Fine, I'll run a regression analysis. But it won't make you happy.

State partisanship and COVID vaccination rates are strongly predictive of COVID death rates even once you account for age.

If you appreciate work like this, please consider a paid subscription! I plan to keep many posts free for the time being — especially when it comes to public disputes like this one. However, there are paywalled posts and other perks for paying subscribers.

One of my rules when I get in public debates as a statistician is: The simpler, the better. More or less, this is a version of Occam’s Razor. The more complications you introduce into an analysis, the more confounding variables that you attempt to control for, the more you expand researcher degrees of freedom — in other words, decision points by the analyst about how to run the numbers.

I don’t think it’s quite right to say these decisions are arbitrary. Ideally they’ll reflect a statistician’s judgment, experience and familiarity with the subject matter. Sometimes it’s absolutely necessary to control for confounders: otherwise you might wind up with ridiculous implications like that consuming ice cream causes drowning (summer weather is the obvious confounding variable). However, there are trade-offs when adding complications to your analysis. Although it’s possible to err in either direction, there’s a general tendency to overfit models.

My keep-it-simple attitude is also a stress response from years of experience arguing on the Internet. Any time you can make your point using simple counting statistics or other very straightforward methods, I consider that a win. People usually aren’t really interested in the intricacies beyond a certain point. Most of the time, what Scott Alexander calls “isolated demands for rigor” — there’s always some factor you haven’t accounted for — are just stepping stones on the road to confirmation bias.

So my aim is generally to focus on stylized facts that are true and robust. And to keep repeating them. I like simple (or simple-seeming) claims that — and I can’t emphasize this last part enough — I expect will hold up to scrutiny.

How do I know when a claim is robust? Well, sometimes I’m wrong. But, honestly, experience helps. I’m an American, for instance, and so I’m much more confident when making claims about how a statistic varies across American states than across Chinese provinces. And I have a lot of hands-on experience with making statistically-driven decisions and putting money behind them.

It also helps to have kicked the tires on the claim a bit. Maybe you have run the more complicated version of the analysis. Or even better, maybe you’ve run it several different ways. And maybe you’ve consulted other research on the subject. If you’ve done this, and you’re getting a consistent answer, your claim is probably robust. When this is the case, I don’t think it’s necessarily worth your time — when writing for a popular audience — to prepare the equivalent of a 20,000-word journal article detailing all your methods, full of Greek characters and dozens of footnotes.

In a post on Friday, I made two stylized claims that I believe to be true and robust:

Until vaccines became available, there was little difference in COVID death rates between blue states and red states.

After vaccines became available, there were clear differences, with red states having higher death rates, almost certainly as a result of lower vaccine uptake among Republicans.

This wasn’t intended as any sort of super-duper hot take, and I pared the post down to avoid having too much of an attack surface. Nevertheless, it quickly became the most commented-upon post in the (short) history of this publication. The comments here were fairly civil, especially at first. (I really appreciate that, everyone.) Externally, though, these claims were more controversial. Here for instance, was Martin Kulldorff on Twitter/X:

Children with large feet are better at math, but not after adjusting for age

Older people have >1000 time higher Covid mortality, and state average age differ by >10 years, so unadjusted state comparisons are misleading

@NateSilver538 may wish to consult a statistician

Kulldorff is not just some casual; he is a Professor of Medicine at Harvard.1 He is also one of the lead authors of the Great Barrington Declaration (GBD), an October 2020 anti-lockdown statement signed by a large number of scientists and medical professionals. “Those who are not vulnerable should immediately be allowed to resume life as normal,” the statement read.

If you don’t know my history with COVID policy2 and just think of me as Some Nerd Who Thinks The Vaccines Were Good, you’re probably expecting me to make fun of the GBD, which has been the subject of a lot of critical commentary. But actually, I mostly agree with it. I think its claims about focused protection and herd immunity were too optimistic. But I think it was directionally right — that by October 2020, the evidence was on the side of the costs of these measures outweighing the benefits. I also think efforts to suppress discussion of the GBD and to label it as “misinformation” were bullshit.

Of course, the first of the two claims I made in Friday’s post supported this very point. Before the introduction of vaccines, it isn’t clear that the other things we were doing to stop COVID were really working well at all — and they were very costly.

