it may end up being his epitaph as well.

There is some survivorship bias in your pre 1992 data, I think. Both Johnson and Truman elected not to run again because of their unpopularity. Their potential second runs are not counted in the data, yet they almost certainly would drag the incumbency advantage down had they run.