Why didn't anyone predict the American pope?

Prediction markets and the conventional wisdom have limitations when they become feedback loops.

I’d been studiously avoiding writing a post about the election of the new pope here at Silver Bulletin. For one thing, I don’t know anything about the Catholic Church. Maria and I covered the papal election in a recent Risky Business episode and I think it was a good segment, but mostly because we approached it at a deliberately high level of abstraction, mainly talking about the strategically interesting voting system employed by the College of Cardinals.1

But make no mistake: the election of Robert Francis Prevost — a 69-year-old Chicago-born and Villanova-educated man who yesterday became Pope Leo XIV — is a huge story, not just for global Catholicism but also for American politics.

For the first time in their lives, many non-Catholic Americans have a pope they might find highly relatable — Prevost is even a Chicago White Sox and college hoops fan. This particularly hits home if you know Chicago, where I lived from 1996 (when I began school at the University of Chicago) through 2009. A lot of the memes circulating yesterday were actually funny; I spent 20 minutes yesterday trying to come up with one about calling dibs on parking spaces but couldn’t land the joke.

And Prevost is an apparent swing voter who even seemingly has a Twitter account — I’m saying “seemingly” only out of an abundance of caution since it would be a hell of a long con to maintain an account like this since 2011 on the off-chance that he would one day become pope. On Twitter, Prevost occasionally expressed opinions about American politics, mostly through retweets. In particular, along with retweeting jokes about social distancing and sympathy for George Floyd, he recently linked to or retweeted several articles critical of Vice President JD Vance and the deportation of Kilmar Abrego Garcia.

Vance, a converted Catholic who had met with Pope Francis on Easter Sunday shortly before his death, was conspicuously tepid in his praise of Prevost, distancing himself by saying he was “sure [that] millions of American Catholics” would pray for Prevost but not suggesting that he would do so himself.

News outlets are slow to adjust to America’s changing relationship with the world under Trump

Axios did better than many news outlets by at least publishing an article earlier this week that covered the “buzz” Prevost was generating. However, they ultimately dismissed his candidacy by citing a scholar who said that the church wouldn’t want to give America any more influence:

Yes, but: A pope from the United States is unlikely for several reasons, including that an American pope would give the U.S. even more influence than it already has, Loyola University scholar Michael Canaris tells Axios.

With the benefit of hindsight, this logic seems to have the polarity of the situation reversed. The Catholic Church might not want the United States to have more influence. But it might want to have more influence on the United States, which it presumably will have now that there’s a pope who is fodder for Barstool Sports memes and whose every utterance will be scrutinized by the American media.

And while I don’t want to speculate on this too much, Prevost’s anti-Trump stances, though expressed with some subtlety, were at the very least not a disqualifier for the College of Cardinals. America’s relationship with the rest of the world has profoundly changed during Trump’s second term. If Trump completely upended the Canadian election, maybe he negatively polarized the College of Cardinals, too?

