Free speech is in trouble

Young liberals are abandoning it — and other groups are too comfortable with tit-for-tat hypocrisy

“What Harvard students think” is a topic that invariably receives too much attention. But I don’t think that’s true for evaluating opinion among young people or college students in general — who, after all, will make up the next generation of journalists, business leaders, politicians and pretty much every other white-collar profession. And after seeing the latest polling on what college students think about free speech, I don’t concern over “cancel culture” or the erosion of free speech norms is just some moral panic. In fact, I think people are neglecting how quick and broad the shifts have been, especially on the left.

College Pulse and FIRE — the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a pro-free speech advocacy group — recently published the latest edition of their annual survey. Although I don’t love using data from political groups — even ones I generally agree with — the good in this survey outweighs the bad. The methodology is detailed and transparent. And in surveying more than 55,000 undergraduates, the poll provides a look at student opinion across all sorts of colleges and universities — not just from the loudest or most privileged students at elite institutions.

Although I’ve seen a lot of media coverage about the FIRE survey, I’d never really dug into the details. I’m not sure exactly what I was expecting to see. But given my own political philosophy, I can tell you what I was hoping for: robust student support for free speech — perhaps in contrast to the often lukewarm support it receives among university administrators. Unfortunately, that’s not what the survey found. Here’s what it says instead:

College students aren’t very enthusiastic about free speech. In particular, that’s true for liberal or left-wing students, who are at best inconsistent in their support of free speech and have very little tolerance for controversial speech they disagree with.

Moreover, this attitude is broad-based — not just at elite schools. I was frankly surprised at how tepid student support was. A significant minority of students don’t even have much tolerance for controversial speech on positions they presumably agree with. There are partial exceptions at some schools — including my alma mater, the University of Chicago — suggesting the attitudes of professors and administrators play some role in trickling down to students. But this looks like a major generational shift from when college campuses were hotbeds of advocacy for free speech, particularly on the left.

Students have low tolerance for even mildly controversial speakers

The College Pulse/FIRE survey asks a long battery of questions, but many of them are focused on student perceptions about university administrators and not what they think about free speech themselves. Other questions ask about efforts to disrupt controversial speech — for instance, by shouting down a speaker. In these cases, there can be competing interpretations of what constitutes free speech — i.e. the students might say they are exercising free speech by disrupting the speaker — so these aren’t straightforward to interpret.

However, another set of questions directly asks students about their tolerance for controversial speech with no competing speech interest — specifically, whether a student group should be allowed to invite a speaker on campus. The exact wording of these questions is this:

Student groups often invite speakers to campus to express their views on a range of topics. Regardless of your own views of the topic, should your school ALLOW or NOT ALLOW a speaker on campus who previously expressed the following idea: ______________

Then, the survey presents students with a set of six examples — three pertaining to controversial ideas held by conservative speakers, and three about controversial ideas from liberal speakers. The order in which the students are presented with the examples is randomized in the survey — but here I’ll list them here with the conservative ideas first (which I’ve labeled as C1, C2 and C3) and the liberal ones (L1, L2, L3) second.

C1. Transgender people have a mental disorder.

C2. Abortion should be completely illegal.

C3. Black Lives Matter is a hate group.

L1. The Second Amendment should be repealed so that guns can be confiscated.

L2. Religious liberty is used as an excuse to discriminate against gays and lesbians.

L3. Structural racism maintains inequality by protecting White privilege.

Let me pause for an annoying little disclaimer. In today’s newsletter, I’m going to use the term “liberal” as synonymous with “progressive” or “left-wing”, even though I generally try to avoid that. Indeed, free speech is a bedrock principle of liberalism as classically defined. But since the FIRE survey uses “liberal” as a stand-in for left1, I’m going to do so as well.

OK, with that throat-clearing out of the way, let me show you the numbers, broken down by students’ self-described political orientation. The figures in the table reflect the percentage of students who would allow the speaker.

