Anatomy of a poker tournament

What it's like to get your hopes up of winning $1.1m and then have your dreams crushed, in one chart

There are two types of poker trips: Those where you play too much poker and those where you play too little. My recent trip to Las Vegas for the World Series of Poker fell deeply into the “too much” well and never recovered. For a stretch of 13 out of 14 nights,1 I either had an abbreviated dinner on a break from a poker tournament or ate something late at night after the tournament was over. (Don’t do this.)

I wound up cashing five events, which makes for some nice ink on my Hendon mob page — but I still just roughly broke even for this leg of the trip. (I’m hoping to make it back for a second stretch in July.) To a greater extent than I think even most professionals realize, tournament players are dependent on having some very big scores — we’re really talking about something in the six figures — to come out ahead for the year.

Near-misses soften the blow, but only a little. They can be fun, however, and the highlight of my trip was undoubtedly the $1,500 Monster Stack event, in which I finished in 32nd place out of 8,317 entrants for roughly $37,000. I’ve generally avoided these super-duper large weekend events at the WSOP: They’re crowded and slow, and you have to survive a long time to make real money from them.

Still, they offer a hard-to-resist upside proposition. My very crude guess is that there are something like 1,500 poker players who you wouldn’t want to see at your table at the WSOP — roughly 500 traveling tournament pros, another 500 highly competent online or cash game players who will sometimes play live tournaments, and then maybe 500 guys like me who were poker professionals at some point in their lives and are now mostly doing other things but still play a pretty solid game. So when you see a tournament with 8,317 entrants,2 it’s going to be good. Sure, most of the time, you’ll bust out and be $1,500 poorer for it. But if you make it to Day 3, when something like 5 percent of the field remains, you’ll essentially get to play a $25,000 tournament against mostly fish. That almost makes the pain worth it. Indeed, even by Day 4 of this event, when the $1.1m first prize felt very much in reach, the field was still mostly recreational players.

As it happened, I kept extremely detailed notes throughout the tournament, including basically every hand that I played. This is a lot of work and I only do it occasionally, but I’ll try to do it once or twice per trip. I work with a poker coach, and I’ve found that reviewing an entire start-to-finish tournament hand history works much better to detect problems then a “highlight reel” of hands. If you have leaks in your game that you aren’t aware of, you may never catch them with the highlight reel approach because you’ll never think to bring them to your coach’s attention.