Prediction markets missed this one

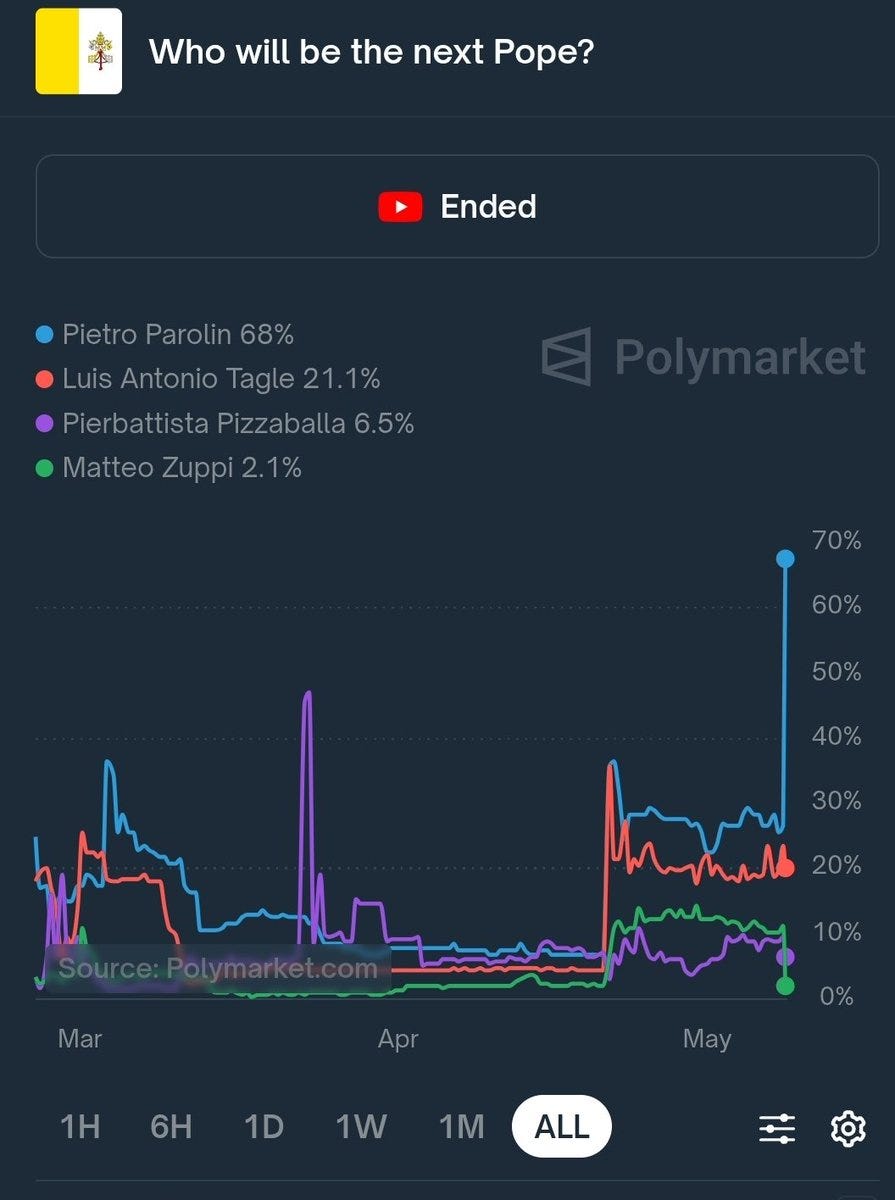

Of course, there can be more prurient reasons to be interested in the papal election, such as trying to make money at prediction markets. At Polymarket, which I consult for, around $30 million was bet on the identity of the next pope, and little of it on Prevost, whose implied probability of being elected hovered at between 1 and 2 percent. Some Catholics consider it immoral to bet on papal elections; as will come as little surprise, I don’t share that view. But even if you do, I’d suggest that this is an interesting sociological phenomenon on several levels.

One or two percent chances happen sometimes, particularly in situations where there are dozens of plausible choices. The College of Cardinals has 251 members2, and technically speaking, any baptized Catholic man is eligible to become pope. On long lists of candidates in mainstream news outlets, Prevost’s name was sometimes included (see e.g. Time, BBC, the New York Times) but sometimes not (Washington Post, The Ringer, USA Today) when if anything you’d think there was a bias toward speculating about the possibility of an American pope.

So Prevost’s low standing in prediction markets was probably a good summation of the conventional wisdom entering the conclave. I think there can be real value in that, creating greater accountability by forcing to people to put money where their mouth is and to quantify probabilities rather than being hopelessly vague.

It’s not that the markets had been particularly confident before, with the leading candidates — Pietro Parolin and Luis Antonio Tagle — having no better than roughly a 30 percent chance when the papal conclave began on Wednesday.3 But when white smoke came out of the Vatican yesterday on just the second day of the conclave, Parolin’s odds shot up, presumably on the assumption that the quick decision was good news for the frontrunners.

As you can hear in the podcast with Maria, I don’t think this assumption was inherently unreasonable. But that assumes you can identify the frontrunners correctly in the first place. This was the sort of situation where outsiders — and particularly the sorts of outsiders who might be inclined to bet on papal elections, whom I doubt have any more expertise in the Catholic Church than I do — were going off so little information that they probably ought to have hedged a lot more.

In my research after the fact, I did come across one news outlet that — while not predicting Prevost’s election — at least accurately captured this dynamic. It was a specialized one: the Catholic News Agency, which warned against overconfidence from the media and betting markets:

Tom Nash, a contributing apologist for Catholic Answers, told CNA that it’s clear who “the most well-known cardinals are heading into the conclave,” but that does not necessarily show “how they stack up as papabili in the eyes of their fellow cardinal electors.”

“I think some cardinals who are faring well among the oddsmakers and media, including because of the prominent role they had under Pope Francis, may actually have less of a chance than some others who are considered long shots,” he said.

Indeed, there’s some precedent for this sort of surprise. Pope Francis — then Jorge Mario Bergoglio — had also been considered a long shot when he was elected in 2013, initially having 55-to-1 odds against.

When do prediction markets provide relatively more and less reliable information? There’s not a super simple answer to that question, but here are some factors I’d consider:

How liquid is the market?

How sophisticated is the modal trader in having domain knowledge about the subject at hand?

Whether or not the average trader knows what he’s doing, is there a class of professional traders with the capital to correct any imbalances?

Is the situation easy to model through statistical techniques?

Is it a repeated event where traders have the opportunity to refine their estimates through trial and error?

And is there local knowledge — or even insider knowledge — that might contribute to the wisdom of crowds?

The single situation where prediction markets have routinely most impressed me is on election days when votes have begun to be counted and markets are trying to forecast the winners based on incomplete information. They are frequently much faster to hone on the correct winners than the mainstream media, which can be reluctant to “call” winners and risk having egg on their faces later. If you look at that checklist, you can understand why prediction markets perform so well in these circumstances:

Lots of money is bet on major elections, both explicitly through prediction markets and implicitly through stock market futures and other financial vehicles.

