I've tracked my last 800 flights. Here's when you really need to get to the airport.

The 2-hour rule is usually a myth.

Dec. 24, 2025: Amidst the holiday travel season, we’ve updated this article with some additional charts. But the spreadsheet version at the end still reflects our most comprehensive approach. The text of the article is unchanged from August.

My overriding philosophy for this newsletter is to write about what I know about. And I know a lot about air travel. Over the past 15 years, I’ve taken something like 800 flights.1 That tally includes literally everything from the middle seat of the bathroom-adjacent back row on Spirit Airlines to first class on Emirates (I lucked into a free upgrade).

So as we’re approaching the peak of summer travel season, it’s time to put this out there: U.S. air travel gets a bad rap. Many American airports are much more pleasant than they were even a few years ago. And security lines are often faster — as of last month, you don’t even have to take your shoes off anymore. We can all remember our worst experiences, and I’ve had a few, from having to double back because I left my wallet at my hotel in Raleigh to not realizing that my connection in Sao Paulo was at a different airport. But the default experience is trending toward efficiency.

Guidance on when to arrive at the airport has been slow to catch up, however. At View From The Wing, Gary Leff recently estimated that $83 billion worth of productive time last year was wasted because of people showing up hours in advance at American airports.

Although I agree with the spirit of Leff’s critique, I don’t quite agree with his calculations. For one thing, excess time at the airport isn’t exactly wasted. Some airports can be pleasant spots for people watching, putting headphones on and getting some work done, or having a refreshing pre-flight beverage.2

But also, although many authorities recommend arriving as early as 2 or 2½ hours in advance even for domestic flights, you really don’t need to do that. Not unless you’re facing a multiplicity of adverse circumstances. As in some other areas, the experts are irrationally risk-averse.

True, most people don’t follow TSA guidance to a T, but many travelers are nittier about air travel than they need to be. An (unscientific) poll on X by the economist Bryan Caplan found that more than a quarter of his respondents arrive at the airport at least 100 minutes ahead of time as a default.

I often cut things closer. And while I like to gamble, my track record with flights is pretty good. Out of those ~800 departures, I’ve missed three or four due to being late, a rate of about 0.5 percent. That isn’t zero, but I generally agree with the phrase "if you never miss the plane, you're spending too much time in airports." Missing a flight is not an existential crisis. If there’s another flight on the same route in an hour, it may hardly matter at all, in fact.

Still, the biggest problem with that two-hour rule is that it’s one-size-fits-all. There are circumstances where you’ll really want to budget that much time, or even more, but others when you can pull up to the gate 45 minutes before departure and be just fine. So here are my detailed heuristics, honed from decades of experience. (Maybe all that time at airports wasn’t wasted after all.) For paid subscribers, I’ll even include a spreadsheet so that you can roll your own numbers.

The base case

My default is to allocate 60 minutes — one hour, not two — from walking through the airport doors until departure time. There are several important assumptions behind this, however, which usually fit my circumstances but might not match yours:

I’m flying within the United States.

I have some form of expedited security: CLEAR, TSA PreCheck or the priority lane.

I’m not checking bags.

And there are some reasonable backups if I miss the flight, as is almost always the case since I mostly fly from New York to other major cities and have decent status on some of the big carriers.

This won’t give you much time to hang out — but it’s enough of a buffer that you’re very unlikely to miss your flight. There are more things that can add time to the baseline than subtract from it, however — so let’s consider those complications.

The commute

Of the flights that I missed, none were really because I didn’t budget enough at the airport. Rather, all but one3 was because I misgauged my commute.

As we all know, the estimated travel times that Uber or Lyft shows you are often optimistic. You’re rarely going to be put in too much of a pickle in, say, Pittsburgh. But New York or Los Angeles is a different story. So as a default, I’d round up that commute time by 30 percent if there’s a reasonable likelihood of encountering traffic. For a purported 30-minute commute, for instance, I’d budget 40 minutes instead. (The spreadsheet allows for a more detailed set of calculations.) One other tip: at most airports, the PM rush hour is usually worse than the AM. That’s because they’re usually located on the outskirts of town, so you’ll be competing with commuters returning home to the suburbs from work.

