The hottest club in the Electoral College is North Carolina.

It’s the first state to begin any form of early voting — county officials will begin mailing out absentee ballots next week! The Cook Political Report just moved North Carolina from “lean Republican” to “toss-up”. And in the Silver Bulletin model, it’s the third-most-likely tipping-point state, surpassed only by Pennsylvania and Michigan. If Kamala Harris wins it, she’ll have a 97 percent chance of winning the Electoral College. The probability nerds in the audience will note that it isn’t technically a “must-win state for Donald Trump — 3 percent chances happen — but close enough.

In fact, in our model, Harris’s polling average is slightly better in North Carolina than in its neighbor Georgia. The forecast component of our model is slightly skeptical about this and sees them as co-equals: it gives Harris a 38.5 percent chance of winning the Tar Heel State and a 37.4 percent chance at the Peach State. But is it really plausible that she could win the former and not the latter, given that things worked out the other way around for Joe Biden four years ago?

The short answer is yes, sort of. There’s an 86 percent chance that the states will vote together, the model thinks — that either Harris or Trump wins both. But the states aren’t exactly alike, although they’re highly similar. And North Carolina was the bluer of the two until 2020.

Let’s bust out a Steph Curry vs. Magic Johnson-style tale of the tape: a Street Fighter battle between these kissing cousins.

Granted, the model doesn’t use any of these characteristics — other than what we call the “political region” of the states1 and, of course, the number of electoral votes. But I just wanted to articulate a few of the essentials. North Carolina can’t keep up at football, but it does beat Georgia in barbeque and Silver Bulletin subscribers. (There’s still time to catch up, Georgia!) And there’s a surprising lack of elite NBA talent from Georgia. The best player to hail from the state is probably Walt Frazier, but Anthony Edwards has a chance to surpass both him and Dwight Howard. On the other hand, while North Carolina might have invented flight, I’d rather be stuck on a layover at ATL than CLT.

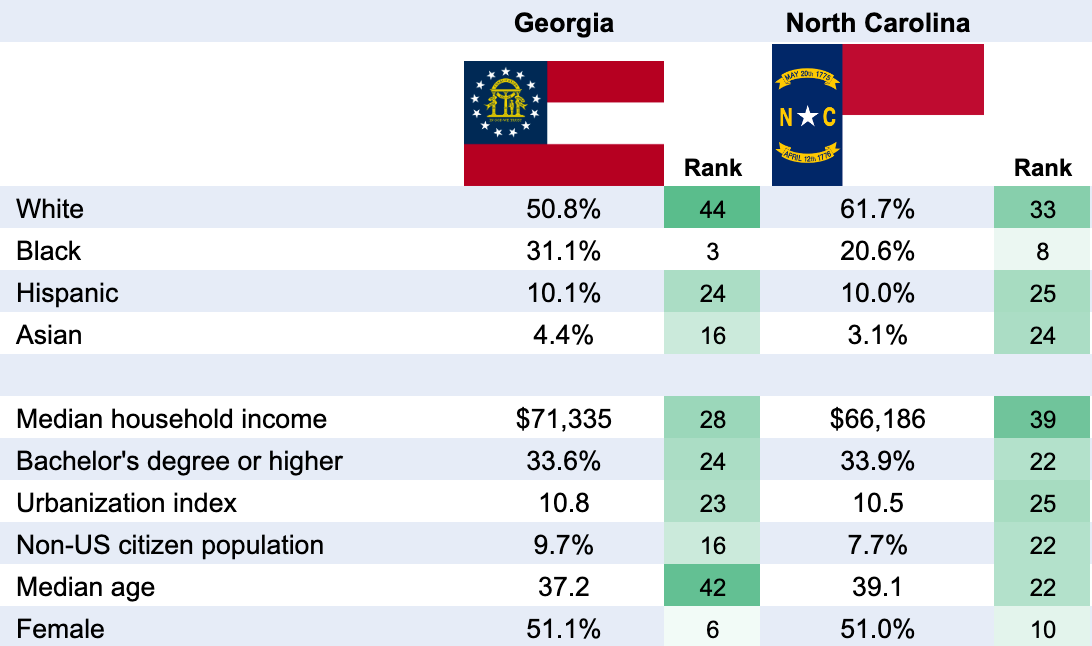

Let’s turn to some of the categories the model actually does use in figuring out how the vote in each state is correlated — a vital factor in avoiding overconfident predictions. (It’s a big mistake to treat the election as 50 independent contests.) Here are their major demographic characteristics, along with their rank among the 50 states:

There’s one big difference to notice right away. Although both states are racially diverse — the “non-US citizen population” category is a proxy for immigration, and both North Carolina and Georgia are above the median — North Carolina is quite a bit whiter. That’s one reason Nate Cohn and other analysts think NC could revert to being bluer this year. Biden was badly underperforming typical Democratic numbers among Black, Hispanic and Asian American voters, and while Harris has closed the gap, there could still be a relative shift versus 2020. Georgia is also younger and wealthier.

Next, let’s look at religious demographics, which the model considers in quite a bit of detail:

In the case of North Carolina and Georgia, there aren’t really appreciable differences — but still I think religion is a factor that’s often ignored by the highly secular East Coast press corps. And this data contains some interesting wrinkles. The primary source is the Association of Religious Data Archives, and it looks toward people who are active adherents, i.e. practicing in some way — it’s not enough to merely identify as religious on a survey. Even in the South, the most religious region of the country, almost half of people aren’t regularly going to their church, temple, mosque, etc.