If you want to critique the examples FIRE chose, I’m sympathetic up to a point — the conservative statements seem slightly spicier than the liberal ones, although maybe that reflects my personal biases. I figured that the students would have a strong dislike for speakers C1 (“transgender people have a mental disorder”) or C3 (“Black Lives Matter is a hate group”) because they could be seen as promoting hate speech or misinformation. I don’t personally think “hate speech” and “misinformation” are terribly coherent categories, but leave that aside for now. This is a survey of college students, including some as young as 18. So I was just hoping to find general, directional support for free speech — even if not necessarily in every instance from first principles.

But I was much more surprised by responses to speaker C2 (“abortion should be completely illegal”). People obviously have strong feelings about abortion, and a complete abortion ban is unpopular. Still, this is a commonly-articulated, garden-variety unpopular political opinion that doesn’t make any sort of factual claim and can’t reasonably be construed as hateful. You’d think even students with a tentative, half-baked belief in free speech principles would tolerate it. And yet, 57 percent of students — including 68 percent of liberals — thought a speaker expressing this anti-abortion viewpoint shouldn’t be allowed on campus. That number kind of shocked me.

For that matter, tolerance for some of the liberal viewpoints isn’t all that high either. Only 57 precent of students think L2 — the speaker who says religious liberty is used as an excuse to discriminate against gays and lesbians — should be allowed, even though that sort of claim has been common in American political discourse for decades now

Still, to be clear, there’s a big gap between the liberal students and the conservative students. The conservatives are actually quite consistent, with roughly 60 percent support for both liberal and conservative speakers. The liberal students have a relatively high tolerance for liberal speakers, but little tolerance for conservative ones.

This isn’t just a Harvard problem

Harvard and other elite schools often rate poorly in FIRE’s overall free speech rankings — Harvard is dead last in the latest edition, in fact. But the survey data I’ve been describing is just one component of those rankings. When it comes to controversial speakers, students at non-elite colleges are just as intolerant as their Ivy League counterparts. Here are the average numbers across various college typologies:

You can look at this data in a couple of different ways. On the one hand, the Ivy League schools are slightly more tolerant of controversial speakers overall. On the other hand, they have a particularly wide gap between tolerance for liberal speakers and conservative ones. Students at elite small colleges — the so-called Little Ivy group — have an even bigger gap and stand out as being particularly inconsistent. Still, the numbers don’t differ that much from one type of institution to the next. As I’ve said, student support for controversial speech is low across the board.

What about at individual universities? I don’t want to make too much of these rankings because there are potential sample size issues — the survey polled a couple hundred students per school on average. So let me just list the top 5 and bottom 5 schools, which differ from the average enough to be comfortably outside the margin of error.

Hillsdale College, an expressly conservative university, unsurprisingly has off-the-charts tolerance for conservative speakers. To their credit, though, students there also have above-average tolerance for liberal speakers. Meanwhile, the University of Chicago, which has a long history of support for free speech — reiterated in 2014 in the form of something called the Chicago Principles — ranks third. Washington and Lee University, which adopted the Chicago Principles, ranks second.

Why did the campus left turn against free speech?

Rather than provide a comprehensive analysis of the reasons for this shift — perhaps we can go into more detail in future editions of this newsletter — let me just inventory a few hypotheses. By no means are these mutually exclusive — I suspect they all play a role.

Reason #1: Woke ideas are popular on campus and are considerably less tolerant of free speech than traditional liberalism

I’m at the point where I’m tired of putting the term “woke” in scare quotes. Although the word is sometimes abused by conservative politicians, there exists a distinctive and influential set of ideological commitments that differ from traditional liberalism or leftism. And wokeness — or whatever you want to call it — particularly differs from liberalism when it comes fo free speech, as James O’Malley writes:

The ideological shift that has surprised me the most is witnessing “free speech” become coded as a right-wing value, and something that when the phrase is uttered makes people sympathetic to “woke” ideas suspicious.

The argument is that unrestricted speech harms people. There isn’t an equal platform to speak in the first place, so racists and other unpleasant people are able to use the norm of free speech to terrorise groups who are oppressed.