And don’t forget to budget time to park or return a rental car if you need to: I’d add 15 to 30 minutes, depending on the circumstances, like that the LAX rental car facility might as well be located in San Diego.

The basics once you arrive

How big and busy is the airport? My 60-minutes-before-arrival default is calibrated to a midsize airport like Chicago Midway or either of the Portlands. I’d add up to 15 minutes for the very busiest airports like JFK, DFW or O’Hare. There are just more things that can go wrong — and also at airports like JFK, it can physically take a long time to walk to the gate. (The spreadsheet version lets you choose from about 60 American airports; estimates of added time are based on a combination of my experience and guesstimates from OpenAI DeepResearch.)

At big airports, you can round these times back down by 5 to 10 minutes if you’re a frequent flier or know the airport well.4 And pretty much any traveler can shave off at least 5 minutes for small regional airports like Santa Barbara where you’re already basically right at the gate the moment you pull up; this is almost impossible to screw up.

My baseline also assumes that you’re able-bodied. The spreadsheet lets you choose an option if you or someone in your party is slow-moving — say you have an 8-year-old with you or an 80-year-old — although you’ll know more about those circumstances than I do.

One subtle factor that I nearly got burned on recently: I’d add a buffer of 5 to 10 minutes if you have a connection to make. This might seem silly since it doesn’t affect the departure time at the originating airport. But it raises the stakes for missing your flight. Also, if you arrive at the very last moment, you’ll likely be asked to gate-check your bag, which can get you off to a slower start when making that tight connection.

International travel

The conventional wisdom is that you should arrive an hour earlier for international flights, and I don’t think that’s a bad heuristic. But this is a trickier question than you might assume. Most American airports don’t even have dedicated international terminals: some of the joy of airports is that the flight to Auckland could be right across the corridor from the one to Oakland.

The process of transiting from the airport doors to the gates is often superficially the same whether traveling domestically or abroad. In the U.S., you usually don’t have to clear customs and passport control before an international flight. The exception is places that are subject to the CBP’s Preclearance program, namely most destinations in Canada, the Caribbean, Ireland and the UAE. Preclearance is mostly a positive — it will save you time upon arrival — but you do need to budget for it when considering when to leave for the airport.

So let’s decompose this. What are the reasons you might want to arrive earlier for an international flight?

Planes are usually bigger and boarding starts sooner, and is often a shitshow because you’re sharing the gate with families and people speaking a million different languages.

You’ll often have to visit the check-in counter to verify your documents and get a boarding pass — and if not, they’ll check your passport at the gate.

Many international routes are flown at most a couple of times a day, so missing your flight is a huge inconvenience.

To break it down more precisely:

As a default, even if you think you’re fully checked in, I’d add 20 to 40 minutes to your domestic flight baseline for international travel, depending on your general experience level with flying abroad.

If you do need to visit the check-in counter, I’d add a further 15 minutes for business class and 30 minutes for coach.

And if you need to clear immigration before you take off — remember, this is not true for most destinations, but the most common exception is Canada — I’d add another 30 minutes.

If missing the flight would cause a huge inconvenience — your best friend annoyingly decided to hold a destination wedding in Buenos Aires, you’re the best man and it’s last flight of the day — you might add more time still. But this sort of situation can also apply for domestic flights, so we’ll cover these cases later.

Security and check-in

This is not an advertorial for TSA Pre or CLEAR, but I think if you do the math, you’ll find that they’re very much worth it if you value your time and fly with any frequency. It’s not just that they reduce the average wait time — they also reduce variance, and variance is at least half the battle when timing airport arrivals. Some degree of redundancy can even help: recently I’ve found that the priority line is often faster than the CLEAR line.

If I’m going through regular plain-vanilla security instead, I’ll add an additional 20 minutes to my baseline. As of 2018, all but a small handful of airports were faster than this on average, and TSA wait times have steadily improved for the past decade or two. In the spreadsheet, I do recommend adding an extra 5 minutes for the airports that have historically had the slowest security (BWI, EWR, IAH, JFK, LAS and MIA) and subtracting 5 minutes for very small airports, but this is a moving target as security protocols and staffing levels often change. Keep in mind that I already have you budgeting a little extra time at the busiest airports on top of this.

