Why the political clock is ticking for TikTok

Game theory and psychology support bipartisan action against the company.

It’s not often that I’m going to publish three days in a row, but sometimes there’s a lot of news that’s right in my wheelhouse. I’m going to be slightly dark for the next several days between travel and a review of copy edits for the book, but the goal is to publish one free and one paywalled post next week. To sign up, just click on the link below.

EDIT (March 11): Putting this back on top of the homepage to freshen things up as I’m indeed in the aforementioned book/travel crunch. Since initial publication, former President Trump has criticized the TikTok legislation. This was a flip-flop: Trump had signed an anti-TikTok executive order in 2020 which was later blocked by courts. However, Trump has subsequently backed off a bit. Betting markets think the legislation is still likely to pass the House. but are less certain about what happens from that point on. I think the original analysis holds up fairly well: as Trump’s waffling shows, it’s not so clear who the winners and losers of the legislation would be, and that makes bipartisan cooperation more likely.

Somewhat contrary to the conventional wisdom, politics is not a zero-sum game. Instead, it’s in the broad family of mixed-motive games where the various players have some interests in common and others that are opposed. Yes, there are a finite number of senators, governors, representatives and presidents. But current legislators also have some shared interests such as in protecting incumbents. And other things being equal, both Democratic and Republican members of Congress would like to promote the interests of the United States — particularly when they feel backed into a corner.

TikTok may be about to learn this lesson the hard way. On Thursday, the House Committee on Energy and Commerce voted 50-0 to advance a bill that would give “China's ByteDance six months to divest from short video app TikTok or face a U.S. ban,” according to Reuters. Under the bill, H.R. 7521, TikTok would qualify as a “foreign adversary controlled application”. China is one of four nations (along with Iran, Russia and North Korea) covered by the term “foreign adversary country’’ — but the bill isn’t even as subtle as that, mentioning TikTok and its parent ByteDance directly.

The White House has signaled its support for the bill, it has plenty of bipartisan and ideologically diverse cosponsors, and Republican House Majority Leader Steve Scalise has said he will bring the bill to the floor for a vote next week. It could get bogged down in the Senate, and will come under court challenges for its First Amendment implications. But it has a lot of momentum, and this post is an effort to explain why.

The committee vote came after TikTok sent a push notification to many of its users claiming that “Congress is planning a total ban of TikTok” and urging them to call Congress. This was probably a misstep by ByteDance. One problem is that many of the people who did call Congress were below legal voting age. It’s one thing to have your phone lines jammed by constituents, but another if its teenagers with a rabid TikTok habit.

A second problem is that TikTok’s claim was misleading — one of the bill’s Republican cosponsors even called it “communist China's dangerous propaganda” — since ByteDance would have 180 days to sell TikTok rather than face an immediate ban. If you’re a company that’s facing scrutiny for promoting misinformation, you probably want to be more precise in your high-profile public communications.

Third, there is the psychological factor. Giving rival factions a common enemy can often encourage them to set aside their differences.