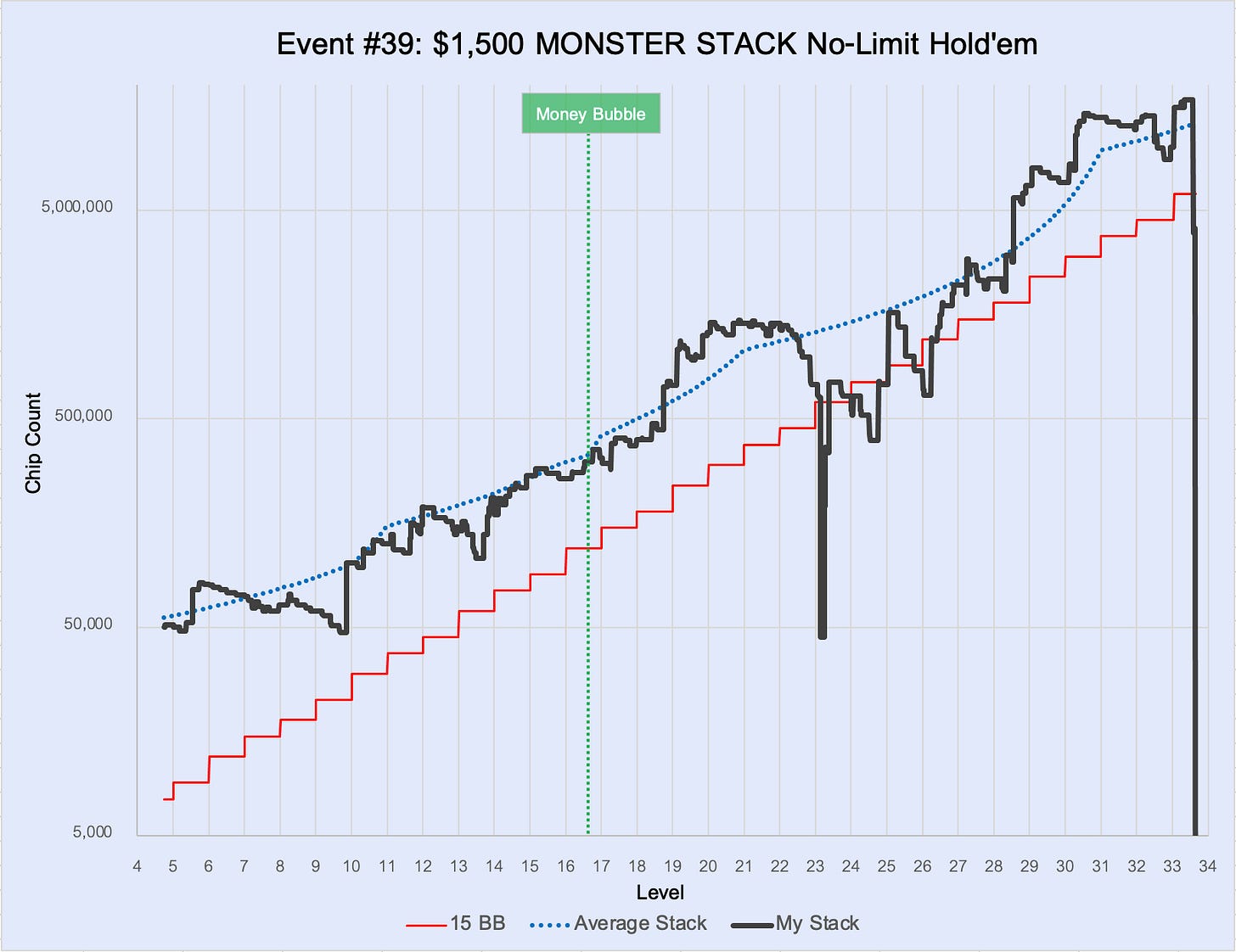

So — let’s do something with that data! Here’s a chart of how my stack fluctuated throughout four days of a very long tournament — although really more like three days, because my Day 4 was short once I ran AK into pocket aces.

That chart is — not very helpful, right? I mean, it gets the point across about how the stakes increase exponentially and how you’re playing for massive amounts of money by the time you get to Day 3. But the implication that nothing before that matters is totally wrong. I caught a big bluff late on Day 1 to double my stack, for instance. If I hadn’t done that, I probably wouldn’t have survived for nearly as long. You can think of a poker tournament as a coin-flipping contest: To win a tournament with 8,317 entrants, you basically have to win 13 coin flips in a row.3 (Two to the thirteenth power — 2^13 — is 8,196 or approximately 8,317.) Is the 13th flip intrinsically thousands of times more important than the first one? It certainly doesn’t feel that way when you’re playing. So let’s try this version instead, putting the Y-axis on a logarithmic scale.

Here, we can see the importance of big hands early in the tournament, including that big bluff-catch, which came just at the end of Level 9. We also see that something very funky happened on Level 23, early on Day 3. I raised AQo (ace-queen offsuit) on the button, the small blind shoved (went all-in) and I quickly called. “Oof, you’re way ahead”, he said when he saw my hand. I was expecting to see a worse ace — say, A4o. Instead, he somehow had five-deuce offsuit (52o). This was actually bad news. AQo only loses 25 percent of the time to A4o,4 but 35 percent of the time to 52o. And indeed, this opponent hit a two on the flop and I thought I was out of the tournament.

Except, it turned out that I’d started the hand with just a few more chips than him. I mean literally, only a few: I had 45,000 worth of chips left, and the big blind cost 40,000, leaving me with the proverbial chip-and-a-chair.

I hadn’t actaully studied how you’re supposed to play when you have just one blind left,5 but I decided to be patient. Finally, I got to the point where I was under the gun and about to pay the blinds again. I had to go with almost anything, peeled one card and saw it was a Q, and put my “stack” in. Another player raised so the pot was heads-up. I flipped my hand over, seeing my second card for the first time. I turned out to have two black queens — QQ! — which held up to beat AKo. Then I had two more double-ups in short succession to get back to having some kind of reasonable stack.

