Why Trump killed congestion pricing

New York’s plan has winners and losers — but this is an exercise in zero-sum politics.

I suppose I’ve always supported New York City’s congestion pricing in the abstract — it’s a policy that tends to appeal to us wonkish types. But I hadn’t thought about what a good deal it was from my standpoint until it went into effect in January after Governor Hochul reversed a previous postponement.

I live in Manhattan in the congestion pricing zone south of 60th Street. I’m pretty good about getting around town, and before the policy went into effect, I imagined the annoyance of an extra $0.75 or $1.50 added to each taxi or Uber trip. I chose the word “annoyance” because this initial instinct was somewhat irrational — I can easily afford the surcharge, even though it’s tacked onto several other preexisting fees.1

But then I started to notice the increasing number of trips — either within the congestion zone or returning back from the airport or a friend’s place in Brooklyn — where I was zipping along over bridges or down avenues at an unexpectedly fast clip. I probably take 25 taxi/rideshare trips per month, so the new charge means I’m out roughly an extra 30 bucks out of pocket. If each trip is now five minutes quicker, that saves me around two hours in traffic each month. I’m delighted to pay 30 bucks a month to get two hours of my time back, especially if the proceeds help to fund the MTA.

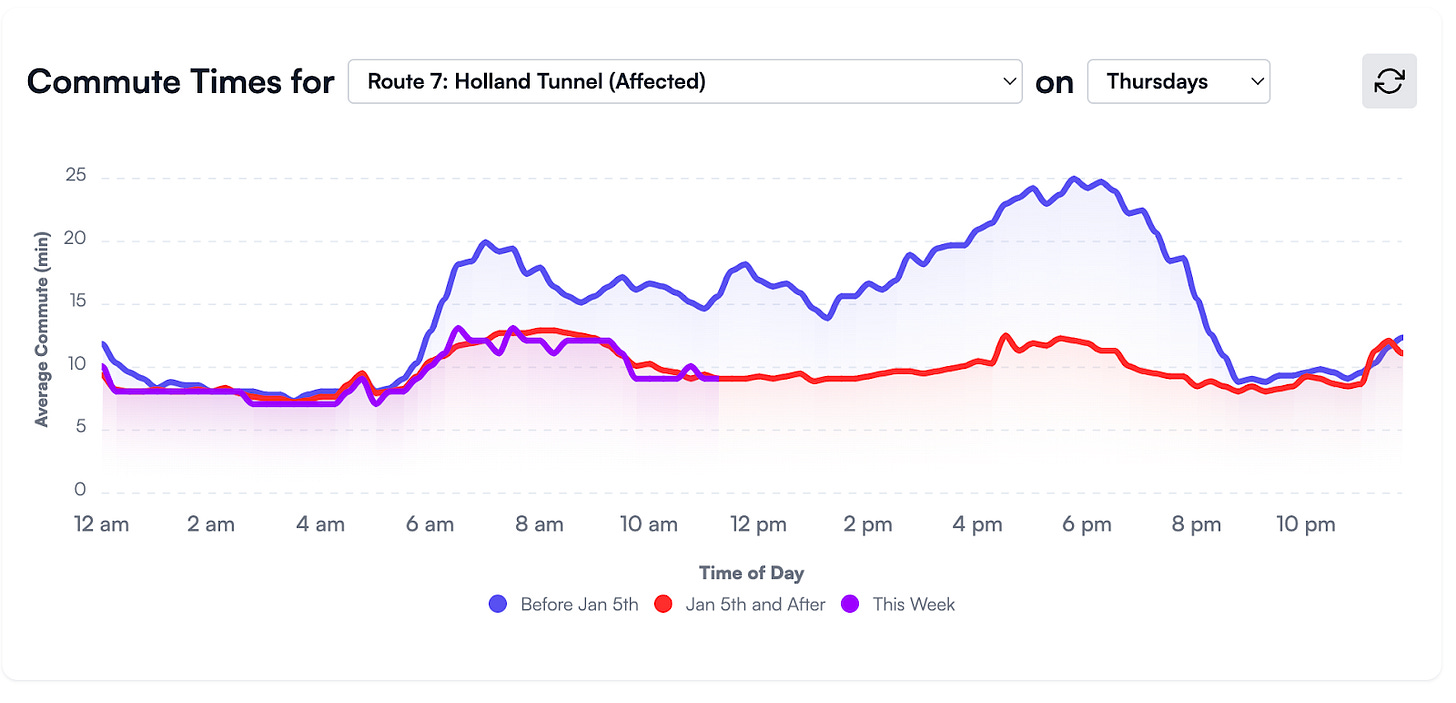

Then I began to hear from various friends and contacts — a lawyer in New Jersey, a poker player in Westchester County, a finance guy who lives in the Upper East Side but for some reason often takes FDR Drive to work to his job in FiDi — who are paying a lot more than that: the full $9 one-way toll2 for personal vehicles almost every weekday. They loved congestion pricing even more than I did, highlighting radically faster commutes. And the data backs them up. Commute times through the Holland Tunnel are now about 10 minutes faster during the morning rush hour and 15 minutes faster in the PM, for instance. I’m not sure what the lawyer is billing per hour, but I can guarantee it’s more than $9 per 25 minutes.

It’s important to note that all these people are pretty well-off, as I am. A $9 charge — on top of a $6.94 E-Z Pass toll for many of the bridges and tunnels connecting New York City with its suburbs3 — can become more prohibitive if you’re working for an hourly wage. Still, these commuters are not alone. In a Morning Consult poll earlier this month, congestion pricing was favored 66-32 by workers who commute into the congestion zone a few times a week and 51-46 by those who do so a few times per month — while being opposed 27-47 by New York voters statewide.

So when the White House announced yesterday that it would seek to kill congestion pricing — and then President Trump took a victory lap by sending out an image of him as the literal king of New York City — one might ask who the constituency is for this, exactly. (The victory lap is premature: congestion pricing remains in place while the courts sort out the mess.) Of course, Hochul has no credibility on the matter; her delay of the policy last June was partly because of concerns that it could hurt Democrats in Congressional races and she reinstated the policy only after the November election.