But on Twitter, I guess, you’ll rarely get credit for half-agreeing with someone. So Kulldorff took issue with my latter claim — that red states had higher death rates once vaccines became available — arguing that it was “meaningless” because I hadn’t adjusted for age.

State partisanship is strongly related to COVID death rates, even once you control for age

Kulldorff’s argument is unsound. Age does explain some of the differences in COVID death rates between states. Certainly, COVID is much, much more deadly for older people, to an extent the media probably didn’t emphasize enough. But, this is almost entirely orthogonal to state partisanship — and even more so to vaccination rates.

As a quick aside, as someone who’s spent a lot of time looking at how behavioral and attitudinal data varies across American states, I think you should generally be suspicious when people attribute a lot of the differences to age. States don’t vary that much in age.3 It isn’t like variables such as racial or religious prevalence, where the deltas can be much larger (e.g. Utah has 100x the Mormon population of some other states). Age also doesn’t really pass an eyeball test as explaining the differences between states in COVID death rates, as I pointed out to Kulldorff on Twitter:

The four oldest states are West Virginia (very red), Florida (pretty red), Maine (pretty blue) and Vermont (very blue). What are their COVID death rates (per 1M population) since Feb. 1, 2021 (i.e. post-vaccine?):

West Virginia: 3454

Florida: 2992

Maine: 1881

Vermont: 1210

These states all have the ~same elderly population, and yet there are huge variations in COVID death rates that line up 1:1 with partisan differences in vaccine uptake.

But OK, fine, let’s do this properly. Let’s run a regression analysis, which is a technique to decompose the effect of different variables. First, as a baseline, let’s run a simple, one-variable regression to back up my claim that state partisanship predicts COVID death rates.

In this specification, covid_deaths_late is the number of COVID deaths per 1M residents (source) since Feb. 1, 2021 (I chose this date in Friday’s post since it approximates when COVID vaccines became widely available to vulnerable groups.) Meanwhile, biden is Joe Biden’s margin of victory or defeat against Donald Trump in 2020 (source). You can see that biden is very strongly and statistically significantly predictive of COVID death rates since 2/1/2021. The larger Biden’s margin of victory, the lower the COVID death rate. Note, again, that this wasn’t true in the early days of COVID; it’s only been true since the vaccines became available.

OK, now let’s add age to the mix, measured by the share of the state population that is aged 65 or older (source). This variable is designated as senior in the analysis.

Older states have had more COVID deaths since 2/1/2021 and the difference is statistically significant. However, this doesn’t affect the finding about state partisanship. In fact, state partisanship is just as predictive even once you control for age. As you can see, both the coefficient on biden and its statistical significance are essentially unchanged once you add age to the equation.

The differences in state death rates are very likely because of differences in vaccine uptake

Just to be clear, I don’t mean to imply that COVID is intrinsically more likely to target Republicans or anything like that. Rather, my claim is that COVID is considerably more deadly in people who haven’t been vaccinated, and since Republicans are less likely to be vaccinated than Democrats, state partisanship serves as a proxy for this.