While I’m not sure the average trader is that sophisticated in election betting markets, and while there isn’t quite a professional class of traders in the same way that there is for, say, sporting events4, there’s enough money on the table to incentivize everyone from investment banks and hedge funds to skilled hobbyists to take the problem seriously.

Although building real-time election day forecasts is a very difficult problem, you’ll nevertheless do much better by working through a statistical model rather than by “winging it.”

Elections occur often enough that these estimates can be refined through empirical analysis. Was your model overconfident or underconfident in the past?

While I’m skeptical that either there’s that much inside information filtering into election betting markets and really even that such knowledge is all that useful anyway, traders can benefit from taking a fine-grained approach, such as by focusing on particular states or counties or scraping data from their websites.

In contrast, for a papal election, pretty much the opposite is true on every indicator. The choice of the pope presumably doesn’t have broader implications for financial markets, so well-capitalized institutional investors are unlikely to be involved. The modal trader probably knows little about the Catholic Church. Papal elections occur extremely rarely. And papal conclaves include relatively few participants, and they’re sequestered to prevent any leaks to the outside world.

In such situations, the conventional wisdom can just feed back on itself. Maybe it was reasonable a priori to think that Parolin or Tagle were more likely choices than Prevost, for instance. But these probably ought to have been pretty weak priors. Once the media begins to write about them as frontrunners, however, those perceptions can become entrenched. Everyone assumes that everyone else knows something, when in a case like this, they probably don’t.

And prediction markets potentially contribute to this process because of their seeming mathematical precision. That they can be extremely wise in some circumstances doesn’t mean that they will always be.

So both traders and the news outlets that cover prediction markets ought to zoom out a level. Is this plausibly a setting where enough items from that checklist are marked so that markets can hone in on accurate estimates? If so, it will often be wise to jump on the bandwagon and bet on the favorites. But if not, they can be prone toward overconfidence, and you might want to invest in the underdogs instead.

Which is very similar to the process used to select presidential nominees in the event of a brokered convention.

Although only about half of them — those under 80 — are eligible to vote in papal elections.

Personally, I had been partial to Pierbattista Pizzaballa just for his name.

Just because major elections around the world occur perhaps a couple of times per year, while sports happen every day.

As a Catholic who believes that betting on popes is the highest form of 'tempting fate', I wouldn't have bet on it. However, if I had known that there was a American under consideration... I would have giving him a 10% just because of the politics of American Catholicism right now.

Bluntly put, there's been a show down between the International Catholic organization, the American Bishops, and the American conservative Catholics, and the American liberal Catholics. And it's a 4 way show down right now, make no mistake.

For the church itself, reinforcing and bringing back into the fold the Liberal Catholics is a priority, given how that is the wing that has shrunk over the past two decades, and the international catholic organization is more and more ideologically in line with this branch of American Catholicism. But it's also the wing of 'lapsed Catholics', so it's the most finicky branch and then one that pushes hardest on the pain points for everyone.

The American Bishops are a lot more conservative on the whole than the international bishops, and they open their mouths and say things about immigration and the like that sound a awful lot like the gospel of prosperity or the Evangelicals church. This is and has been a huge pain point, but the international church hasn't put it's foot down hard because I believe there is fear of causing a split akin to the creation of the Anglican church by Henry the VIII. (FYI, this is why the Trump Pope picture played ESPECIALLY bad to Catholics. It's real easy to read that as "American Bishops, I could be your pope")

The conservative and liberal branches I feel I don't need to explain for the most part, as that part of the American experience is on full display 24/7, for better or worse. But the important part of this is a paradoxical issue of growth: Conservative Catholicism has been steady in it's participation, but it's not growing and it tries to make demands Catholicism as if it owns it, rather than serving the community. The Liberal branch gets the serving part and tend to be very chill towards the larger organization, but the liberals are flaky, lapsed, and tend towards complete disengagement.

In this environment, Pope Leo is the 'Secure America' pope.

1) His ties to Francis makes him a hit internationally, and his views are more of the same.

2) Being an American, he can make a pretty good neutral argument to both the conservative and liberal congregations.

3) As a American, he can also reach around the American Bishops, which lessens the risk of a Anglican style split and forces them (somewhat) to play ball with the rest of the world.

4) There is also a increase in church participation in a pope's country when they are elected, which means that the range and ideology of both an individual parish and the local leadership tends to widen as more people get involved.

With these details in mind the Church electing a American Pope makes sense,

but it's also a sign of how much concern they have for American Catholicism at the moment.

I live in Italy, and I can tell that here, in the last week, Prevost was considered among the 4-5 most probable. In the last two days he was considered the 2nd most likely. And, after the first day of ballota, some newpaper considered Prevost the favorite n.1. I did bet on Prevost (in a local website) one week ago. Probably there was some bias in the US.