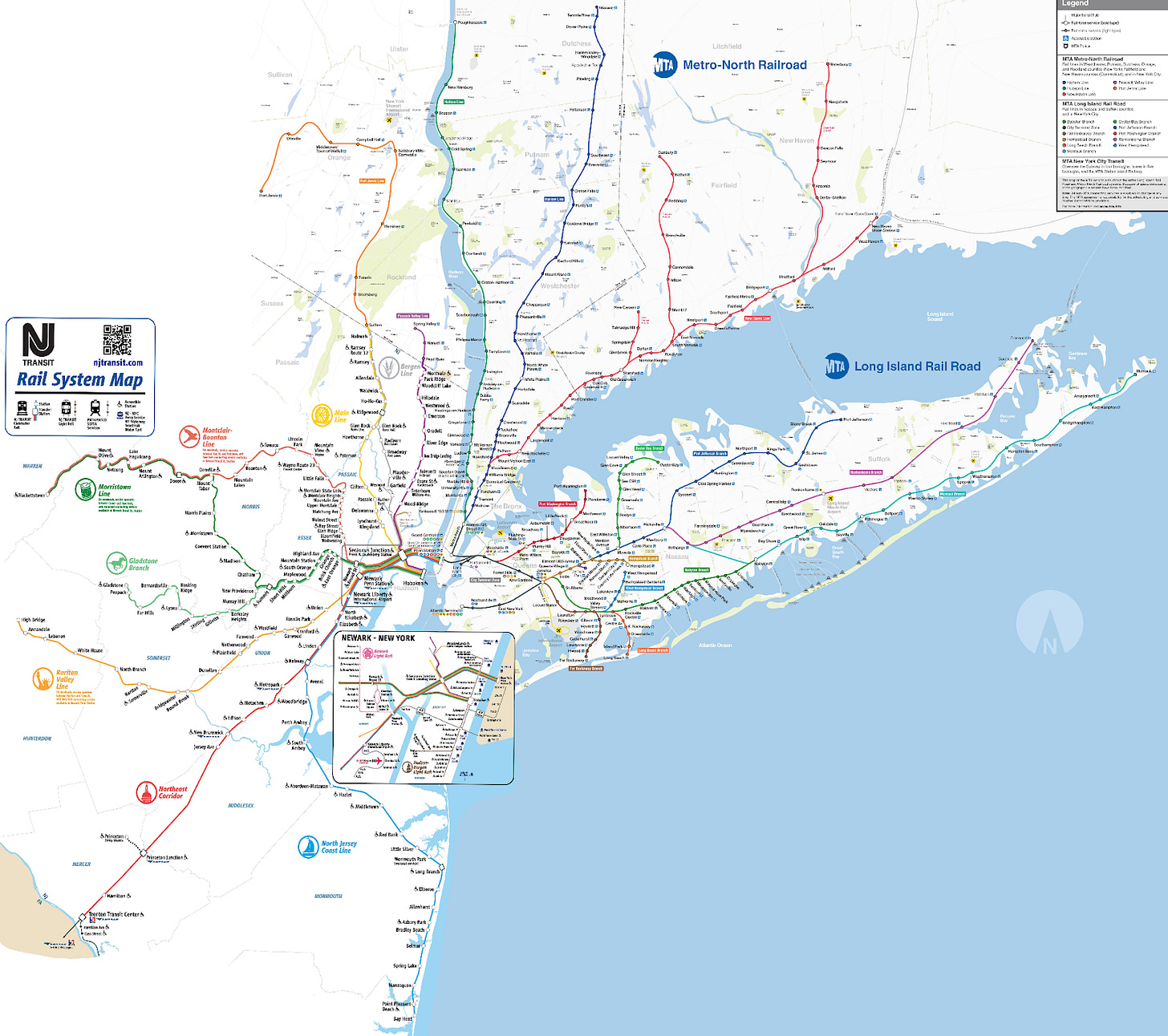

Although you might imagine throngs of middle-class commuters driving from New Jersey, Long Island, Westchester County, and Connecticut into the congestion zone, this isn’t actually that much of a thing here. Among people who work in Manhattan, 6.5 take public transit for every one who drives solo4, according to 2023 data from the American Community Survey. The subway isn’t the only option; the MTA’s Metro North and LIRR, along with NJ Transit and the PATH, provide relatively clean, frequent, comprehensive service. There are dead zones, like the west side of the Hudson River into New York State, but not many.

Moreover, although we Manhattanites like to think of ourselves as the center of the world, most workers in the metro region do not commute to Manhattan. Even excluding the growing number of people who work from home, only about a quarter of workers in New Jersey’s Hudson County, immediately across the Hudson River, commute to Manhattan, as do only one-fifth in Westchester County and less than a sixth in Nassau County on Long Island.

The winners and losers of congestion pricing

That’s not to say there are no losers from congestion pricing; every policy has trade-offs. Another regular in my poker game lives on 61st Street, exactly one block north of the congestion zone, so I can understand why he’s annoyed. And even if there aren’t many working-class commuters who regularly commute to Manhattan in their personal vehicles, with more than 20 million people in the Combined Statistical Area, there will be some; the Census Bureau’s data suggests they’re disproportionately likely to be older, which correlates with higher political engagement.

Let’s take that calculation I ran above: commuters through the Holland Tunnel are saving about 25 minutes per day round trip for a $9 additional toll one way. In principle, that’s a good deal if you value your time at $22 per hour or more, equal to $44,000 annually if working 40 hours a week over the course of the year.5

