I loved my time in the UK. But it needs an AC intervention.

A stiff upper lip and a warming climate make for a strange combination.

Eli and I will be conducting a rare live edition of Silver Bulletin Subscriber Questions on Monday at 1 p.m. There’s still time to submit questions in the comments of SBSQ #24. Questions about how the shutdown is going? Our philosophy for running the site? Our new NFL model? Please join us in the Substack App on Monday — or if you miss us, we’ll publish a video and transcript afterward. —NS

I recently returned to the US after spending the last year living in the United Kingdom, where I completed a master’s degree at the London School of Economics. I’ll preface the rest of this newsletter by saying that I really enjoyed my time in Europe. London is a fun city, and I have good things to say about pretty much everywhere else I visited in the UK. And no, I’m not just saying that because 4 percent of our subscribers are British.

But for two countries that famously have a brotherhood — even a Special Relationship — the UK and US are increasingly diverging economically. When my boss, Nate, spent his junior year abroad in London in 1999 (two years before I was born1), US GDP per capita, adjusted for inflation, exceeded UK GDP by about $12,000. Now, the difference has nearly doubled to $23,000. But what does that feel like when you’re on the ground? Is the grass really less green on the other side of the pond? Especially in London, which is much, much richer than the rest of the UK?

I attended college in Tallahassee, Florida, which isn’t exactly posh. Still, there was one area where the UK — and Europe more generally — stood out negatively when compared to the US: day-to-day convenience. There are lots of little (and not so little) perks most American households enjoy that are much rarer in the UK. Individually, they seem trivial, but when tallied up, they can result in meaningful quality of life differences. Here’s a non-exhaustive list of examples:

Clothes dryers are less common. About 80 percent of American households have one compared to 60 percent of UK households.

Refrigerators and freezers are smaller in Europe. YMMV, but the refrigerator in my London flat was only slightly larger than the mini-fridge in my freshman year dorm room.

Sink garbage disposals don’t really exist in the UK. That’s partly because of the UK’s stricter environmental and waste disposal regulations.

Rubbish bins — in other words, garbage cans — tend to be smaller in the UK. And many UK localities collect garbage fortnightly (one of my favorite Britishisms) instead of weekly.

It’s hard to buy even simple kitchen knives in the UK. The Crime and Policing Bill currently under consideration in Parliament would mandate that online retailers collect an identity document and a photo to verify customers’ ages before ordering a knife.2 But at least, Parliament is keeping the streets safe from ninjas.

Businesses are more likely to be closed on Sunday in the UK. In fact, large retailers in England can only open for six consecutive hours between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m. on Sundays.

Businesses are now prohibited from offering free refills for sufficiently sugary beverages like Coca-Cola. Why? To help the National Health Service save money spent on treating obesity related health complications.

Most of the time, you don’t notice these little differences. But there are edge cases when the UK’s petty inconveniences can become a bigger problem. Air drying your laundry is fine until you need to clean an item of clothing quickly. And infrequent trash collection isn’t a problem 95 percent of the time. But when disposing of more waste than usual — say, for instance, because you’re moving back to the US — you’ll be playing trash Tetris to make everything fit into your garbage bin the night before your flight.

Let’s be clear: these complaints are nowhere near the top of the UK’s list of problems. Stagnant economic growth, high inflation, an eroding role as a global financial center, and some genuinely startling free speech issues come to mind as more pressing concerns. But small inconveniences are the things expats experience most frequently, and they’re easier to spot than falling IPO volumes.

And there’s one inconvenience that isn’t particularly small: air conditioning. It’s no secret that Brits love to talk about the weather. And when you’re an American, especially one who previously lived in Florida, you’ll get lots of questions about how you’re coping with all the rainy, grey days and the early darkness in winter. But my biggest complaint about the UK’s weather, by far, was the heat.

That might seem odd: the average July temperature high in London is only 73 degrees Fahrenheit, and the Brits consider anything above 82.4 degrees to be a “heatwave”. But there’s a reason these temperatures are hard to handle: Brits simply don’t cool their buildings. Buildings, mind you, that were generally built to retain as much heat as possible in cold winters. Estimates vary, but somewhere between 5 percent and 20 percent of British homes have air conditioning, compared to about 90 percent of US homes.