I think the strangest example of this new norm in action was the response to Elon Musk buying Twitter. Traditionally, liberal ideology is fearful of overreach by powerful figures like billionaires, and is in favour of more permissive speech rules and norms as a hedge against their power. But the “woke” complaint about the new owner is that under Musk’s leadership, Twitter will not be censorious enough, and will be too permissive over what speech is allowed on the platform.

Reason #2: Normie Democrats are turning against free speech because of concerns over misinformation

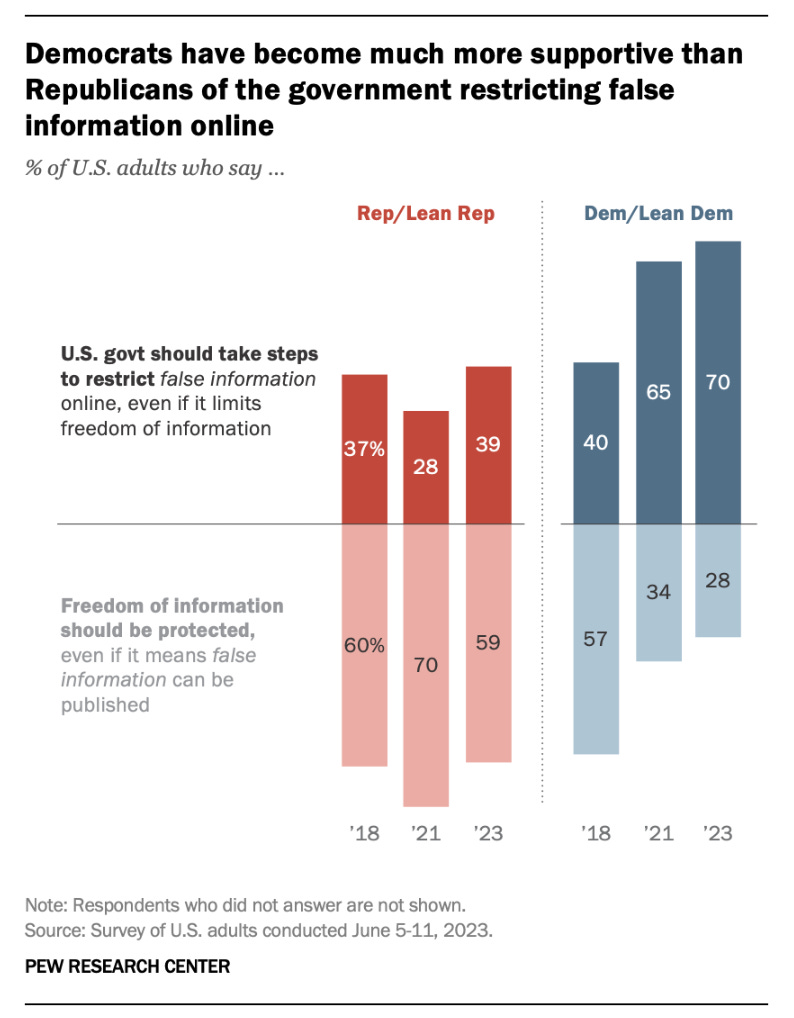

However, wokeism isn’t the only left-of-center movement that has raised concerns about free speech. Rank-and-file Democrats have shifted on the question too and now strongly prioritize restricting false information over protecting freedom of information:

Note that this shift is fairly recent — it came between 2018 and 2021, so it can’t just be attributed to the election of Donald Trump. (Maybe it had something to do with COVID?) And it’s a big shift — Democrats went from 57/40 in favor of free speech over misinformation in 2018 to 28/70 against it in 2023. A change that large will inevitably trickle down into universities with their mostly liberal students, professors and parents.

Reason #3: The younger generation is risk-averse in general

Teens and young adults in the U.S. increasingly defy the stereotype of younger people taking more risks. Instead, they show increasing rates of depression and neuroticism, and decreasing rates of risky behavior such as drug use and sex. This is particularly true among young people who identify as liberal. If you think controversial speech can cause harm — from psychological trauma to actual, literal violence — you might conclude that it’s not worth the risk.