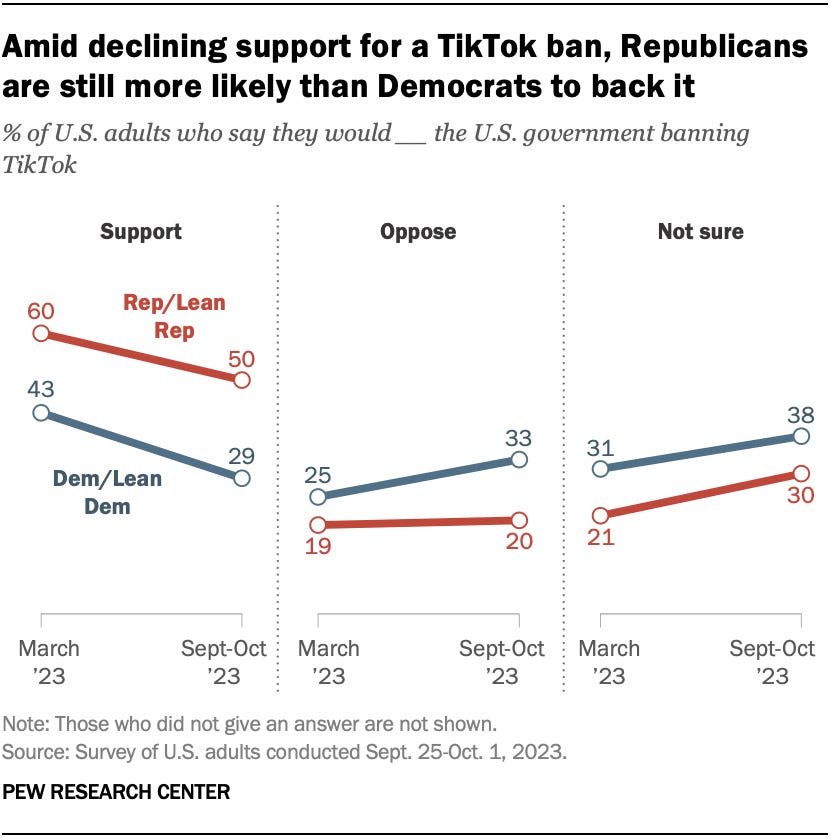

If the legislation had a clear political winner, that might nevertheless preclude this sort of bipartisan consensus. But the politics of H.R. 7521 are unclear. On the one hand, Republicans are generally more hawkish toward China. And Republican voters are more likely to support a TikTok ban in polls:

On the other hand, Democrats are generally more concerned about misinformation. And there are credible claims that ByteDance is putting its thumb on the scale in ways that favor Chinese interests and also generally make Joe Biden’s life harder — particularly over the conflict in Gaza, where pro-Palestine hashtags are disproportionately more likely to appear on the platform than pro-Israel ones:

TikTok’s users are young, and young people are comparatively more sympathetic to Palestine than older ones — but not by the roughly 80:1 ratio that you see in the hashtag distribution. I would not treat this data as dispositive — expression on social media can be contagious and overstate the degree of consensus. But this matches a pattern in other TikTok content that is sensitive to China, such as tags critiquing its policy toward Hong Kong.

Supporting the bill isn’t risk-free for Biden. Although supporters of a ban outnumber opponents in polls, the margins have been getting narrower, and it’s also plausible that TikTok users are more impassioned about the issue than those who would seek to crack down on it. Moreover, this comes at a time when Biden is losing support with young voters, who are more likely to think favorably of TikTok. Then again, older Americans are more reliable voters than younger ones. So if you’re going to err in one direction, it probably ought to be toward policies that older voters like.

It’s also unclear exactly what effects social media has on political behavior. Some research suggests a great deal, but regular readers of this newsletter will know that I’m wary of the category of “misinformation”. For instance, given the relatively small numbers — in advance of the 2016 election, Russian agents “published more than 131,000 messages on Twitter and uploaded over 1,000 videos to Google’s YouTube service”, tiny as compared to the overall volume of activity on these platforms — the notion that Russian propaganda decisively influenced the 2016 election is dubious. If nothing else, a TikTok ban would provide researchers with a natural experiment on the influence of particular social media platforms.

But the very fact that the political implications are ambiguous is precisely why the bill has bipartisan support. When there’s no clear winner, the non-zero-sum aspects of politics are more likely to prevail.

I hope this passes. China does use Tik Tok as a weapon. There is a reason the algos for users in China are different than for U. S. users. I think Tik Tok is one reason the youth are so messed up. (Note that I said ONE reason, NOT the reason or the like.)

At the same time, I'm nervous that someone will sneak some anti-free speech stuff into the bill.

Bytedance is basically a CCP cutout. TikTok is the world’s most successful spyware. Compare what our teens are pushed by the algorithms versus what Chinese teens see. In China, the feed is about kids doing well in classes, science contests, and wholesome material. American teens are fed a steady diet of detrimental content.