There’s still time to submit questions for this month’s edition of Silver Bulletin Subscriber Questions. You can leave questions in the comments of last month’s post or the Subscriber Chat. We’ll probably make this a lightning-round edition or even a video edition where I don’t get caught up in my usual long-winded answers. This might run as soon as tomorrow, but more likely this weekend based on our other content plans.

Also, as I was working on this piece, Sean Trende at RealClearPolitics published an article on the same topic! If you’re interested in this subject, go read Sean’s excellent article too!

On Monday afternoon, I voted. I hadn’t really been planning on it — I mean, I’d been planning to vote, but not on Monday. New York only implemented early voting a few years ago, and I voted early in 2020, but it was at a voting center in Madison Square Garden set up as part of a special COVID program rather than my usual precinct. I suppose I knew that early voting was now a Permanent Thing in New York, but it wasn’t part of my routine. But there was no line when I was walking past my precinct to get coffee, and I was in and out in 5 minutes. Now that I know, I’ll vote early every time. (Election Days can get busy around here.)

Sure, not the most exciting story. But it goes to show you a couple of things. The rules for early voting are constantly changing, some states made one-off provisions for COVID, and different types of voters may have different levels of awareness about their options.

So when people ask me how early voting is incorporated into the model, the answer is that (with one extremely minor exception1) it isn’t — even with a lot of effort, I’m doubtful that there would be a good way for it to add much value. Here are the reasons why:

There aren’t good baselines, especially coming off a COVID election

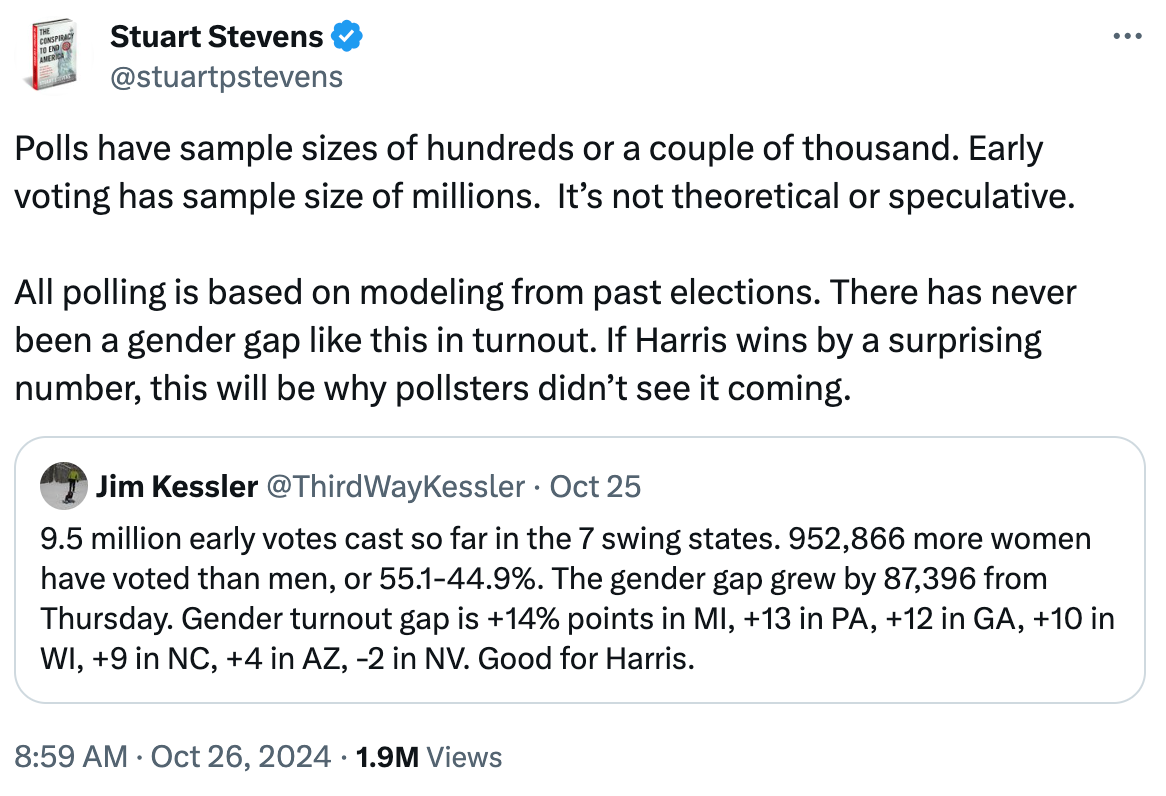

Are you familiar with the infamous Literary Digest poll of 1936? I suspect Stuart Stevens isn’t, given that the former Mitt Romney advisor tweeted this the other day:

Indeed, more than 57 million people have already voted, orders of magnitude more people than in a typical poll. So how can it not be more informative than polls?

Well, Stuart Stevens, the answer is that early voters — even if we know how they voted, and we don’t — aren’t a representative sample of the electorate, while a poll is at least theoretically supposed to be. In 2016 — the last non-COVID election — Michael McDonald was able to track down a partisan breakdown of early voting data in 13 states. Some of it is pretty wild stuff. Democrats led the early vote in West Virginia by 12 points, but Donald Trump eventually won the state by more than 40. More Republicans than Democrats voted early in Colorado — but Hillary Clinton won there. Similar states can produce surprisingly different patterns. Florida and North Carolina were then both swing states, but the early vote was blue in North Carolina but purple in Florida, where Republicans have traditionally emphasized early voting to their older voters.

On average, the D less R margin in the early vote mispredicted the final Clinton/Trump margin by 14 points! Pollsters get yelled at when their polls are off by even 3 points, and anything more than that is considered an absolute disaster. Imagine if a poll was off by 14 points: no one would ever listen to it again! And yet we get the same frankly amateurish analysis of the early vote in every election.

That brings us back to the Literary Digest poll. In 1936, the magazine surveyed almost 2.3 million voters, a colossal number. They had Alf Landon, the Republican, beating Franklin Roosevelt 57-43, an epic landslide. The election was a landslide — but for Roosevelt, who won by 24 points, including all but two states.

Just a mere 38-point polling error. What happened?