Reason #4: The United States may be reverting to the mean

The U.S. has historically been an outlier in public support for free speech, and our laws are more protective of it than in many other Western democracies. Britain, for example, has significant curbs on speech, as does Germany. If America is becoming less distinct from the rest of the world — not something I regard as a hard-and-fast fact but a plausible theory, especially in the multicultural environment of universities — we might expect support for free speech to decline.

Reason #5: The adults in the room are often hypocrites

I don’t think it’s always true that people are hypocritical about free speech. Some partisans literally can’t seem to understand that some of us at least strive for a more high-minded, principled approach, even if we don’t always live up to it. Thinking that everyone else is a hypocrite is a convenient belief to hold if you yourself are a hypocrite.

But is there a lot of hypocrisy around free speech? Of course there is. Republicans who rail against wokeness put significant limits of their own on academic freedom. Supposed “free speech absolutist” Elon Musk has often taken a censorious approach toward content he doesn’t like while tolerating censorship by foreign governments.

While I’ve somehow made it this far without using the words “Israel” or “Palestine”, recent international events have uncovered instances of hypocrisy too. I have no interest in refereeing every incident, but cases like this — in which editor-in-chief Michael Eisen was fired from the life sciences journal eLife for retweeting an Onion article that expressed sympathy with Palestinians — fall under any definition of “cancel culture”.

Meanwhile, major donors are reconsidering their contributions to universities whose administrations they say weren’t sufficiently critical of Hamas and the October 7 terrorist attacks. Personally, I think donating to an already-rich, elite private university is one of the least effective possible ways to spend your money, so I’m happy whenever donors find an excuse to pull back. But leaving that aside, I don’t think these donors have really thought through their strategy.

True, a lot of university presidents have expressed a conveniently-timed, newfound commitment to free expression that didn’t match their previous behavior. Still, if I were one of those donors, I’d say “great, and now we’re going to hold you to it. The next time you stray from your commitment to free speech — particularly when it comes to students or faculty who express conservative or centrist viewpoints — we’re going nuclear, permanently ending all contributions to the university and telling all our rich friends to do the same.”

And although I’m not sure I have any business talking to college students — although I have delivered a number of guest lectures and commencement addresses — if I were, I’d use this as a teaching moment, telling students that now that they’ve found out what it’s like to stand up for a controversial, unpopular position, I’d hope they’d be more respectful of the rights of others to do the same.

Because unless someone is willing to do that — to defend free speech in a principled, non-hypocritical way — the game theory says it’s just going to be a race to the bottom. And given the increasingly tenuous commitment to it in many corners of American society, free speech is going to lose out.

This is an understandable decision, given that it’s a survey of popular (student) opinion. In conducting a poll, you want to use language the respondents will understand and use themselves.

Another possibility is that the change is driven by the nature of speech in the age of the internet. Having a speaker come to a campus is no longer primarily about allowing people on campus to hear the speaker's ideas. If students want to hear the ideas of, say, Ben Shapiro, there are thousands of videos and recordings on YouTube and every podcasting service. Having him speak on your campus is arguably more about symbolism -- showing that a critical mass of students support him -- than about allowing students the chance to hear his ideas.

Students today may simply take for granted that everybody has all the access they need to all the ideas they could possibly want to be exposed to, and not perceive the shutting down of a speaker in the same way that earlier generations did.

Good article/analysis. I've taught free speech at UC Santa Cruz for almost two decades. For the past five years, there has, without question, been less support for free speech. Anecdotally, I think the pendulum is swinging back in response to book bans in Florida and overreach of cancel culture. Ultimately, however, what I tell people is that it isn't that the students don't support speech but that they don't believe in the institutions responsible for protecting speech (ie courts, universities and governments). If you see no role for precedent, then why would you support opposing speech -- a version of #5. If institutions are corrupt, then protecting the speech you hate, will not protect the speech you love.