The circumstances when you’re likely to encounter really long lines are fairly predictable: holidays like Thanksgiving when a lot of families are traveling — they’re much slower than business commuters — or during bad weather when everything at the airport gets backed up. I’d add an additional 30 minutes for regular security or 15 minutes for expedited security during holiday peaks5 and the same amount for severe winter weather — these are additive, particularly given that the holidays often coincide with bad weather in most of the United States. Summer thunderstorms are less bad, since they can roll through quickly rather than delaying operations for days on end, but I’d add 20 minutes (for coach; 10 for priority security) during severe storms.

Budgeting extra time during bad weather might seem superfluous, since your flight will often be delayed, too.6 But when there’s a risk of severe delays or cancellations, it’s generally worth it to be on the ground so you can find alternative options. If you do miss your flight, it might take days before there’s another seat available.’

I never check bags unless I absolutely have to, since that slows you down on both ends of the connection. But if you do, budgeting more time is non-negotiable and indeed most airlines have a strictly-enforced 45-minute cutoff point for checking luggage. I’d add 20 minutes for this, rounding down to 15 minutes on a business-class ticket.

Beyond checking bags, there’s rarely a need to visit the customer service counter for a domestic flight, but these desks are often understaffed and full of customers troubleshooting edge-case issues, so I’d add extra time for that too. Lastly, I’d add 5 to 10 minutes, depending on your comfort level, if something in your check-in baggage routinely triggers the machines; TSA sometimes gives me a hard time when I’m bringing my fancy podcast mic along, for instance.

Cost-benefit assessment

I haven’t gotten to the most important part yet, the part that’s often neglected in debates about optimal airport strategy. What are the consequences of missing your flight?

I already covered the example when there’s exactly one flight left to catch to make it on time for your best friend’s wedding. There, you should be extremely risk-averse. The opposite case is what I encountered on my last trip to Chicago; my conference didn’t begin until 10 the next morning, but I flew out in the mid-afternoon the previous day to get dinner with an old friend. This circumstance allows for a more aggressive strategy, if you wish. There are something like 70 flights per weekday from New York to Chicago. My friend would have forgiven me if we had to push back dinner, and I could even have flown out the next morning and still made my event.

Really, though, there are two slightly distinct components of this question that interact with one another:

How many viable alternative flights are there if you miss your original one?

And just how bad are the consequences if you’re substantially late?

These have a multiplicative effect. If you have truly essential travel and there’s exactly one flight that will get you there on time, I’d add a full extra hour (60 minutes) on top of all the other buffers you’ve created. This really should be enough; for international flights, many airlines don’t even open their check-in counters until three hours before departure.

Just having one or the other circumstance isn’t so bad, however.7 The spreadsheet will let you work through various in-between combinations. Keep in mind that all of these are subjective estimates so you’re welcome to use your own. But if you’re cutting it at all close, it’s always helpful to know how many other flights are on that route later in the day.8

The last question: be honest, how much do you like hanging out at the airport? There’s no shame in saying “a lot”. Airports can offer an excuse to eat fast food9 or to drink at a weirdly-branded bar with strangers. In the spreadsheet, I add 20 minutes if you say you love airports — enough time for a quick bite or a beer — and subtract 5 minutes if you totally hate them. As airport amenities have improved, particularly with the redevelopment of the NYC-area airports, I’m finding I increasingly click on the +20 minutes option to give myself more breathing room.

One last thing to consider. The worst-case scenario is if everything goes wrong: there’s traffic and a long line at security and your flight as at the very last gate at the rump end of JFK Terminal 4. But statistically speaking, this is unlikely10, and the spreadsheet gives you an option to round down your buffer if there’s an opportunity to make up for lost time.