What else can we learn from the chart? I guess some of this is obvious, but it’s still worth keeping some of these tournament fundamentals in mind:

The blinds in a poker tournament increase exponentially — but that means the increase is linear if you put them on a logarithmic scale. (On the chart, the red line shows what a 15 big blind stack looks like, since that’s sort of the threshold where you can play any sort of “real” poker.) Basically, they go up by something like 1.25 or 1.3x every level.

The average stack decreases relative to the blinds over the course of the tournament — if it didn’t, the tournament would never end. So you have the luxury early on of being very patient. For instance, I basically got nothing going for most of Day 1 until the aforementioned bluff catch, and it didn’t really matter. By the latter levels, though, the average stack is fairly shallow and you need steady chip accumulation. Even doubling up only buys you about three levels relative to the rising blinds, for instance. You’ll need to win your share of medium-sized pots too, therefore, and that likely requires running some bluffs.

At the same time, players can be too obsessed with how their chip count fares against the field average. I had a below-average stack for more than 60 percent of the duration of the tournament, and yet I outlasted 99.6 percent of the field.

There’s an intrinsic asymmetry in tournaments in that you can lose the tournament in one hand but never win it in one hand.6

One last meta-tip: You’re going to have a much better chance of thriving in the late stages of a tournament if your brain thinks like the second (logarithmic) chart and not the first (linear) one. Yes, it’s kind of ridiculous that by the last hand I played in the tournament, a single big blind was worth 400,000 chips — almost a thousand times more than the 500-chip big blind in my first hand of the event.

But it’s still the same game with the same rules. I saw some players absolutely crack under the pressure, making big all-ins with very marginal hands as a way to avoid having to make tough decisions. If you find yourself in one of these spots for the first time, I get it — the nerves are going to be bad. The closer you can get to “ehh, fuck it, let’s just play poker”, the better off you’ll be. But if you can’t do that, you’ll probably want to be more deliberate in your decision making. It may even help to write your hands down, as I did. It’s a little harder to punt off a stack if you’ve committed to keeping a record of your decisions.

See you at the Main Event.

The lone exception was the night of the Golden Knights victory parade, where The Strip was basically impassable, though I’ll grant that being stuck in the Wynn is way more fun than being stuck in a Target or something.

Note that you could buy into the Monster Stack twice — if you busted Day 1a on Friday, you could come back for Day 1b on Saturday — so it may have been more like 5,000 or 6,000 distinct players. Still, there’s room for plenty of fish. You need to be more careful with this calculation with tournament that allow for several re-entries.

Although, a skilled player is essentially flipping coins with an edge — maybe they’re a 56/44 favorite on every flip or something like that. It’s hard to win 13 coin flips in a row with a 56/44 edge, but this matters more than you might think: a player with a 56% chance of winning each flip will win the tournament about four-and-a-half times as often as one who’s 50/50.

It also ties 6 percent of the time.

In principle, playing a hand as an extreme all-in short stack is very profitable — you’re guaranteed to see a showdown, and you can win 4x or more of your money back given the antes and the blinds — so solvers say you should play almost every hand when this shallow. My question is one of opportunity cost: Should I play a hand that has, say, 35 percent equity when I have several hands left to wait for something better? There were also payout jumps to consider: Surviving another 10 or 15 minutes might mean I made another $1,000 or so. If you’ve worked on this scenario, let me know in the comments!

Unless you’re heads-up and cover your opponent.

Responding to Footnote 5: I've done a bit of work on short stack tournament play, but it predates the big blind ante format (introduced to WSOP in 2018). It used to be the case that a substantial portion of your equity derived from the 'bottom' of your stack, motivating surprisingly tight play when not in the blinds. The big blind ante reduces and possibly eliminates that effect. When I get a chance I'll run some new simulations.

I know exactly what you mean about opportunity cost when you're very short-stacked...I guess you need to count how many orbits you have left (if any), considering the blinds, and what your odds are of drawing a better starting hand in your remaining hands. (Is this also a scenario where the Fundamental Theorem breaks down?). Probably any pocket pair or two face cards is a fist-pump shove. Probably suited connectors too. But face card and trash?