Because I know it may look odd, the “Muslim + Arab American” category is a compromise of sorts: it combines the number of Muslim adherents with the Arab American population in each state. These categories overlap less than you might think. We added them, along with Jewish religion/identity (which also is complicated) at a time when it looked like the war in Gaza could be an especially important factor in the election: we wanted to account for possibilities such as a rightward shift among the substantial Arab American population in Michigan that wasn’t as relevant elsewhere in the Midwest.

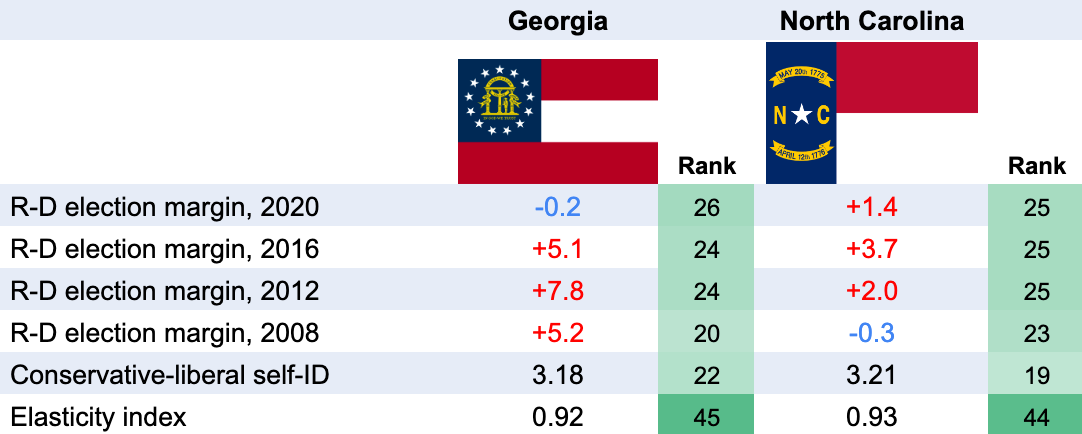

Finally, here are the states’ vital political characteristics:

Technically, the model only uses data from the previous two elections (2016 and 2020) but I’m including 2008 and 2012 as well as a reminder that Barack Obama actually won North Carolina in 2008, and it was bluer than Georgia until the last election. People probably overestimate the degree to which states “trend” in one direction instead of there sometimes being mean-reversion. North Carolina is a good example of this: after trending strongly toward Democrats in 2008, the party has consistently lost presidential and Senate elections there ever since. Still, the Georgia-North Carolina gap was smaller than you might remember in 2020: Biden almost lost the former and almost won the latter.

Both Georgia and North Carolina are more conservative than you’d infer from their purple-state status, as measured by voter self-identify on a liberal-conservative scale in the Cooperative Election Study. You can see that on issues like neither state having legalized weed (even for medical purposes) despite that having become a fairly mainstream position. Remember, both states are relatively religious, and both have a high share of Black voters, who often identify as socially conservative even if they vote for Democrats.

Finally, both states are relatively inelastic, meaning that we don’t expect them to swing as much as other states do. A 1-point shift in national polls would only translate to about an 0.9-point shift in North Carolina and Georgia, the model thinks. The reason is that both states are electorally bifurcated between conservative voters (e.g. evangelical whites) and liberal ones (e.g. young professionals, college students and Black voters) without a lot in between. These are states where each party has a relatively fixed number of voters and turning them out is at a premium — persuasion is comparatively less important.

Overall, though, Georgia and North Carolina are pretty damned similar. In yesterday’s model run, their outcomes had the 16th-highest correlation (.89) among the 1,225 state pairs2. These were the only combos that beat them, which I’ll list in alphabetical order because many of the numbers were really close and subject to some degree of random variance3:

Arizona-Nevada

Arizona-Texas

Florida-Texas

Idaho-Wyoming

Maine-New Hampshire

Michigan-Ohio

Michigan-Pennsylvania

Michigan-Wisconsin

Minnesota-Wisconsin

New Hampshire-Vermont

North Dakota-South Dakota

Ohio-Pennsylvania

Ohio-Wisconsin

Oregon-Washington

Pennsylvania-Wisconsin

Note that correlation is not quite the same thing as political similarity. For instance, the model expects New Hampshire and Vermont to move in same direction — if Harris gains ground relative to Biden in New Hampshire, she’ll probably gain ground in Vermont — but the latter state is obviously much bluer. Still, while Georgia and North Carolina aren’t quite Minnesota-Wisconsin peas-in-a-pod, they have about the same mix of urban, suburban and rural areas, and they tend to vote similarly.

In fact, the model reckons, there’s an 86 percent chance they vote identically this time around, with either Trump or Harris carrying both:

But you don’t need to think back too far to find examples of elections where they split their votes (2020, 2008) — and that’s why both count as battlegrounds.

This differs in some cases from a state’s Census Bureau region, and some states are divided between regions. Maryland is technically in the South, according to the Census Bureau, but it behaves like a Northeastern state politically.

Ignoring Washington D.C. and the congressional districts in Maine and Nebraska.

We run 40,000 simulations per day.

Regarding GA and NC being conservative. . . speaking as an NC resident, it could be that we don't have things like legal weed because we're conservative. Or it could be because our state legislature is heavily gerrymandered and there's no easy way (as in some other states) to do a citizen-led ballot initiative. I think it's hard under the circumstance to draw a straight line between a policy's popularity and its likelihood of being enacted. For example, Arizona probably has legal weed because it has ballot initiatives, not because it's more liberal than North Carolina.

The entirety of CLT is accessible by foot to Bojangle's. At ATL, you're probably getting on a train.

Survey says: CLT