As with the trash-collection-style inconveniences, you don’t notice the lack of AC most of the time. But it can cause real problems during the summer. Once indoor temperatures break 73 degrees Fahrenheit, sleep quality, work productivity, and even learning in school begin to suffer. (And productivity isn’t exactly the UK’s strong suit to begin with.) If you’re older or have a health condition, the stakes are higher: actually, you might just die. Death rates climb much faster in European cities relative to equivalent places in the US during heatwaves. In fact, according to one estimate, the yearly death rate per 100,000 people from heat in Europe is almost twice the death rate from guns in the US.

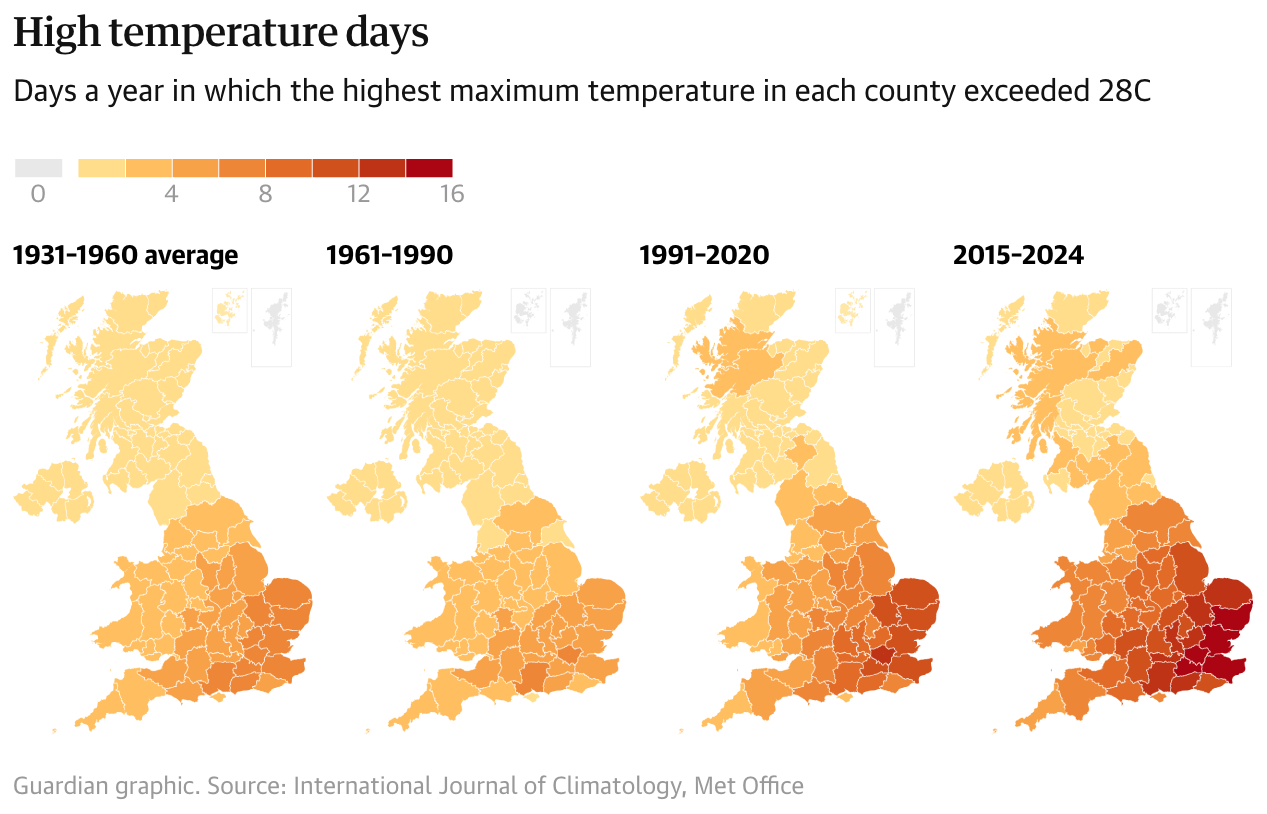

There’s got to be a good reason for the UK’s lack of AC, right? The rationale used to be that England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland are too far north and therefore too cool to need air conditioning. But climate change has pretty much invalidated this argument, at least in the southern parts of the British Isles. The mean annual temperature in England rose from 47 degrees Fahrenheit in 1980 to 51 degrees in 2024. And the number of heatwaves — however liberal the Brits are about defining them — is on the rise. Unsurprisingly, European heat-related deaths are also increasing.3

Brits have noticed the heat and are purchasing more AC units, but adoption isn’t really keeping up with the climate. By some estimates, AC uptake in the UK will only increase to around 30 percent by 2050. And despite record-breaking temperatures this summer, a July YouGov poll found that 61 percent of adults in Great Britain said they hadn’t looked into purchasing a method of cooling their home — not even a fan.