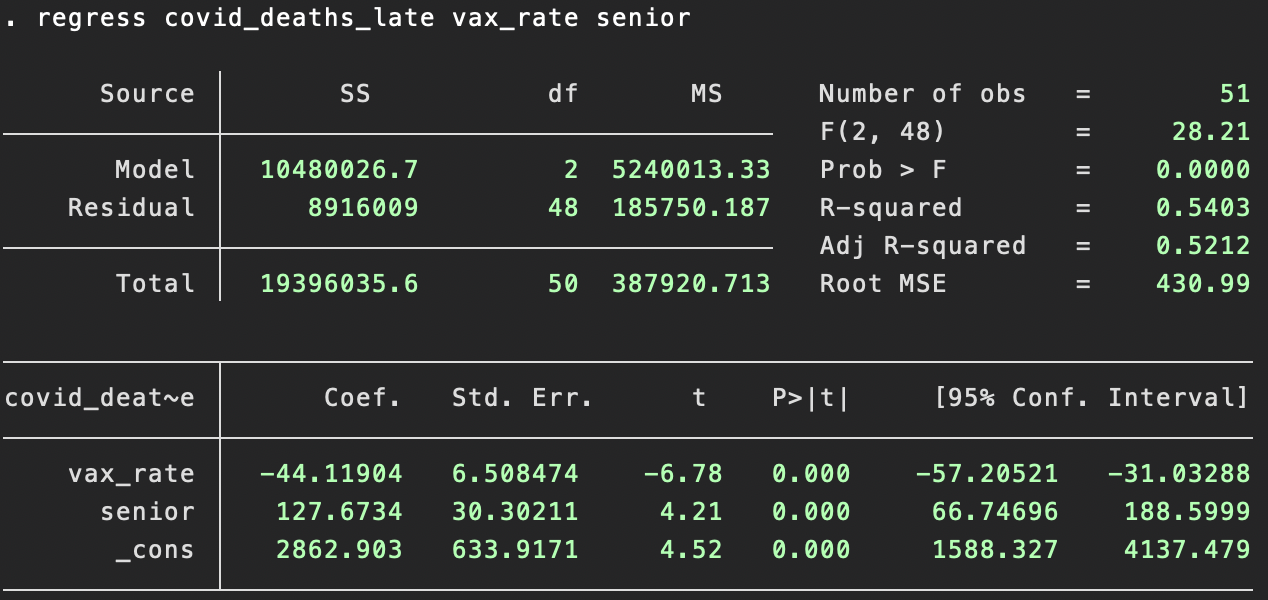

Indeed, we can look at vaccination directly. In our next build of the model, vax_rate will refer to the share of a state’s residents that are “fully vaccinated”4 (source). When you include vax_rate, it dominates biden. That is to say, vaccination rates themselves are considerably more predictive of COVID death rates than state partisanship as an approximation for them.

Finally, just to clean things up, we can drop biden from the analysis; it has essentially no effect once you control for age and vaccination rates. Despite a fair amount of stochasticity in how COVID spreads — particular variants can take hold in different parts of the country in ways that seem difficult to predict — age and vaccination rates alone explain more than half of the variation in COVID death rates between states since Feb. 2021.

Is this going to satisfy anyone? Hopefully it’s edifying to Silver Bulletin readers. As for Kulldorff and other Twitter critics, I have my doubts, I guess. There are always other things you can bring up. What about comorbidities — don’t those vary across states? (They do.) Are all states counting COVID deaths in the same way? (Probably not.) What about the first claim in Friday’s post — is it really so clear that NPIs had no effect in the pre-vaccine era? (I actually think this claim is less robust than the second, apparently more controversial one.)

None of these are unreasonable questions. But the point of a robust claim is that it holds up to minor, medium-sized and often even fairly large objections. For instance, if states had a more standardized way of accounting for COVID deaths, it might mean that vaccination rates were even more statistically predictive of COVID death rates. Or it might not. But I wouldn’t expect it knock the claim into a different category, i.e. to take it from “clearly true” to “dubiously true” or “probably false”.

Writers like Scott Alexander will sometimes go to very great lengths — literally tens of thousands of words — to parse particular statistical claims when Someone Is Wrong On The Internet. I greatly admire this, though I’m more cynical about the utility of it. I mostly don’t think that people are arguing to be truth-seeking in the first place — certainly not on Twitter, and certainly not about COVID. But I’m hoping to have a little bit more tolerance for back-and-forth argumentation here at Silver Bulletin. Don’t forget to tune in next week, when instead of people arguing with me about vaccines, they’ll yell at me about RFK Jr..

Although, Kulldorff’s Twitter bio says he is currently “on leave” there.

I’ve taken a lot of shit from the left over the years for arguing that these measures failed a cost-benefit test.

As measured by their senior population, all but nine states are within a narrow band, with greater than 15 percent of their populations but less than 20 percent of their populations being senior citizens (age 65+).

That is, who got two initial doses of Pfizer or Modena or one initial dose of Johnson & Johnson — no booster doses required.

Death rates diverged at the point in time at which the vax was introduced. Isn’t that itself strong evidence? Unlikely that the confounders changed substantially at that exact time.

I find this analysis all pretty compelling. Thanks for the follow up, Nate. One item that does catch my eye, though, is this:

>>Are all states counting COVID deaths in the same way? (Probably not.)<<

It probably would be interesting to look at excess mortality instead of COVID deaths. I do recall seeing nation-to-nation comparisons that appears to differ quite a bit when using the former rather than the latter. But I haven't looked into whether the US (or individual states) compile state-level excess mortality numbers.