The spreadsheet

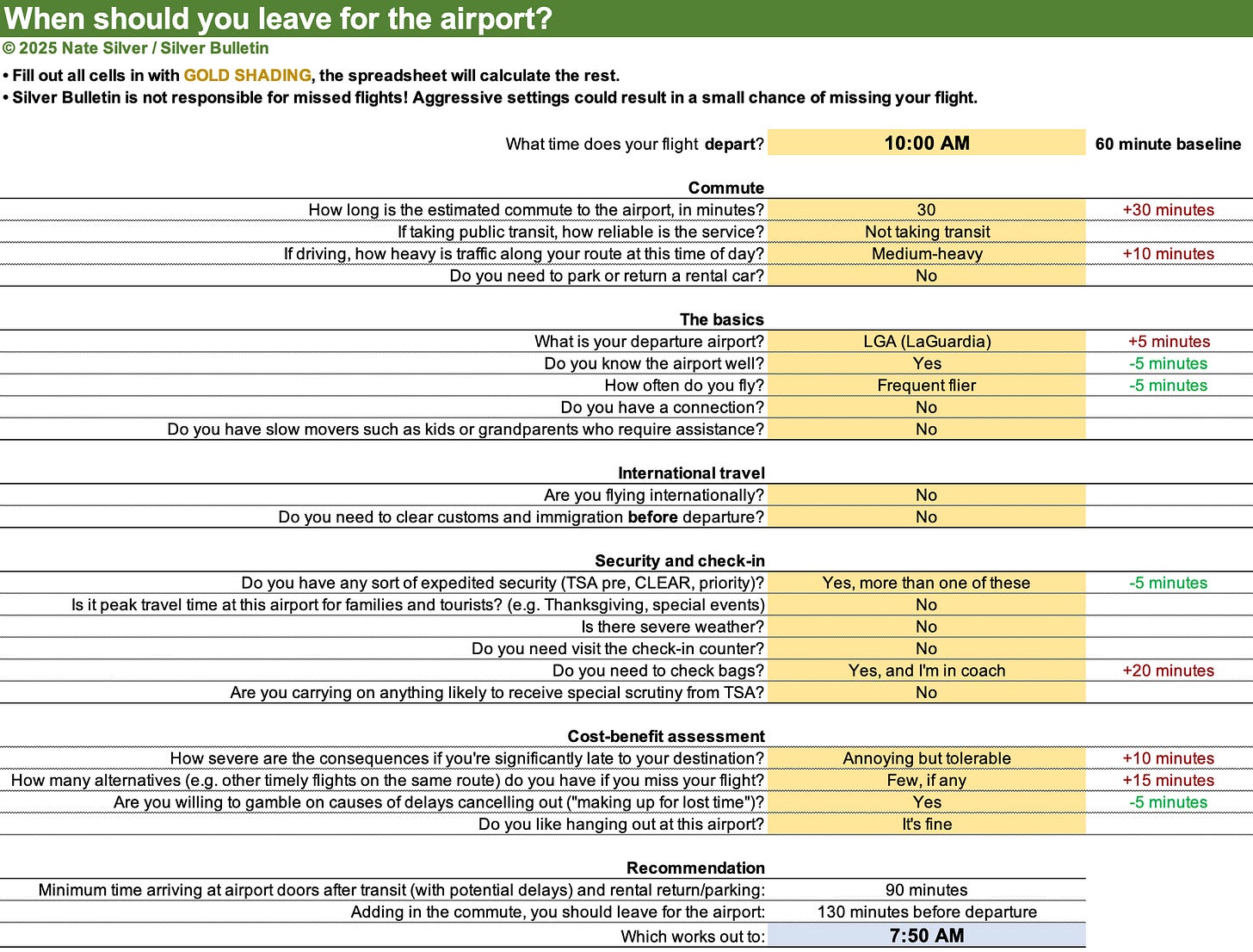

Here’s an example of how all this math adds up. Let’s say you’re flying from LaGuardia to Bangor, Maine, as I will be later this month. This is a fairly low-stakes trip, but let’s say there are some downside factors: there aren’t a lot of flights on this route, traffic can always be an issue in New York11, and your traveling companion is one of those incorrigible people who insists on checking luggage. The spreadsheet suggests that you should leave home at 7:50 a.m. for your 10 a.m. departure, budgeting 40 minutes for the commute (including a buffer for traffic) and leaving yourself 90 minutes at the airport.

It’s perhaps not the prettiest-looking spreadsheet — we’re going with function over form — but I’ve played around with it a lot, and I think it spits out reasonable estimates to accommodate a wide variety of circumstances. It does not guarantee that you’ll never miss a flight; how much risk you want to run is determined by the settings you choose under the cost-benefit section.12 But the point is, you ought to know a lot more about your circumstances than the TSA does. Here’s wishing you a safe and efficient journey the next time you fly.