Why? A combination of traditionalism, a stiff upper lip, and concern for the environment. Because it hasn’t been necessary historically, a surprising number of Brits still see adopting AC as a kind of wasteful American-coded extravagance that harms the environment. Sometimes, though, people making this argument horseshoe themselves into downplaying climate change. Here’s an example from The Guardian:

Just as wood burners are being phased out as we start to fully understand the damage they do to climate and also lung health, we now need to consider a ban on some air-conditioning units – particularly when used at the mildest of warm temperatures. And until then it’s up to us not to buy them.

When it’s 26C outside, the average British home simply doesn’t need air-conditioning. It might feel nicer, but making you a little more comfortable isn’t the government’s job. Preventing further damaging climate change most certainly is. For healthy people, let’s not pretend this new trend is anything other than extravagance. Air conditioner [sic] sets you back at least £80 a month to run every night in a single bedroom. Compare that with just under £5 a month to run a classic fan by the bed.

Certainly, 26C (about 79F) isn’t so hot, but the number of days above that threshold is increasing. And remember, this is a country that sends pensioners money every winter to help them pay for extra heating costs. Plans to lower the income cap for this benefit had to be mostly reversed after considerable backlash last year, so the Brits clearly recognize the danger of some temperature-related deaths.

But in some parts of the UK, like London, extreme heat can be more dangerous than extreme cold. Researchers in the UK’s Office for National Statistics found that mortality risk in London when temperatures hit 29 degrees Celsius (84.2 Fahrenheit) is about three times the mortality risk at optimal temperatures (around 67 Fahrenheit). In comparison, mortality risk at 23 degrees Fahrenheit is 2.3 times the risk at an optimal temperature. And to be clear, there’s convincing evidence from the US that widespread AC adoption would substantially reduce these excess heat-related deaths.

While no one in the UK is arguing that the government should restrict access to heating during the winter to reduce carbon emissions, that’s the most commonly cited rationale for opposing widespread AC adoption. AC uses electricity, which — despite the UK’s plans to reach net zero emissions by 2050 — mostly still comes from fossil fuels. But arguments against AC sometimes drift into other progressive critiques: for example, the concern that AC adoption would increase inequality because wealthy people would have an easier time affording it. Other anti-AC takes are just plain dumb, like the myth that air conditioning can make you sick.

To be fair, there are also real challenges: running the AC in the British summer isn’t cheap, given the country’s sky-high energy prices. (UK consumers pay more for energy than those in any other country in the world.) Concerns over cost would be a completely understandable reason for an individual to forgo installing an AC unit.

Still, the bigger problem is that in the UK and elsewhere in Europe, governments are putting a finger on the scale against AC. For example, you can get a grant of up to £7,500 in the UK if you replace your fossil fuel heating system with a more environmentally friendly heat pump. But heat pumps that provide both heating and cooling aren’t currently eligible under this scheme.4 And British local councils frequently reject applications to install AC systems for aesthetic or environmental reasons, or sometimes because they simply don’t believe the home will get too hot during the summer.

This is where the UK’s lack of AC turns from a personal choice driven by traditionalism and/or frugality into a politics of sacrifice. The way to fight climate change under this degrowth-style framework is for people to reduce their consumption and go without things that make life easier and safer. It’s not just the AC. One of the main reasons trash is frequently collected fortnightly instead of weekly is to reduce waste and encourage recycling. OK, fair enough. But this summer, the British government recommended that people delete their old emails, photos, and files to conserve water (yes, really).

This attitude is why, instead of AC, climate-conscious Brits propose solutions like passive cooling (such as shutters and natural ventilation) or even simply slowing down during the midday summer heat. London requires building planning applications to follow a “cooling hierarchy” that puts AC right at the bottom. And the hierarchy doesn’t just recommend trying other things first, it outright discourages AC use: “The increased use of air conditioning systems is generally not supported, as these have significant energy requirements and, under conventional operation, expel hot air, thereby adding to the urban heat island effect.” In a city that already suffers from a lack of affordable homes (and homes in general), making builders conduct an overheating risk assessment before installing AC won’t bring down the cost of housing.