But the economics are more complicated than that. Overall, the failure to properly charge for externalities like traffic creates deadweight losses, meaning that the economy is less efficient — this is literally Econ 101. But there are relative winners and losers. Congestion pricing transfers welfare to people for whom the $9 charge is a good deal from people for whom it isn’t. And it shifts utility from outside the congestion zone to people within it. Traffic (and all those parking spaces) impose externalities on people within the commuting zone, including noise, pollution, and making our own travel times longer. Conversely, fewer people with New Jersey license plates means the roads are clearer when us Manhattanites are running late to a meeting or dinner.

The net effect on Manhattan-based businesses is hard to say. In one sense, making it more costly to enter Manhattan would seem to be bad for business. But there are several favorable trade-offs. Making it faster to travel within the commuting zone should encourage business from locals. Commuters who shift from driving to regional rail services like Metro North can still linger in the city to run errands or get dinner before catching their trains home (and now it’s less of a problem if they have a couple of glasses of wine.6) And if upper-income people are now more likely to drive to Manhattan for a Rangers game or night out on the town because there’s less traffic on the roads — even if lower-income people are less likely to do so — well, now you’re filtering for customers with more money to spend.

For people taking public transit to work, there’s a short-run cost — more crowded trains — and a long-term benefit (more money into the MTA). The NYC Subway is still running below its pre-pandemic capacities, though the numbers are rebounding. I take the Metro North’s Hudson Line fairly often, and there’s usually plenty of space, but I can’t speak to the other regional rail systems. In the long run, the theory would be to add more rail services if there’s more demand for them. What does get dealt out of the hand a bit is NJ Transit and PATH since they’re not part of the MTA. That may be part of why New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy, a Democrat, thanked Trump for his move.

But I don’t think that’s the whole answer. Let’s dig deeper into the commuting data.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Silver Bulletin to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.