These policies also trickle down to public health. Southwark (the London borough I lived in) released a 2025 “Hot Weather and Health Strategic Needs Assessment” that identified the borough (along with most of inner London) as “the highest risk area in the UK for overheating” but still called for AC as a last resort only. Instead, it fell back on passive cooling and educating residents about ways to stay cool that might have been cool a century ago, like closing shutters during the middle of the day and opening windows in the evening. Did I do these things? Yes. Was my flat still way too hot? Also, yes. And I was able to leave my windows open overnight because I was fortunate enough to be in a 4th-floor flat. Londoners on the 1st floor are out of luck on that front.5

Call me an Abundance-pilled American, but it seems like there’s a better solution that will reduce emissions (and make AC more affordable): build more renewable energy.

AC is becoming a big political issue

Unsurprisingly, this approach isn’t as simple as I’ve just made it sound. First, the UK doesn’t just need to build more renewables, it also needs to modernize its grid to handle increased energy generation. At the moment, excess energy storage capacity lags behind renewable energy generation. For example, on October 1st, Britain’s electricity operator paid wind farms more than £1 million to turn their turbines off to avoid overloading the grid. Second, the British public might resist the Energy Abundance approach. While the environment is nowhere near Brits’ list of top issues facing their country, a May YouGov poll found that 45 percent would prefer an approach to fighting climate change focused on reducing resource consumption. That’s compared to 35 percent who think developing technological solutions to climate change is the better way forward.

But still, politicians in the UK and elsewhere in Europe would be wise not to tie AC adoption to renewable energy goals. Why? Because asking people to go without something (whether it’s economic growth in general or a smaller item like AC) to serve a potentially amorphous long-term goal will probably not be a long-term winner. Especially as the UK continues to get warmer.

And if one political party won’t let people install AC, another one will almost certainly use the issue to its advantage. France gave us an excellent example this past summer. Marine Le Pen (the leader of the country’s right-wing National Rally Party) said she would implement a “major air-conditioning equipment plan” if her party came to power, while the left-wing publication Libération called AC “an environmental aberration that must be overcome.” It might be irrational — but in the midst of a heatwave, I can understand why voters would have picked pretty much anyone promising AC.

There are also non-political costs to delaying AC adoption. It’s becoming an economic liability for the UK, and when the non-air-conditioned Tube reaches temperatures deemed too hot to transport cattle, safety for humans becomes a real concern. Far from reducing inequality, a lack of AC in homes, public transportation, and buildings means that older people or those with health conditions are just out of luck during summer heatwaves. Making the poor hotter just so the rich are also less cool doesn’t help anyone.

We wouldn’t be so presumptuous as to tell the 4 percent of you who are reading this from the UK what to do. But if your former Silver Bulletin London correspondent had to do anything over again after his year abroad, it would be this: find a flat with AC.

Nate is old.

It’s also difficult to donate knives to charity. I had to throw out my kitchen knives and even regular butter knives when leaving the UK because none of the charity shops in my area would take them.

On the bright side, we got fun headlines like “Hot summer causes headache for conker contest.”

Luckily for Brits, that might change soon.

Window screens also aren’t really a thing in the UK, so opening your windows at night when the lights are on inevitably turns your flat into a gathering place for every insect within a two-mile radius.

I was like, this is the dumbest thing I'm going to read today:

>For example, you can get a grant of up to £7,500 in the UK if you replace your fossil fuel heating system with a more environmentally friendly heat pump. But heat pumps that provide both heating and cooling aren’t currently eligible under this scheme.⁴

Then I got to this, and I was like, THIS is definitely the dumbest thing I'm going to read today:

>Window screens also aren’t really a thing in the UK

Someone save this poor culture from itself.

The problem is that leftists (and alas that’s the UK these days) don’t see climate change as a technical problem, or an unfortunate side effect of progress. If they did they’d be all in on nuclear power. Instead, they see climate change as the result of sin — we have become overweening in our mastery of nature — and no solution is acceptable if it does not impose hardship and atonement.